Mexican CIE Turned Live Entertainment into an Empire and Ticket Gold

From Mexico City to Formula 1 weekends, CIE built OCESA into Latin America’s ticket machine. But behind sold-out Bad Bunny nights and Taylor Swift screams, debt scares, pandemics, and foreign buyouts reveal the price of spectacle in Mexico.

The Crowd That Finally Became a Market

On October 27, 2024, Autódromo Hermanos Rodríguez shook as Carlos Sainz won the Formula 1 Mexico City Grand Prix. It looked frictionless. For Mexico City, that ease is the point: mass gatherings here were once seen as trouble.

Corporación Interamericana de Entretenimiento (CIE), founded in 1990 as Operadora de Centro de Espectáculos S.A. (OCESA), was a major reason for that change. By ticket sales, it ranks among the world’s top four entertainment companies. CIE doesn’t just book acts—it controls the infrastructure: venues, ticketing, advertising, and food sales, turning logistics into leverage.

This feature is adapted from the original Americas Quarterly report and interviews by Cyntia Barrera Díazo. Her reporting recalls the years when big concerts tested the country’s nerves. In 1989, with no Mexico City venue willing to host him, Rod Stewart performed in Querétaro and drew more than 50,000 fans; security collapsed, and police used tear gas. The audience was ready long before the system was.

Paul McCartney And the Stadium Built on Improvisation

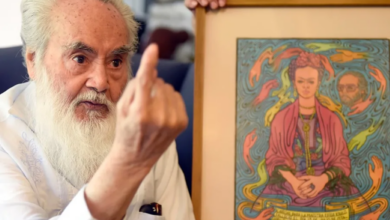

Alejandro Soberón Kuri, CIE’s founder, helped build that system show by show. In 1991, the company’s first two concerts featured INXS at Palacio de los Deportes, built for the 1968 Olympics and seating more than 15,000—an early test of whether big crowds could be managed in Mexico City.

In 1993, CIE booked Paul McCartney and ran into a harsh reality: the city lacked a suitable venue to meet the demand. Estadio Azteca, home to two FIFA World Cups, was the only place big enough, but Televisa refused to lease it. Following advice from tour promoter Barrie Marshall, Soberón and his team built a workaround on an auto racing track, assembling metal seating structures. Around 120,000 tickets were sold for McCartney’s first two shows in Mexico.

Weeks later, Madonna brought her Girlie Show tour to the same venue despite efforts to censor it for sexual and religious content. She chose Mexico after hearing from McCartney about his show—a reminder that a country’s touring reputation spreads through artists, not brochures.

Then December 1994 arrived. The Tequila Crisis slashed the peso’s value by over half, almost overnight, and money set aside to pay the Rolling Stones and dozens of other acts evaporated in days.

From Ipo Rescue to Live Nation Majority Rule

To survive and keep growing, CIE went public in December 1995. Expansion followed, and in 2002, Televisa invested $107 million to acquire a 40% stake in OCESA Entretenimiento. But debt accumulated. By December 2009, CIE announced a $400 million restructuring plan and began shedding non-core assets, refocusing on concerts, theater, and festivals.

The cultural payoff is now unmistakable. Since 2015, CIE has positioned the Formula 1 Mexico City Grand Prix as a destination event, helping make Mexico a reliable stop for stadium tours. When Taylor Swift brought her Eras Tour to Foro Sol in 2023, she wrote on Instagram: “After years of wanting to play in Mexico City, just got to play 4 of the most unforgettable shows for the most beautiful and generous fans.”

The business side remains harder to romanticize. PwC labeled Mexico’s entertainment and media sectors “fast-growing” in July, projecting a 6.26% compound annual growth rate that could reach $33.5 billion by 2029. CIE operates 14 venues in Mexico City, plus one in Monterrey and two in Guadalajara, with a capacity exceeding 312,000 visitors. Yet its revenue was about $226 million last year, a 3.9% decline from 2023.

In 2019, Live Nation offered about $400 million to acquire a 51% stake in OCESA Entretenimiento, including Televisa’s share. COVID-19 froze the industry and the deal; CIE even turned a convention center into a temporary hospital in a country that recorded over 600,000 deaths. After renegotiations failed, Live Nation terminated the purchase, and arbitration followed, until a new agreement brought the acquisition to completion in late 2021.

Earlier this year, Live Nation increased its stake to 75%. CIE declined to grant an interview with CEO Alejandro Soberón Kuri, citing scheduling constraints. In a June report, HR Ratings analysts projected 2% annual revenue growth between 2025 and 2028, driven by the normalization of special events and the expansion of the Formula 1 Mexico City Grand Prix.

The Mexico City Grand Prix is confirmed through 2028, and CIE aims to connect the event more closely with Day of the Dead. The real question: who controls the celebration?

Also Read: Panama Geisha World’s Most Expensive Coffee Braces for Climate Swings