Hidden Discovery Magnifies Picasso’s Genius for Global Art

By Trudy Pizano – LatamArt.com Curator

Under one of Picasso’s initial paintings from his Blue Period; researchers found a secret face through new scanning methods, which sparked discussions between museum experts and art lovers. The concealed image, which specialists at London’s Courtauld Institute of Art detected, shows how the artist changed his work. However, the discovery gives more insight into his methods of creation. This finding adds another piece to understanding Picasso’s approach during his early career. The emergence of this masked portrait beneath paint layers tells a story of artistic development through canvas reuse, a common practice for painters needing materials.

A Revelation Beneath the Layers

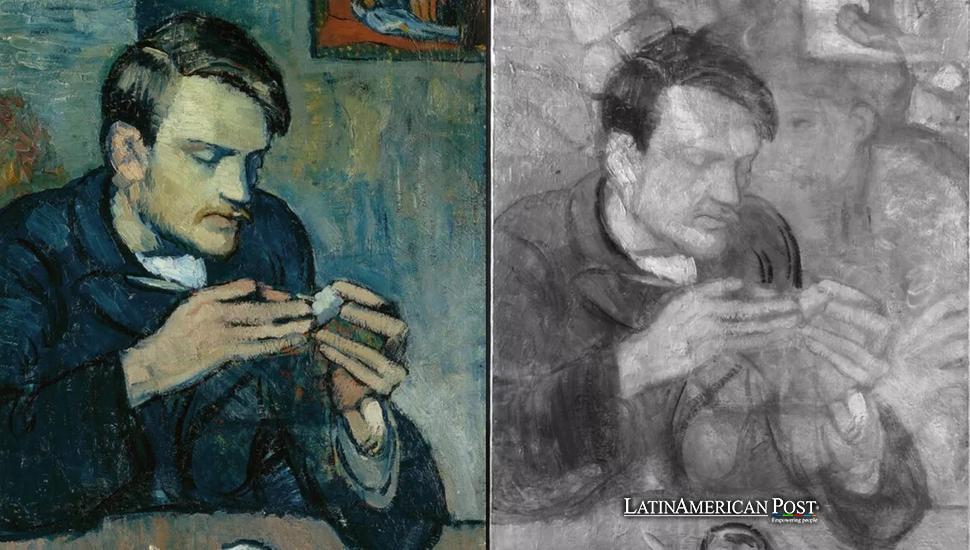

I read the recent developments regarding Pablo Picasso’s Retrato de Mateu Fernández de Soto (1901), fully aware of its importance during the painter’s so-called Blue Period. Yet the newly revealed figure of a mysterious woman—previously hidden for over a century—casts an entirely different light on how we might interpret both the painting and the tumultuous time from which it arose. Through my role as art curator, these paintings reveal the troubled thoughts within the artist’s mind. His works came from experiences in poverty plus emotional hardships. After his friend Carlos Casagemas died, the artist’s grief appeared in each mark of paint on the canvas. Through sophisticated X-ray and infrared imaging, we have encountered an additional piece in Picasso’s creative puzzle: a secret portrait beneath the visible composition.

The Courtauld Institute announced this discovery like a thunderbolt through the art world. According to their statement, the hidden image reveals the faint contours of a woman’s head, her hair piled in a bun, her shoulders in a stooped posture, and even the outlines of her slender fingers. The painting, therefore, has layers—not only in a literal sense, with brushstrokes and pigments stacked on top of each other, but also figuratively, in how we interpret Picasso’s early period. Upon viewing these newly released images, my initial inclination was to contemplate whether this portrait was a study for another piece or a wholly separate creation that Picasso opted to conceal for financial or aesthetic reasons.

Understanding an artist’s motivation for overpainting, especially when money is scarce. At the dawn of the 20th century, Picasso struggled with finances. It was common for him—and for many painters of that era—to reuse canvases, painting over previous efforts without bleaching them. Such a practice, newly revealed by advanced imaging techniques, should not come as a shock. What is surprising is how effectively technology has brought this hidden portrait into focus. Picasso, it turns out, left behind more than a single painting. He left behind multiple stories, layered one over the other.

The big question is whether further analysis can help identify this mysterious subject. Some might guess it was a model in Paris’s Montmartre circles or perhaps a personal acquaintance from Barcelona. The Courtauld specialists maintain their distance from definite statements at this stage since no signature exists on the piece. But questions without answers add intrigue to art research. The discovery brings renewed attention to shifts in Picasso’s techniques throughout his career.

Technological Breakthroughs and Creative Process

Each discovery through scanning equipment shows us what lies underneath masterpieces giving us facts about how artists worked. The scans provide actual proof of their methods, instead of relying on theories. During my time as a curator, I saw X-ray findings about Leonardo da Vinci and Rembrandt’s work. But Picasso’s paintings now undergo the same examination with X-rays and infrared reflectography. The results tell us clear information: no more need exists for speculation based on old documents. In place of assumptions, the paint itself reveals the truth.

One enthralling aspect of the newly unveiled portrait is how it reflects Picasso’s willingness to transform an image into something else. The Courtauld Institute’s deputy director Barnaby Wright described “marcas y texturas reveladoras” on the painting’s surface—features that hinted at an earlier composition. The art critic explained to EFE that Picasso changed his subjects from one form into another, which turned into a central element of his paintings and made him known across nations. Such remarks point to Picasso’s ever changing imagination through his early years, as he tried different methods to show what he saw in his mind. He was not just making do with limited canvases—he was refining a practice of reworking forms, an early step toward the radical reconfigurations that would characterize his Cubist experiments later in the decade.

As a curator, I have spent many hours explaining how and why artists repurpose materials to museumgoers. It is true that Picasso’s financial situation likely factored into painting over his earlier works—he was, after all, not yet the giant of the 20th-century art world. Yet, we should not reduce the practice to mere thrift. Picasso’s entire oeuvre is a dance of reinvention. Retrato de Mateu Fernández de Soto, a hallmark of his Blue Period, already conveys the bleak atmosphere that overshadowed his life at that time. Learning that it hides a second painting, presumably of a female sitter, reemphasizes how Picasso’s emotional and aesthetic transitions materialized on the same canvas. Over time, viewers will appreciate how that ephemeral female subject directly or indirectly influenced the final result we see today.

I imagine the technology at the Courtauld—X-ray beams, infrared scans, and data layers in real-time. The impetus is to map the slightest pigment variations. Suddenly, an entire silhouette emerges. Museums around the globe will, I suspect, re-examine their early Picasso pieces in the hope of discovering similar layers. The ramifications of curation are immense. Being able to share with the public the underlying images behind a masterpiece fosters an entirely new vantage point. No longer do we see the painting as a single, polished artifact. Instead, it becomes an evolving story of the artist’s restless experimentation.

The Blue Period’s Emotional Undercurrents

From 1901 until 1904, Picasso created paintings in a style that critics named the Blue Period, an interval that left marks on his future creations. His paintings shifted away from light shades toward cold blues and dark greens, which showed his turn to serious reflection. The colors he picked matched his mind during those difficult days. At its root stood pain from loss – his close friend Carlos Casagemas took his own life in 1901, leaving Picasso in despair. These somber shades replaced the lively colors of his previous pieces as he turned inward. The paintings from this time speak of sadness and reflection. In them, he put his grief onto canvas. This heartbreak and his experiences in Paris shaped the solemn mood of pieces like La bebedora de absenta (1901) or Mujer con los brazos cruzados (1901-02). The newly discovered composition beneath Retrato de Mateu Fernández de Soto may well date from that same existential crisis.

The woman’s identity is a riddle that has inspired many’s imaginations. Some people consider her a companion from Picasso’s circle of artists in Paris. Yet others believe she exists as one face among countless strangers he saw near his studio, a symbol of brief inspiration that came into his path. The identity stays hidden but her placement in the work shows how Picasso’s feelings influenced his art during those days. He might have begun painting her figure, only to set it aside when a more urgent or different vision seized him.

In that sense, the hidden figure parallels the emotional volatility of the Blue Period. It also questions the transition to more contemplative, even melancholic, imagery. Perhaps the woman’s half-finished outline no longer satisfied Picasso’s emotional or aesthetic goals. Feeling compelled to intensify the painting’s mood, he covered the first subject with the final composition: a portrait of Fernández de Soto, recognized as “one of the iconic paintings of Picasso’s bleak artistic stage.” The dynamic interplay of partial images, layered together, encapsulates the raw, searching energy that laid the groundwork for Picasso’s ascent as “one of the most important figures in the history of art,” as Wright puts it.

For me, the notion that this secret portrait physically underpins a recognized masterpiece encapsulates the emotional undercurrents of that era. So often, the Blue Period is singled out for its overt sorrow. But the Hidden Woman suggests that even within that sorrow, there was a range of potential narratives Picasso toyed with—and ultimately replaced. Thanks to modern science, he left them concealed for us to discover only now.

Implications for the Art World and Curatorial Vision

Through my profession as an art curator, such discoveries carry weight that defies measure. These findings exceed basic scholarly interest or minor details. The revelations transform our methods of exhibition design, alter our grasp of each creator’s artistic path, and reshape our understanding of society during specific periods. In the immediate sense, the rediscovered portrait is an added attraction—visitors are drawn to the drama of a “hidden painting.” Yet the deeper meaning lies in gleaning how Picasso’s process informs our broader understanding of the interplay between material constraints and creative impulses.

Given that the newly discovered figure “is similar in style to other works by the Málaga-born painter,” to quote the typical museum label, we see echoes of themes found in La bebedora de absenta or Mujer con los brazos cruzados. These connections might spur further inquiries about whether Picasso repeated or adapted certain poses across multiple pieces. Suppose this female figure evinces even a partial parallel with those iconic works. In that case, we might propose that the shape of her shoulders, or the tilt of her head, served as a conceptual stepping-stone for Picasso in forging his final composition of Fernández de Soto. This bridging of ideas from one painting to the next was typical of an artist who continually revisited and revised motifs.

On a practical level, the Courtauld Institute’s demonstration of X-ray and infrared technology stands as a clarion call for museums worldwide to investigate the hidden layers of not just Picasso’s art but the works of other early 20th-century masters. In museum archives, past purchases and overlooked paintings hide information capable of changing what scholars understand about art history. Behind each displayed canvas, previous sketches, and studies remain untold to visitors. The implications reach current painters, too, as their incomplete attempts and discarded drafts hold secrets that time will uncover in decades to come.

Finally, there are ethical considerations. Some might question whether it is acceptable to widely publicize hidden elements that an artist deliberately concealed—Picasso, after all, chose to paint over the figure. From my vantage point, the impetus for revelation outweighs potential moral dilemmas, provided we do so with respect for the painting’s integrity and historical context. In years past, Picasso’s death gave birth to deeper studies into his methods. Research into his work adds depth to our grasp of his talents. However, tests performed on the paintings need safeguards against damage to the materials. Researchers gather facts Through modern scanning methods without placing a finger on the paint surface.

The unveiling of an unseen Picasso portrait could easily overshadow the rest of Courtauld’s “De Goya al Impressionism” exhibition. Yet perhaps the synergy with Goya, Cézanne, and Van Gogh only heightens the broader message: that art rarely emerges fully formed but evolves through trial, error, and transformation. Goya’s unadorned style, the open spaces of Impressionist works, and Picasso’s dark shapes point to artists who broke from tradition. The x-ray analysis of Retrato de Mateu Fernández de Soto reveals a hidden form beneath its surface. Through the decades, artists have placed additional features across their canvases; in this case, the base strokes exist as a link between separate periods.

Also read: Latin America Celebrates Tattoo Art with Creative Expression

From my position organizing exhibitions, I value the opportunity to question previous ideas and update descriptions to spark new thoughts in visitors. The goal is for people to leave understanding that Picasso did more than paint – he created connections through decades with his art and feelings. X-ray scans reveal that every artwork stays active in its way. Past images exist beneath new paint, offering discoveries to those who come after us. But these respected works tell us more each time we look at them. Behind what we see lies another view proving that art holds endless secrets.

*Trudy Pizano is the curator for LatamArt.com combining her background in art history, art administration, and marketing to direct collections and shape exhibitions. As a curator with roots in Latin America, she discovers rising artists. Her studies bridge the gap between today’s society and Latin American traditions, which helps her select creators whose work reflects meaningful social themes.

LatamArt.com promotes appreciation for modern and contemporary art from Latin America. Through exhibitions and education, the platform gives space to artists from numerous countries across the region. The website brings together creators and viewers to examine cultural expressions of their times.