Bolivia's Young Dreamers Command A Magical Miniature Festival

On a Thursday morning in La Paz, children dressed in bright traditional outfits enlivened the Ch’iti Feria with laughter and crafts. Their presence ensured that the treasured Alasita celebration, an age-old gathering of miniatures and dreams, remained relevant.

A Child-Centered Celebration in La Paz

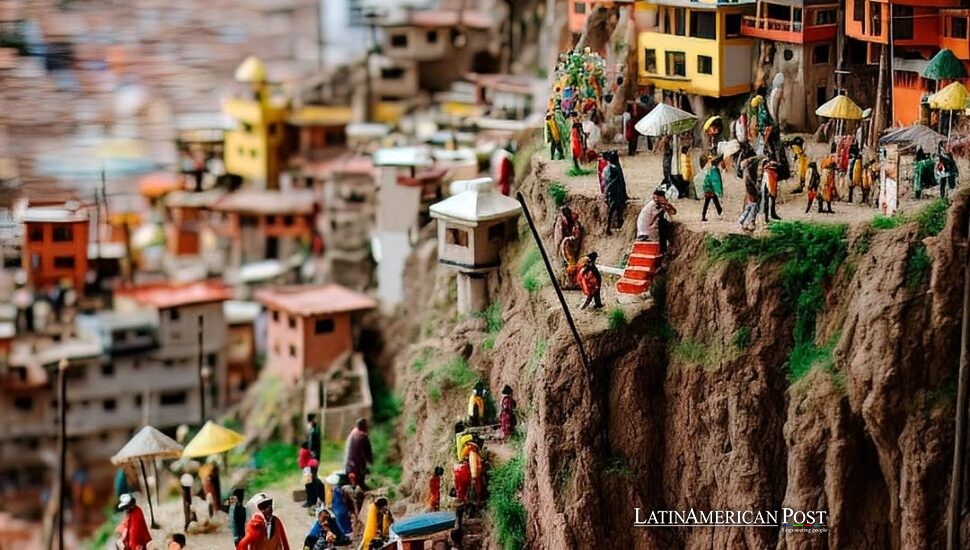

A lively bustle took hold of the streets in the early hours of the Ch’iti Feria, a special segment within Bolivia’s broader Alasita festival. Families carrying small wooden stalls, miniature crafts, and baskets of typical dishes arrived at the fair’s entrance. Though parents and grandparents offered guidance, the children took center stage, each assuming the role of a vendor, artisan, or little chef. Their small kiosks dazzled with colorful miniatures: tiny houses, minuscule cars, miniature diplomas, and even mock passports—symbolic tokens that, by tradition, stand in for real-life aspirations.

The word “Ch’iti” originated from Aymara plus means “small” or “tiny,” which shows the festival’s attention to miniatures. The atmosphere buzzed with excited talk next to sales pitches: “Buy a small suitcase for good fortune in travel” and “Pick up two tiny lovebirds to make your love special this year.” Children as young as seven or eight perfected their sales pitches, standing behind their counters while wearing aprons, cholita skirts, or miniature police uniforms for a playful sense of realism. Each kiosk echoed adult vendors’ stands at the main Alasita event—except these were scaled down to a child’s imaginative perspective.

Many visitors stopped to witness how seriously the children approached their roles. A 10-year-old might discuss the meaning behind a miniature “house” purchase—that it symbolizes a wish for homeownership—just as attentively as seasoned adult sellers. Some kids showcased well-crafted mini art pieces; others served minuscule plates of traditional dishes, including the “anticucho” or a “chicharrón” dish in child-sized portions. The underlying message: these traditions, shaped by centuries of Andean belief, do not belong exclusively to older generations. If children take them up with sincerity, the spirit of Alasita will continue to flourish.

Adults lined up at the children’s stands to find the perfect New Year symbol. The cheerful grandparents took turns and gave gentle hints about making the correct change, following tips for displaying tiny figurines. Parents showed their happiness and remembered how their mom and dad explained this unique festival’s meaning. For all, the ephemeral scene—a labyrinth of mini kiosks that stood just a few feet off the ground—captured the essence of cultural continuity. The next generation was stepping forward to preserve and reinterpret ancient customs in a display that was as joyful as instructive.

Even the local government recognized the value of the Ch’iti Feria. The municipal officials walked through the area, greeted children, and took photos next to commended them for their business spirit. Some guests remarked that “these children are the future artisans of Bolivia,” which showed how much they value cultural heritage by investing in kids’ curiosity. A few young sellers shared remarkable stories: Some belonged to families who participated in the fair for four or five generations and displayed vintage family pictures and tales about their ancestors. Other children just started this tradition but felt passionate about it as they connected to something more significant in their community.

The bite-sized food specialties stood out at the fair. Kids wearing chef’s hats and little aprons served morsels of well-known Bolivian dishes, including emparedados de cerdo (pork sandwiches) and anticuchos, a skewer of beef heart and potatoes. While the portions were scaled down to childlike proportions, the flavors evoked the hearty satisfaction of Andean cuisine. For many participants, bridging artistry, food, and festivity illustrated the festival’s fundamental nature: a communal event uniting everyone through creativity, faith, and gastronomic flair.

Crafting Miniature Hopes and Dreams

Alasita, in the Aymara language, literally translates to “buy me.” Steeped in Andean tradition, the festival revolves around purchasing miniature versions of real-life desires—homes, cars, money, travel tickets, or professional documents—believing that once ritually blessed, these symbolic items will foster attaining those dreams in the following months. Historically, such miniatures originated in deeply spiritual contexts: small figures called “illas” representing fertility or prosperity were offered to ancestral deities around the summer solstice in the Southern Hemisphere. Over time, the custom adapted, taking on local nuances across various Bolivian regions but preserving the notion that a miniature stands for a fervent wish to be fulfilled.

The Ch’iti Feria revitalizes the deeper meaning behind these tokens by featuring children as leading vendors. When a 10-year-old sells a “mini diploma” plus shows it off with pride, it reminds people that this sale goes past simple trading. The act reflects how we believe in symbolic meaning. A buyer wants to finish an actual degree, get a promotion, or help their child do better in school. Handing over a few coins for a miniature script is akin to stating, “I claim this academic success for the coming year.”

Small “billets de Alasita” or “Alasita banknotes” were displayed in many stalls. Often, these notes replicate real currency denominations in decorative, whimsical styles. Some depict the infamous Ekeko, a jolly figure loaded with items on his back, known as the bringer of prosperity. Others replicate authentic Bolivian banknotes in a fraction of the size. As the kids sold these notes, they recounted how acquiring miniature money is believed to attract financial stability. Meanwhile, rummaging through the stands yielded glimpses of little suitcases, houses, trucks, and passports—further fueling the imaginative realm that merges aspiration with tradition.

Curiously, the festival also integrates elements of Andean spirituality in forms like “sahumar,” the smoke-based ritual of blessing items with incense or aromatic herbs. A 12-year-old might wave smoldering palo santo or other herbs, encouraging buyers to pass their newly purchased miniatures through the fragrant plumes. These actions evoke blessings from Pachamama, or Mother Earth, a revered figure in Andean cultures believed to nourish and protect her children. For the Ch’iti Feria, children become spiritual facilitators and enthusiastic entrepreneurs, bridging the gap between ancient rites and a modern sense of playful fun.

This balance—between the seriousness of an ancestral belief system and the lightheartedness of a children’s fair—makes the Ch’iti Feria a delight to attend. In a single day, visitors can watch a seven-year-old, decked out in a miniature business suit, waxing eloquent about the significance of a mini contract that might represent a future job opportunity. Nearby, a group of children in cholita attire might set up a small stage for a brief dance performance, swirling their polleras (pleated skirts) to show the same cultural expressions that their grandparents once did. Every object sold, every short show performed, weaves the old and the new together, creating a tapestry that reaffirms Bolivian identity.

Preserving Cultural Roots Across Generations

The children who participate in the Ch’iti Feria are typically direct descendants of artisan families who have taken part in Alasita festivities for generations. These lineages sometimes stretch back five or six generations—an unbroken chain that has witnessed Bolivia’s political upheavals, economic transformations, and cultural evolutions. Parents tell stories about how they learned their sculpting and weaving skills from older family members and mastered the art of creating tiny objects from clay, wood, or recycled items. The parents now pass these special abilities to their children, which lets their family’s artistic heritage thrive.

Many families preserve old albums featuring black-and-white photos of grandparents selling similar wares half a century ago. The families weave personal heritage and communal traditions together by displaying them at the children’s stands. One child might proudly point to a faded photograph: “That’s my great-grandmother, back when she wore a simpler pollera to the fair. We still use her original design for some of our tiny houses.” The viewers then witness how small cultural details endure or adapt over time. The polleras might now feature more vibrant modern dyes, or the hats may reflect contemporary city fashion, but the underlying artistry remains.

This transmission of knowledge goes beyond manual crafts. Children also internalize the symbolic and spiritual dimension, learning that these miniatures come to life mystically through rituals and blessings. They observe how elders measure out small amounts of incense, recite blessings in Spanish or Aymara, and sprinkle consecrated water or wine on the stands. The practice creates wonder in children and shows them how making things connects everyday life with more excellent spiritual ideas above us.

The event includes cooking traditions to help with the teaching process. While artisanal crafts might be the fair’s bedrock, the gastronomic offerings—anticuchos, chicharrón, or mini tamales—reflect heritage just as profoundly. Cooking at the fair has a generational lineage, too. In many families, grandparents serve as the keepers of recipes, ensuring that the marinade for the anticuchos has the right combination of spices. The kids gain kitchen experience early, adopting roles like measuring ingredients, frying miniature versions of typical dishes, and learning to present them attractively. Young cooks learn to value food in a new way throughout the festival period. They noticed that food means more than just nutrition; it also plays a vital part in Bolivian culture. The dishes connect to traditional music plus dancing next to local crafts. All these elements blend into a rich mix that represents Bolivian identity.

Local officials, along with cultural experts, believe such teachings matter. The main goal is to keep Bolivia’s cultural traditions alive plus active for future generations. When UNESCO recognized Alasita as part of the world’s artistic patrimony in 2017, it highlighted the tradition’s creativity, sense of community, and capacity to adapt over centuries. The Ch’iti Feria underscores adaptation: while the festival remains deeply traditional, it’s not an ossified relic. Instead, it pulses with the energy of a new generation, introducing digital influences (such as kids who might advertise their mini crafts on social media) alongside the ancient blessings once offered to illas and other deities.

Expanding the Legacy into the Future

Sustaining intangible heritage is both a challenge and an opportunity in the context of modern Bolivia, which is shaping its path toward technological growth and urbanization. The Ch’iti Feria stands at the forefront, proving that ancient traditions can remain vital if younger voices participate. Many children speak excitedly about combining new media with old beliefs. They might imagine a “mini laptop” or “mini smartphone” to be sold at next year’s fair, representing the hope for future success in a digital career or global connectivity.

Local leadership supports these modern twists so long as the essential spiritual essence remains intact. Indeed, the festival’s spirit rests on forging a connection between the ephemeral and the tangible, linking everyday desires—such as a stable job or a comfortable home—with the cosmic or religious significance anchored in Andean belief. Some kids might playfully print miniature airline tickets with popular world destinations, signifying that traveling remains a modern aspiration for many families. Meanwhile, older vendors recall how prior generations used to pray for donkey caravans to ensure transport across mountainous terrain. Technology shifts and evolves, but human desires for travel, growth, plus self-discovery persist through time.

A hopeful future lies ahead. The success of the Ch’iti Feria provides a model for other cultural festivals in the country. Towns near Cochabamba, Santa Cruz, and Tarija have started child-run craft fairs that follow the Alasita model. The kids organize tiny stands to display miniatures that show their local traditions. An elegant thing happens when they do this – it connects different communities and makes people proud of their origins. Children in the high plains might create miniature llamas or alpacas, while those in more tropical regions design tiny versions of exotic fruits or river canoes. A childlike view adds fresh energy to established traditions.

The festival serves as an excellent teaching tool for basic skills. When students run their booth, they learn to calculate numbers, serve customers, and master the art of marketing plus public speaking. They also develop creative abilities by adapting their designs to match buyers’ wants. Locals who prefer a more classic approach might purchase a mini crate of produce or a set of small clay figurines. Tourists or curious visitors from other parts of Bolivia or abroad might be interested in items that reflect a modern twist, such as mini laptops or pint-sized pop-culture references. The kids, in turn, glean real entrepreneurial experience. People express confidence when they share a token’s deep meaning plus combine business aspects with cultural stories.

The last hours of the Ch’iti Feria bring absolute joy as the sun sets behind the beautiful peaks next to La Paz. Parents help children pack up unsold items while the kids count their earnings or exchange leftover products among themselves. A small group starts a folk dance with quick steps as a young drummer creates steady rhythms. Night falls over the fairgrounds, but kids continue to laugh plus play. Each kiosk turns into a space of dreams and customs next to shuts down. The vendors know they kept Bolivia’s spirit alive at this festival.

Also Read: When Drug Cartels Threaten Music Stars in Mexico’s Tumultuous Frontier

The people who leave take miniature souvenirs along with a hopeful feeling. Those tiny figurines and mini plates of food mean more than just cute decorations – they show a legacy that connects old and young people. Inside every tiny suitcase or miniature diploma lies the story of a people who have endured and thrived, bridging the ancient Andean worldview with contemporary creativity. When a child wholeheartedly embraces that story—defending it with bright eyes and a determined smile—one cannot help but trust that Alasita, in all its magical miniature glory, will remain a cornerstone of Bolivian heritage for centuries to come.