Mexico City at War with Itself: The Anti-Gentrification Uprising Tearing Through Its Streets

A storm is gathering in Mexico City’s prettiest neighborhoods, where rent hikes, tech nomads, and Airbnb profits collide with the lives of locals who’ve called these cobbled streets home for generations—and now march to keep it that way.

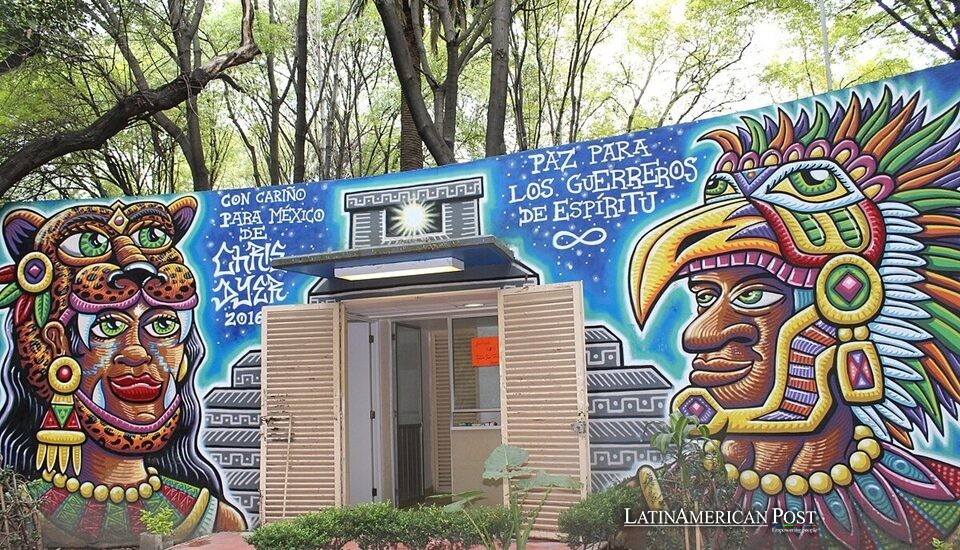

The Revolt Behind the Murals

On sunny afternoons, Roma and Condesa gleam with a curated charm: baristas perfecting matcha, murals worthy of gallery walls, and sidewalks filled with yoga mats, lapdogs, and foreign tongues. But, as reported by Wired, beneath the polished veneer, something’s cracking. For every artisanal café that opens, another family packs up, priced out by rent hikes no working-class salary can keep up with.

Activists estimate that more than 20,000 families a year are being forced to leave the capital—not because they want to, but because they can no longer afford to stay. And now, as Mexico City becomes a global hotspot for remote workers, the social fabric is fraying faster than ever.

The city is bracing for yet another confrontation. Protesters—many of them lifelong residents—have already taken to the streets three times this July. Their signs warn of an “imperial eviction” powered by U.S. dollars and short-term rental platforms. Another march is scheduled for July 26, this time from the Hemiciclo to Juárez, a symbolic route that authorities call a calculated provocation.

At the July 20 rally, hundreds from Tlalpan’s Fuentes Brotantes neighborhood waved cardboard replicas of their rent bills—painted over in bright red, each one doubled in cost since 2020. In Roma and Doctores, lifelong tenants chanted past their own former homes, now listed for $ 200 a night on Airbnb. The Secretary of Government, César Cravioto, acknowledged the protesters’ concerns, but warned of “agitators bent on vandalism” after earlier events saw storefronts smashed.

Still, the message is clear: these aren’t just marches—they’re eviction notices, thrown back at the system.

A Mayor’s Last Stand

Cornered by mounting unrest, Mayor Clara Brugada responded on July 16 with what she calls the city’s boldest housing push in a generation: a 14-point initiative named “Bando 1.” It’s more than a press release—it’s a line in the sand.

At its heart is a series of public forums set to begin July 28 in Roma, Condesa, Juárez, Escandón, and San Miguel Chapultepec—neighborhoods at the epicenter of the crisis. These meetings will not only include officials but also tenants, developers, researchers, cultural collectives, and small business owners. Their job? To design a new Master Urban Development Plan grounded in four principles: the right to remain, community over speculation, defense of neighborhood identity, and a city built for people—not investors.

Brugada pledged that by September, the city will produce concrete policy proposals, including a Fair and Affordable Rents Law that pegs rent increases to inflation in high-pressure zones. There’s also talk of an independent Tenants’ Ombudsman and a crackdown on short-stay listings that distort local housing markets.

Alejandro Encinas, the city’s Secretary of Urban Planning, said they’re mapping “problem zones” based on rising land values and a surge in vacation rentals. It’s the kind of language that makes landlords nervous—and tenants cautiously hopeful.

Who Was Forced to Leave?

But before laws can change, the city wants the numbers. How many people, exactly, have been displaced? And where did they go?

Brugada has ordered a displacement census to be conducted within the next two weeks. The Housing Secretariat has been tasked with presenting a detection strategy—a tall order in a city where informal renting is as common as tacos al pastor. Yet the goal is to prioritize those who were pushed out during the remote-work boom, offering subsidies for their return and accelerating the issuance of permits for affordable housing construction.

The short-term plan includes aid for family-run businesses struggling with rising rents and simplified regulations for affordable housing developers. Brugada insists the reforms will materialize fast: “In four months, we will have the legal tools to confront gentrification decisively.”

Landlords’ groups aren’t so sure. They’re already warning of lawsuits, saying that strict rent controls could reduce supply, discourage investment, and ultimately hurt tenants—the very people the policies aim to protect.

Wikimedia Commons

Gringos, Ghost Kitchens, and Geopolitics

What began as a dispute over rent has quickly evolved into something larger: a cultural battle with geopolitical undertones. Anti-American slogans like “Gringo go home” now appear beside calls for rent justice. Some signs urge newcomers to “pay taxes, learn Spanish.”

The U.S. government didn’t help its case. A tweet from the Department of Homeland Security encouraged undocumented migrants to use the CBP One app “to facilitate their departure” if they wished to protest in Mexico—an eyebrow-raising jab that drew fire from President Claudia Sheinbaum. “Inclusion,” she replied, “not mere tolerance, is the answer.”

The irony doesn’t escape observers. Mexico routinely condemns harsh immigration crackdowns by the U.S.—so what happens when the roles reverse? When are foreign residents under fire? The city’s moral compass now faces a stress test.

But protest leaders say the rage isn’t about nationality—it’s about behavior. Eduardo Alanís of the Frente Anti Gentrificación CDMX told Wired that the issue is speculative profit, not passports. “Everyone is welcome—if they respect our right to stay,” he said, seated beneath the jacaranda blossoms of Plaza Río de Janeiro.

Also Read: Uruguay Builds a Housing Revolution One Brick—and One Neighbor—at a Time

As another protest nears and public forums open across the city, Mexico City teeters between two identities: global showcase or local sanctuary. The coming months may determine whether the capital reinvents itself—or just sells itself off, one square foot at a time.