Colombia Salt Cathedral Turns Zipaquirá’s Past Into Living Stone Underground

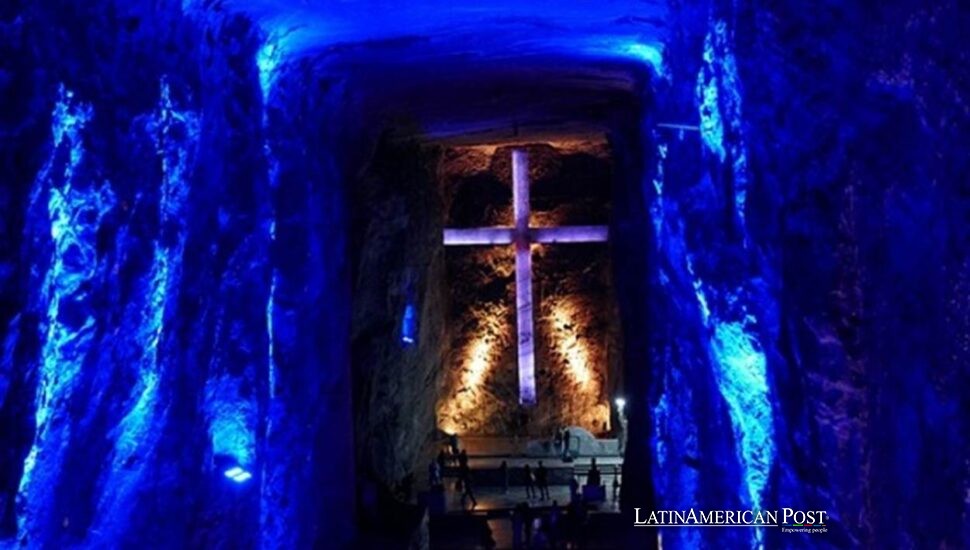

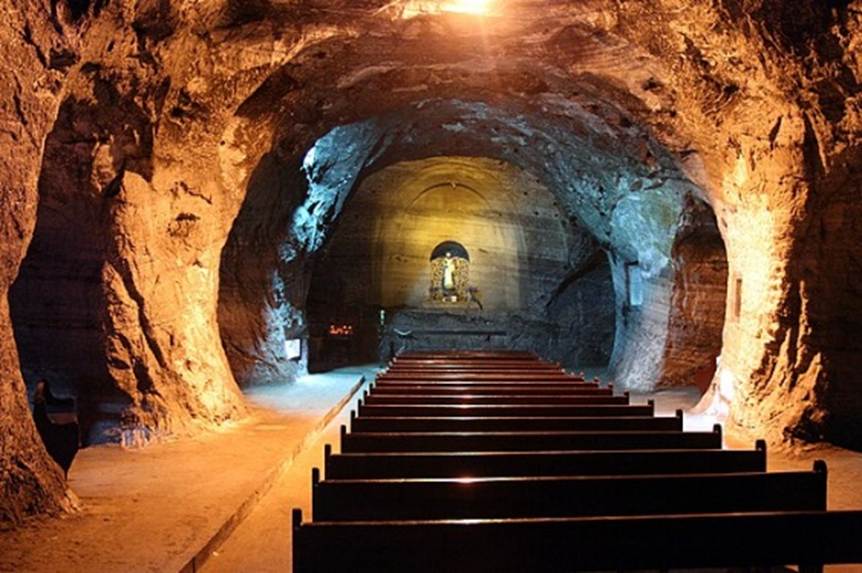

Inside Colombia’s Catedral de Sal de Zipaquirá, 180 meters underground, salt walls hold Indigenous memory and colonial ambition. Opened in 1995, it has welcomed over 13 million visitors, turning a mine into a national shrine,and a business of wonder still.

A Mountain That Learned To Speak In Salt

The descent is the point. You move through dark corridors washed in changing light, and the air itself feels older than the city above. A visitor, Monserrat Prito, described it with the kind of awe that doesn’t need polishing: “El pasar por esos pasillos oscuros… ver esas texturas y esos tallados… esas paredes de sal inmensas… en el corazón de una montaña una catedral de sal.” Her words land because they capture the place’s personality,half raw, half deliberate,where some chambers stay rustic, and others look patiently carved, as if the mountain negotiated with the chisels.

The Catedral de Sal is often filed under “tourist attraction,” yet the more accurate category is transformation. This is architecture that begins as labor. It lives inside a mine, and it refuses to let visitors forget that salt was once extracted here as a necessity, then as profit, then as power. Calling it a cathedral is not only about religion; it is about how a society chooses to honor what fed it and what exploited it. In 1995, when the current cathedral opened within the mine, it entered a new career: converting extraction into contemplation and the town of Zipaquirá into one of the country’s most recognized destinations.

That career has been wildly successful; more than 13 million visitors, from “different latitudes,” have made the trip underground. But the numbers do not explain the deeper magnetism. The cathedral doesn’t simply impress; it rearranges your sense of scale. The salt walls are not decorative; they are massive and intimate at once, like walking through a mineral memory. Heritage scholars in the International Journal of Heritage Studies have long argued that places survive by being reinterpreted rather than merely preserved. Zipaquirá has done exactly that, turning its most identifying substance, salt, into a narrative that can hold devotion, tourism, and national pride in the same breath.

Chicachica Before Bogotá And The Politics Of White Gold

Long before the cathedral became a modern icon, the land carried older names and older economies. Zipaquirá was once known as Chicachica, a Chibcha term meaning “pie del Zipa,” referring to the earliest settlement at the foot of the cerro del Zipa. Nearby, a zone called El Abra, framed by the Rocas de Sevilla, held evidence of human presence dating back roughly 13,000 years, including stone objects and material traces that later connect to Muisca ceramics. That deep timeline matters because it challenges the convenient idea that Colombia’s history begins with the Spanish arrival; the salt cathedral sits within a longer continuum of adaptation, trade, and survival.

In the altiplano cundiboyacense, salt was never only a seasoning. It was a supplement that made daily food bearable, a preservative that stretched scarce resources, and a commodity that stitched regions together. By the 16th century, salt appeared across towns like Nemocón, Tausa, Gachetá, Sesquilé, and others, but the densest sources clustered in places later folded into modern Zipaquirá, including Pueblo Viejo and El Carmen. What looks like geology on a map was, for communities, a strategic asset,one that inevitably attracted outside eyes.

Those eyes arrived with conquest. In 1537, Spanish troops pushed toward the territory after Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada encountered people transporting salt from Zipaquirá’s mines, reportedly near Barrancabermeja, and recognized the trade routes as a roadmap into the Muisca world. A commercial corridor took shape through the Magdalena River, not just as geography but as infrastructure for control. Scholars cited in the text, like archaeologist Marianne Cardale Schrimpff, underline that salt traveled enormous distances, reaching areas such as the serranía del Opón and the puerto de la Tora on the Magdalena, and moving southward in exchanges with Indigenous groups, including the Panches and Pijaos.

The production itself carried a social philosophy: collective, domestic, gendered. Anthropologist and historian Ana María Groot Sáenz emphasized that salt was produced by Indigenous women in their homes, with aguasal carried in múcuras, clay vessels, for at least three days. Several families monitored the cooking to keep temperatures steady, yielding about four arrobas across 18 múcuras. In a modern economy obsessed with scale, that detail reads like a rebuke. It shows a system built on careful attention, shared work, and community coordination,values that remain legible in the cathedral’s present-day choreography, where thousands move through confined spaces without fully noticing they are practicing, again, a form of collective discipline.

But the Spanish did notice, and they organized power around it. Encomiendas assigned labor and tribute; in Zipaquirá, the encomienda was granted to Juan de Ortega, and religious orders entered as administrators of belief, with Franciscans arriving in 1550 and Dominicans in 1553. The crown soon understood that whoever controlled salt controlled a revenue stream and a food system. Reforms shifted who held the monopoly, and new figures, like the Corregidor, a representative of royal authority with administrative and judicial reach, emerged to tighten governance over production and exchange. Salt became more than a mineral; it became a tool for building a colonial state.

From Encomiendas To Tourism And The Ethics Of Descent

The city above the mine was also engineered by that logic. In the late 16th and early 17th centuries, Spanish authorities restructured Indigenous life through resettlement and surveillance, creating the framework of the resguardo indígena and sending officials known as oidores to census and reorganize communities. Between 1593 and 1595, Miguel de Ibarra oversaw relocations in the Muisca territory; in 1600, Luis Henríquez visited Cipaquirá, criticized the deteriorated chapel being used as a granary and storage, spoke with caciques and captains, and on July 18, 1600, traced a new town under the name Zipaquirá. Even the dimensions of the church,8 meters wide, 42 long, 5 high,signal how the spiritual and the administrative were built together.

As centuries turned, so did technology, and salt’s “career” shifted again,from household production and tribute to industrial process. The text situates Alexander von Humboldt at the beginning of the 19th century, highlighting the dangers of open extraction and advocating the use of subsoil galleries. He recommended changes that sound technical but were really political: more efficiency, fewer collapses, more control. According to Alberto Corradine, “poco a poco fue desapareciendo la tradición indígena” as new tunnels opened and new systems replaced older practices. In 1803, Francisco Javier García introduced hornos de reverbero; by 1817, metal boilers were in use; by 1837, coal replaced wood. The mine’s voice changed from communal labor to industrial rhythm.

Then comes a figure who embodies Latin America’s recurring story of expertise arriving as both promise and disruption: Jacobo Wiesner, trained in physics, chemistry, mathematics, mineralogy, and mechanics, pushed new furnace designs and formalized underground galleries. In 1816, he opened the socavón de Rute; after the Batalla de Boyacá in 1819, Simón Bolívar named him Director General de Salinas. More tunnels followed: Guazá in 1834, El Manzano in 1855, Potosí in 1876,and the mine became a system, a road network beneath the earth mirroring the roads that spread across the surface to carry salt outward.

Modern Colombia is layered with still more change. Under President Rafael Reyes, administrative restructuring helped redraw regional governance, and in 1905, the Departamento de Quesada was established, tying Zipaquirá to broader state projects. By 1937, paving and pipeline infrastructure replaced the old brine transport system, swapping oxen for trucks and reshaping the city’s landscape. Salt shaped urbanism: streets, plazas, markets, royal roads, even a railway station. The cathedral’s modern success sits on that long accumulation of policy decisions, labor regimes, and infrastructural bets.

And yet, the cathedral today asks a question that statistics can’t answer: what does it mean to consume heritage without exhausting it? Journals like the Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development have explored how sites that blend spiritual meaning with mass tourism face a constant tension between reverence and revenue, between access and preservation. Down in Zipaquirá, that dilemma is not abstract. The cathedral is carved into a living deposit, and the environment is part of the message. The salt walls are not a backdrop; they are the archive.

That is why the most human reading of the Catedral de Sal de Zipaquirá is not as a spectacle, but as philosophy. It teaches that Colombia’s wealth has often been pulled from the ground,by Indigenous hands, by coerced systems, by modern industry,and that every extraction leaves a social imprint. Walking those lit corridors, you can feel the country’s contradictions: devotion beside commerce, beauty beside exploitation, national pride beside unresolved history. The cathedral does not resolve those tensions. It simply holds them, 180 meters underground, where the mountain seems to say what the region has always known: nothing valuable arrives without a cost, and nothing enduring survives without being reimagined.

Also Read: Argentina’s Ushuaia And Norway’s Longyearbyen Mirror Polar Extremes In Travel