How a Colombian-American Artist on Death Row Helped Name a Killer

A nineteen-year-old mother vanishes in 1974. Decades later, a death-row painter in California befriends a serial killer and coaxes out the kinds of details that make cold cases breathe again. As Vanity Fair reported, listening—risky, relentless listening—changed everything.

The Nineteen-Year-Old Who Vanished—and the Silence That Followed

On the afternoon of January 3, 1974, Charlotte Cook left her Oakland home in knee-high boots, a blue sleeveless blouse, and a camel-hair coat. She was nineteen, a college student, and a young mother. The next day, a belt cinched around her neck, and she lay at the base of a bluff overlooking Thornton Beach. There were no arrests, no answers, and soon—no words. In the house where her absence hurt most, her name became a ghost. Her daughter, Freedom, grew up inside that hush. “I never knew what to think,” she later told Vanity Fair. For years, she did not even know her mother was dead.

The case settled into dust as Daly City’s oldest “active” homicide, open in name more than motion. The break, when it came, did not come from a detective with a miracle witness. It came from death row. William A. Noguera, convicted in 1983 and warehoused at San Quentin for thirty-six years, had fashioned a life out of lines—brushstrokes on canvas, tight loops in notebooks, the thin boundary between menace and rapport that lets one man speak freely to another whose company would curdle most souls. In that compressed world, he did what academics write about and rarely achieve: he embedded with a predator.

Noguera told Vanity Fair he carefully befriended Joseph Naso, the now nonagenarian former “Little League coach” and self-styled glamour photographer whose arrest in 2010 opened a gallery of horrors: a “rape journal,” pantyhose knots shaped into nooses, clippings about murdered women, and a handwritten “List of 10″—terse, place-coded descriptors that prosecutors would one day call a roadmap. Naso was convicted in 2013 of four murders. Investigators suspected many more. Evidence had cooled. Memory had hardened into myth. Into that void, Noguera stepped with a notebook and a plan.

He did it the slow way: coffee, candy bars, and a studied performance that said, in his words to Vanity Fair: don’t touch me, but do talk to me. He mapped Naso’s vanities, flattered his resentments, watched him preen at the word “art,” seethe when other killers were called “professionals,” and flinch at women who refused to bend. He was an exacting observer, and he was afraid—that much he admits. The mask was protection and bait.

A Killer’s Neighbor on Death Row Decides to Listen

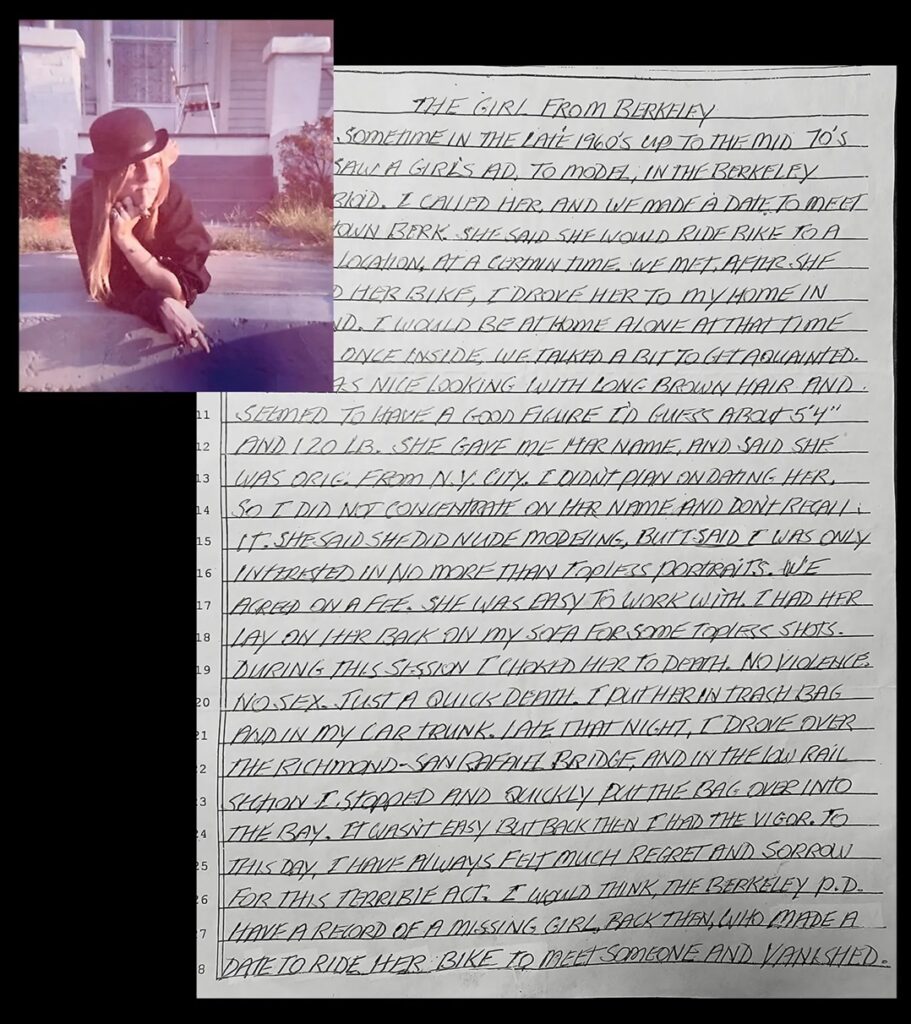

The intimacy of prison talk is its own anthropology. Brag becomes confession by degrees. According to Vanity Fair, Naso slid across a collage—women’s faces orbiting his portrait—and tapped his temple: they’re all alive right here. Over time, the boasts ossified into patterns, patterns into places, places into paper. In 2019 and 2020, Naso wrote Noguera letters that went beyond innuendo. One described the “Girl from Berkeley.” He said he’d answered a nude-modeling ad in the Berkeley Barb, met a young woman with shoulder-length hair, photographed her on his Oakland sofa, strangled her “quick[ly],” and tossed her into the water from the Richmond–San Rafael Bridge.

Those details were specific enough for Kenneth Mains, a former cop turned private investigator, to test against the missing. Mains, who had partnered with Noguera after receiving his prison notes, combed old files and found a near match: Lynn Ruth Connes, twenty, missing since 1976. Her bicycle was still chained at the spot where she’d arranged to meet a “photographer.” Her remains were never recovered. But as Mains told Vanity Fair, the family finally felt they knew who took her.

Another breadcrumb on the List of 10—”Girl from Miami Near Down Peninsula”—looked like nothing at first and then like a map. Miami Court is a tiny dead-end street in Oakland near an address tied to Naso. Peninsula News was a paper that covered Charlotte’s murder. In Vanity Fair’s reporting, Mains remembered one more stray detail Noguera had pried loose: Naso bragged about a victim’s “kick-ass jacket.” Charlotte’s police file notes an “expensive camel hair coat”—the same detail that helped her father identify her. The logic clicked. Daly City detectives, already warming the file, followed. “I believe Charlotte Cook to be the [victim] in the List of 10,” Detective William Reininger said to Vanity Fair.

Listening had turned rumor into leads. Leads began to turn grief into direction.

The Detective on the Outside and a List That Haunts

Suspecting a serial killer is one thing. Moving agencies to act is another. Coaxing the killer to keep talking is a third marathon entirely. Here, Vanity Fair traced a through-line: Mains—compact, tattoo-sleeved, running his Unsolved No More channel—took the prison-cop partnership pro bono and brought discipline to the flood. Together, he and Noguera built a file now threaded through conversations with the FBI and departments from Northern California to Las Vegas and Rochester, New York.

The List of 10 sets the frame. The objects from Naso’s Reno home widened it: mannequins posed like bodies, lingerie, pantyhose nooses, twenty-six gold coins, a ledger of assaults. According to Vanity Fair, Naso told Noguera the list was only his “greatest hits,” and boasted his actual number was twenty-six. He was unchanged from the man who flipped off jurors, called a female prosecutor a “whore,” and insisted his photos of nude, possibly dead women were “art.” A narcissist and a coward both; the same mouth that sneered at “whores” begged for protection after antagonizing an Aryan Brotherhood inmate on the yard.

To drag talk toward evidence, Noguera and Mains fixated on sticky facts—the humble engine of cold-case work. Naso said he “hunted” at Oakland A’s games with forged press credentials. An aspiring actress, abducted after meeting a “photographer” at Fisherman’s Wharf, turned up posed near Mount Tamalpais. Authorities once floated Rodney Alcala, the “Dating Game Killer,” in that case. Mains told Vanity Fair the posing, timeline, and geography fit Naso better, and he alerted the Marin County Sheriff. The office is now assessing whether Naso had “any potential involvement.”

In Las Vegas, Mains ran facial recognition against a collage Naso had given Noguera and flagged a possible link to a 1979 disappearance; police reopened the file, then later said no new leads emerged. In Rochester, a retired detective revisiting the notorious “double initial” child murders finally saw Naso’s rape journal, which described prowling a plaza where one victim was last seen. The current investigator told Vanity Fair that DNA excludes Naso in one case, but he remains a suspect in the other two.

And always there was Charlotte. As Vanity Fair recounted, when an FBI agent and a Daly City detective visited Naso at the prison hospital in Stockton, they dangled the one lure that still mattered to him: a move to a more comfortable facility, closer to his sons. He refused, then called them back as they reached the door. “You meant cold cases, right?” he said. “Okay, I think I could do that.” Freedom Cook, a lifetime of anger without an object, felt something shift. Thanks to Noguera’s work, she told Vanity Fair, she could finally let the rage land—and let some of it go.

@adminlpVanityFair

What Confession Means for the Living—and the Work Left Undone

True-crime stories often focus on the chase and overlook the people who must carry the consequences. Vanity Fair stays with them. There is Rachel Smith, four years old when her mother, Carmen Colon, was murdered; the trial was grotesque, but it opened—finally—a path to healing. There is Lynn Connes’s brother, a cemetery caretaker, standing by a headstone that still reads “Missing,” telling Vanity Fair he is “99.9 percent sure” now what happened to his sister. There is Freedom, looking at Charlotte’s photo and seeing not a cold case but a mother. “She was beautiful,” she said. “Always a sharp dresser.” She can hear the pitch that might have lured a young widow trying to raise two children: You want to take my picture? Where do I sign up?

And there is the messenger—imperfect, unignorable. At eighteen, Noguera killed his girlfriend’s mother in what he later recognized as a steroid-fueled rage. A jury sent him to death row. Decades later, he paints, writes, and claims he can tell when a killer lies by the way they remember what they wore. He does not offer study as absolution. He offers it as a utility. “Give back” is the phrase he uses in Vanity Fair—a phrase criminal justice veterans often hear with a flinch.

In 2024, a court resentenced him to twenty-five to life; with forty years already served, he became eligible for parole. The board approved, the governor reviewed, and on his sixty-first birthday, the grant was held. He stepped into California air in July, briefly snagged by an old warrant, then headed to In-N-Out. He is in transitional housing now, calling into Mains’s show, painting, writing, pressing agencies to reopen trails even as Naso tries to trade answers for a softer bed.

It is tidy to file this as a redemption parable: a killer helps catch a killer, a family hears a name, detectives find traction, and justice warms like a sunrise. Vanity Fair’s reporting declines that easy arc. Closure is rare. Bodies are missing. Trials may never come. The informant is a man who once made a mother vanish. The state preserved a serial killer’s life to keep him alive inside a system that no longer executes, hoping truth can be bartered from breath. And yet, stubbornly, the work goes on. A daughter can say her mother’s name without flinching.

A brother considers chipping away the word Missing. A veteran cop who once called the Naso evidence “Silence of the Lambs stuff” finds a phone number in an old drawer and dials.

Justice in cold cases arrives in fragments. Sometimes it’s a newspaper’s name that suddenly means a county. Sometimes it’s a dead-end street that becomes a compass point. Sometimes it’s the camel hair of a “kick-ass jacket.” And sometimes it’s a man on the inside who stops sketching roses long enough to sketch the outline of a monster—and listens until that outline speaks.

Also Read: How a Mexican Actor’s Road Rage Tragedy Ended in Prison and Heartbreak

The rest is endurance. The rest is a ledger that may never balance. But in rooms where silence once lived, there is, at last, the noise of names. And in the space where a nineteen-year-old mother disappeared, there is a line, however faint, that runs from a bluff above Thornton Beach to a prison tier in San Quentin, and back out again—toward a family that waited half a century for something like an answer.