Latin American Workers Keep Albania’s Tourism Afloat Amid a Shrinking Workforce

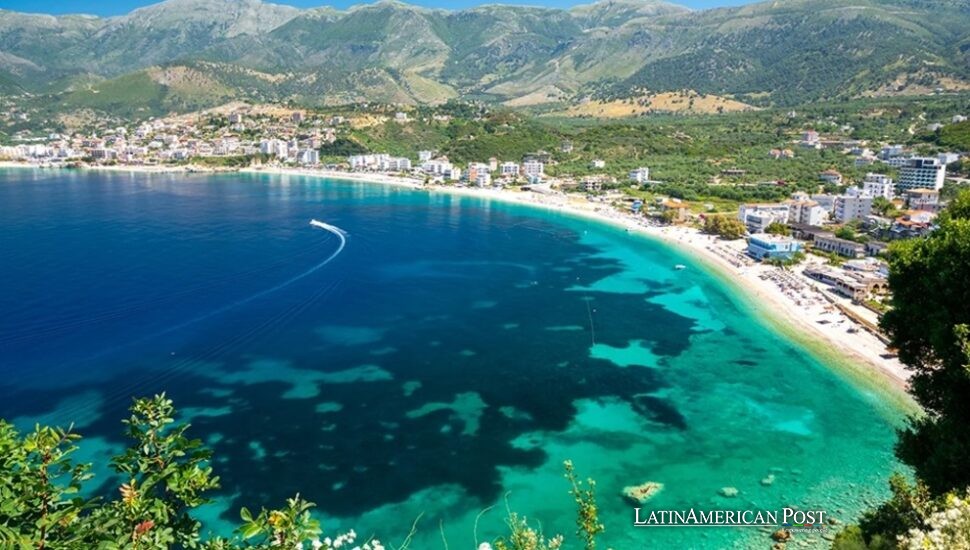

From the beaches of Vlora to the crowded promenades of Saranda, the sound of the waves now mingles with accents from thousands of miles away. As Albania’s visitor numbers soar, its hotels and resorts are leaning on a new labor force from Latin America—filling jobs the country no longer has enough people to staff.

Beaches Learn a New Accent

On Albania’s southern riviera, where turquoise water meets pebble shores, the summer rush is impossible to miss—and impossible to manage without outside help. Hotel receptions, beach bars, and lifeguard posts that once drew workers from nearby towns are now staffed by newcomers from Venezuela, Colombia, and beyond.

“The coastal zone is attracting more and more Latin Americans who find work in hospitality,” Klevis, a restaurant owner in Shëngjin, told EFE. His seafood place, far from the southern resorts, keeps two Filipino employees on staff year-round because he can’t find local replacements. The problem isn’t confined to one town. Across Albania’s coast, new hotels and beach clubs keep opening—part of a tourism surge that lifted arrivals from 3.8 million in 2014 to nearly 12 million in 2024—but “help wanted” signs now hang just as prominently as menus.

A Boom Meets a Demographic Bust

Albania’s rapid rise as a low-cost Mediterranean destination has collided head-on with its shrinking population. In the past decade, emigration has reduced the number of residents from 2.9 million to about 2.4 million. Many of those leaving are young and educated—the very people the hospitality industry needs most in peak season.

“We have begun hiring workers from Latin America, since they can enter Albania without a visa,” explained Rrahman Kasa, president of the Albanian Tourism Union, in comments to EFE via Tirana’s A2 television. Employers, he added, are finding that wages in Albania—€650 to €1,000 a month in tourism—are competitive for Latin American workers, especially when paired with the chance to live on the coast for the season.

The trend is measurable. Official data shows the number of foreign employees grew from 9,825 in 2023 to around 13,000 in 2024, with another 15–20% jump expected by mid-2025. Even so, foreigners make up less than 1% of the total population, meaning the influx is still modest compared to other European destinations.

Visas, Wages, and a New Pipeline

For business owners, these numbers translate into familiar faces. Klevis smiles when talking about Antonio, his head cook, and Roberto, his assistant—both of whom return each summer. “In winter they work in Tirana, but in summer they come back here because we pay higher wages,” he told EFE. That seasonal rhythm—capital city in the off months, coast in the high season—has become a lifeline for employers who can’t afford to start from scratch every June.

Visa-free entry for many Latin Americans has made recruitment easier. Word of mouth spreads quickly, aided by social media job ads that now cross continents. The shift began with hiring from Asia—Philippines, India, Nepal, Bangladesh—to cover kitchen and housekeeping jobs. As the labor crunch deepened, operators reached farther afield. Latin American workers, often experienced in global hospitality and fluent in multiple languages, fit easily into guest-facing roles that cater to Albania’s mix of Western European visitors and diaspora travelers.

EFE

Can the Model Last?

The State Employment Service says more than 6,000 tourism vacancies remain unfilled nationwide. “No sector feels this shortage more than tourism,” director Gertiola Çepani told EFE. According to the news portal Telegrafi, foreign workers currently fill only about 10% of open roles. Tourism expert Feriolt Ozuni warns the industry needs 35% more staff to meet demand—without them, service quality could slip just as Albania is gaining global attention.

The labor shortage isn’t unique to tourism. Construction and manufacturing are also competing for the same shrinking pool of workers, driving pressure on wages and training systems. Employers argue that better pay, faster hiring procedures for foreign staff, and modern vocational programs could help keep more Albanians in the sector.

There are advantages to build on. The coastal salary range, while low by Western European standards, stretches further in Albania; the high season grows longer each year; and returning foreign workers create a steady, trained labor pool. But the math is stark: without deeper investment in people—both domestic and foreign—the tourism boom could plateau, leaving the economy more vulnerable to seasonal shocks.

For now, the coast feels buoyant. Sun loungers line the beaches in neat rows, languages blend in the sea breeze, and the lunch rush moves with the practiced rhythm of cooks, servers, and lifeguards from both sides of the Atlantic. In one kitchen, Antonio plates a sea bream for the terrace; at the front desk, a receptionist shifts from Italian to Spanish to English without missing a beat; on the sand, a lifeguard’s whistle cuts through the cicadas.

Also Read: Peru’s Largest Solar Plant Shines for the Nation but Leaves Its Indigenous Neighbors in the Dark

Albania’s summer economy is still finding a way forward, carried in part by the workers who have come halfway around the world to keep the season alive. And for many of them, the road from Latin America now ends exactly where the Adriatic meets the shore.