Cuba’s Unseen Crisis: As Poverty Deepens, the Government Renames It and Struggles to Respond

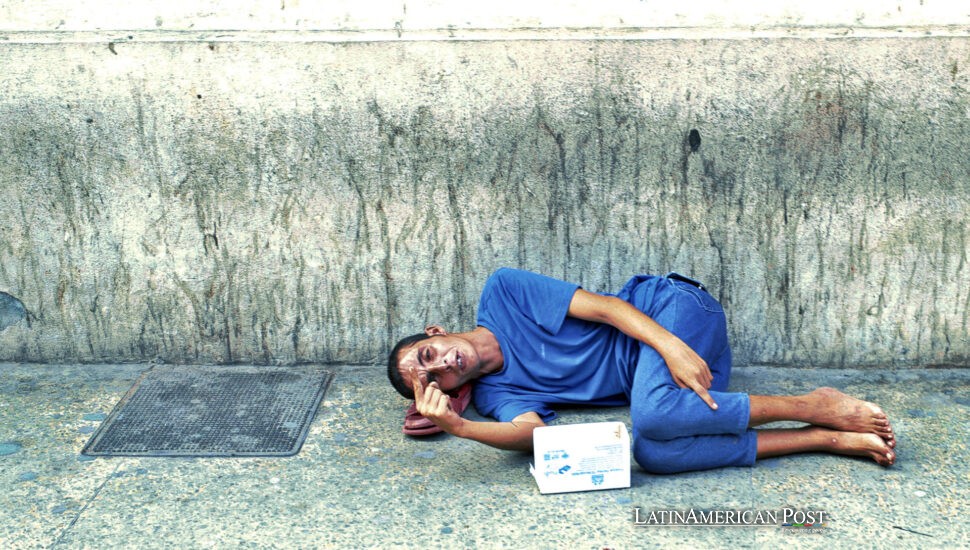

In Havana’s backstreets, pensioners dig through garbage while officials debate terms like “wandering conduct.” With eggs now costing more than a monthly pension, Cuba’s growing poverty crisis isn’t just about survival—it’s about whether the government is willing to name it.

Hunger in a Revolution That Promised Equality

Just after noon on Havana’s busy promenade, José Fernández, a pensioner in his seventies, wipes sweat from his face and plunges his arm into a dumpster. What he finds—a stale roll, a crumpled box of juice—he saves for dinner.

His pension is 1,674 Cuban pesos, equivalent to approximately $13 at the official exchange rate. A carton of thirty eggs costs twice that.

A few blocks away, José Luis Balsinder, 56, arrives after walking nearly fifty kilometers from Guanajay, a rural town where pickings are worse. He used to guard a warehouse for 2,500 pesos a month—roughly $20—but inflation erased its value. Now, he searches for leftovers outside Miramar’s luxury homes, where imported wine and foreign steaks fill menus that feel like fiction to him.

“If there’s nothing here,” he says, “imagine what it’s like back home.”

Their reality unfolds beneath billboards celebrating Cuba’s revolution, which once promised “no one would be abandoned.” But in today’s Havana, survival hinges on luck, long walks, and whatever is left behind by tourists.

Words Meant to Soften Reality, and a Minister’s Fall

Cuba’s government doesn’t call José or Balsinder homeless. It refers to them as “persons with wandering conduct.”

That euphemism ignited national outrage when Labor Minister Marta Elena Feitó used it before parliament, insisting “there are no beggars in Cuba.” She claimed some people “disguise themselves” to avoid taxes. Legislators applauded.

The applause didn’t last.

President Miguel Díaz-Canel rebuked Feitó the very next day, warning that the revolution should never “hide our problems.” By nightfall, she had resigned.

But the language persists. Between 2014 and 2023, government statistics recorded just 3,690 homeless people, mostly older men. Economists, however, call the number a vast understatement.

Prime Minister Manuel Marrero later admitted that over 310,000 Cubans—about 3 percent of the population—live in “vulnerable situations.” However, critics argue that labeling it “vulnerability” implies something that might happen, rather than what already exists.

“You can’t fix what you won’t name,” says economist Tamarys Bahamonde, in an interview with EFE. “And if poverty isn’t officially recognized, it isn’t addressed.”

Inflation, Job Losses, and a Vanishing Middle

Marrero promises help: beginning in September, the minimum pension will double to 3,056 pesos—about $25. That’s the cost of a single carton of eggs.

And it’s not enough.

Independent economist Omar Everleny calculates that by the end of 2023, a two-person household would need 24,351 pesos to cover its monthly food expenses. That figure doesn’t include clothing, soap, transportation, or mobile data—all of which have soared in price.

The average state salary? 5,839 pesos—less than $50 a month.

Professionals, including teachers and doctors, are increasingly turning to side hustles, such as selling pastries from home, driving tourists, or renting rooms on Airbnb. Others have left the country altogether.

The closure of Cuba’s largest copper mine last year, following a court order, added to the strain. Six thousand jobs vanished, along with forty thousand support roles, sending even more workers into the informal economy, which is now estimated to include nearly half of the national labor force.

Officially, Cuba doesn’t have mass unemployment. Unofficially, more people are unemployed than ever before—they just aren’t being counted.

Naming the Crisis Is the First Step Toward Solving It

Bahamonde believes the Cuban government’s refusal to say “poverty” out loud is a policy failure in itself.

“Calling someone ‘vulnerable’ is polite,” she says. “But it shifts the blame. It makes hunger sound like bad luck.”

Others echo her warning. Cuba’s five-year economic downturn, driven by the pandemic, the loss of Venezuelan subsidies, and U.S. sanctions, has left grocery stores barren, power cuts routine, and medicine shelves empty. The safety net is fraying—if not already broken.

Meanwhile, data releases are sporadic, and state media rarely publish in-depth reports on the topic of inequality. When asked directly, government spokespeople cite “transformation goals” and “social commitments”—but rarely specifics.

For Cubans like Fernández and Balsinder, such language feels hollow. On a recent afternoon, Fernández scooped up a half-eaten slice of pizza left on a café table, unfazed by passing tourists. In Guanajay, Balsinder’s neighbors wait for whatever food scraps he might return with.

They don’t need studies or speeches. They need bread that doesn’t cost half a week’s pension, and a name for what they’re living through.

Back in Havana, government officials have promised that the new labor minister will “restore dignity.” However, without clear terms—and explicit action—it’s unclear whether that dignity will extend beyond the podium and into the streets.

For now, hunger remains stubbornly unimpressed by euphemism. The price of eggs keeps climbing. And in dumpsters, across plazas and behind shuttered storefronts, Cubans like Fernández and Balsinder keep searching—for food, for fairness, and for a future.

Also Read: Panama’s Uneven Comeback: Behind Growth Headlines, a Job Crisis Spreads from Ports to Banana Fields

Credits: Reporting and interviews by EFE with José Fernández, José Luis Balsinder, Omar Everleny, Tamarys Bahamonde, and Marta Ponce; economic data from Cuba’s National Office of Statistics and Information; historical context from independent labor and poverty research conducted in Havana and Guanajay.