Mexico And Michoacán Reckoning Test Sheinbaum As Cartels Tax Avocados

In Mexico, Claudia Sheinbaum inherits Michoacán’s orchard wars, where cartels treat avocados and lemons like cash registers. After killings in Uruapan on November 2, her promised Plan Michoacán confronts a question: can the state return to villages before winter arrives?

Day of the Dead, Day of Debt

The marigolds were already laid out in Uruapan when the celebration turned into a crime scene. In less than two weeks, two men who challenged cartel power were killed: Bernardo Bravo, a lemon growers’ leader, and Mayor Carlos Manzo, shot during Day of the Dead on November 2. In reporting and interviews for Americas Quarterly, author Denise Dresser says both warned that criminal groups had burrowed into agricultural supply chains, extorting producers while authorities looked the other way.

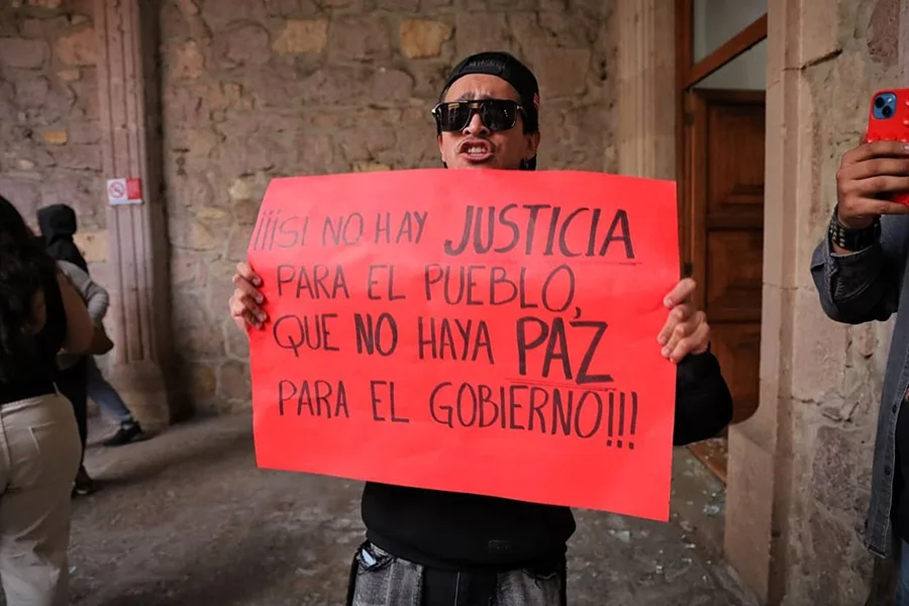

Demonstrations surged in Uruapan and in Morelia, because the killings felt like proof of capture. Michoacán exports lemons and avocados to the United States; that prosperity makes farms visible targets. In Dresser’s account, growers describe a criminal “tax,” coerced price collusion, and orders about when to harvest and where to sell,a tollbooth economy built on fear that travels with the fruit. In towns built around orchards, that “tax” lands like drought: slow, exhausting, and politically corrosive.

The war on drugs that never left

Since the mid-2000s, the struggle in Michoacán has been about more than drug routes: extortion, product control, and governance capture. In 2007, then-governor Lázaro Cárdenas Batel, today head of Sheinbaum’s Office of the Presidency, asked President Felipe Calderón for federal assistance. The response helped inaugurate the “War on Drugs” and made Michoacán an early laboratory for militarized internal security. Instead of reducing violence, it helped trigger a wave of escalation.

Public figures trace the escalation in numbers. Under Calderón (2006–2012), organized crime-related murders surged; in 2010, there were 15,273, up from 9,616 in 2009. Under Enrique Peña Nieto (2012–2018), intentional homicides surpassed 104,000, compared with about 102,859 under Calderón. Between 2019 and 2021, under Andrés Manuel López Obrador, Mexico recorded about 109,059 murders. Those figures map a cycle: military pressure splinters organizations, competition multiplies, and violence seeps into the legal economy.

Studies in the Journal of Latin American Studies and Latin American Research Review examine “criminal governance,” when armed groups extract rents from legal economies while disputing political authority. In Michoacán, Dresser reports the Cártel Jalisco Nueva Generación (CJNG), networks like Los Blancos de Troya, and remnants of La Familia Michoacana have pushed into agribusiness extortion. The Justice in Mexico project, covering 2000–2017, documented at least 150 mayors and local officials killed by 2017, with peaks of 20 in 2010 and an average near 10 per year earlier. Mayors are targeted because their office threatens territorial control, extortion profits, and the façade of order cartels sell.

Plan Michoacán and the price of honesty

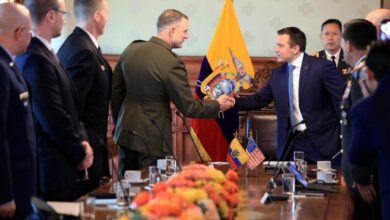

After Manzo’s assassination, President Claudia Sheinbaum condemned the killing as “vile,” pledged “zero impunity” and “full justice,” and convened her security cabinet, according to Americas Quarterly and Denise Dresser. She announced Plan Michoacán, promising federal deployments, prosecutor coordination, intelligence sharing, and social programs. Dresser notes the outline is vague and under-budgeted,and awkward, since Morena has governed Michoacán for four years. Sheinbaum’s first instinct was to blame the past, not her party’s stewardship of the present. She insists this is not militarization, even as federal force remains the centerpiece.

Sheinbaum says stronger intelligence and coordination,led by Security Secretary Omar García Harfuch,can reduce violence, and she points to national declines in homicide. But Dresser warns in Americas Quarterly that averages hide a split map: Mexico City can improve while Michoacán, Guerrero, Chiapas, and Sinaloa slide toward “no-man’s lands.” In those zones, businesses budget for extortion the way they budget for fertilizer and fuel today. With President Donald Trump pressing Mexico for results, the room for half-measures narrows.

For farmers, the stakes are safety on the road to the packinghouse and a government that arrives before the funeral. If Plan Michoacán does not dismantle extortion and collusion, it becomes another containment ritual. A turning point would mean protecting local leaders, rebuilding civilian policing, and funding reforms transparently. With President Donald Trump watching, Mexico cannot afford another slogan. In Michoacán, sovereignty is harvested,or lost,one crate at a time.

Also Read: Panama Beckons Retirees While Latin America Questions Who Truly Benefits