Latin America is losing the fight against malnutrition

Food and nutrition security are not improving in Latin American – some 34 million people continue to suffer from malnutrition, 47.7 percent of children under age 5 suffer from anemia and 49.8 percent, approximately 1.3 million, have chronic malnutrition.

The figures “have not varied ostensibly in the region, they remain the same and are very worrying,” the World Food Program (WFP) regional director for Latin America, the Peruvian Miguel Barreto, told EFE in an interview.

Latin America and the Caribbean produce enough food to satisfy the needs of all their inhabitants, but the basic problem of food insecurity remains the same: the lack of access to nutrients, diets with little variety, high vulnerability to natural disasters and social inequality.

Barreto, aware of the vital importance of reversing this situation, calls for dealing with some “almost daily” problems with public policies and programs aimed at changing eating habits: “Not everyone who escapes extreme poverty is eating better.”

Which means there is no completely direct relation between the reduction of poverty and improving food security among a population, which also requires investing in “nutritional education” and promoting foodstuffs with levels of micronutrients that make up for what is missing in the local diets of the people most vulnerable.

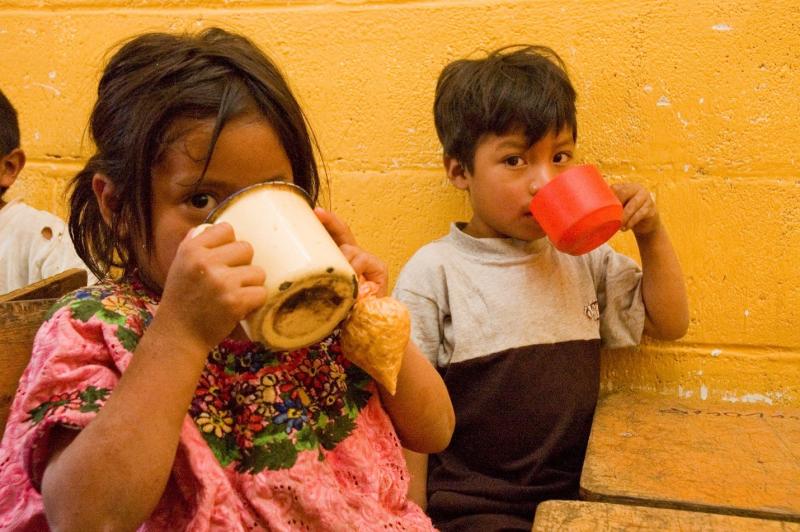

The daily diet in Guatemala, for example, is based on maize, beans, some vegetable and “now and then” an egg, which means access to products rich in phosphates and iron must be provided “without raising the cost of the basic food basket,” he said.

Identifying the micronutrients a population lacks, as an innovative WFP study did in Guatemala, will help the Central American country cease to be the country with the most chronic child malnutrition in the region: almost half the youngsters under age 5 suffer from that scourge.

“We must determine what the real problem is before we can solve it,” Barreto said, recalling that similar studies were made in Bolivia and Peru, which helped detect what was wrong and do something about it, because sometimes, he added, the problem is simply that the population doesn’t know how to use micronutrients.

Whether Guatemalan President Jimmy Morales can keep his promise to reduce chronic malnutrition in children under age 2 by 10 percent during his term (2016-2020), Barreto said “it’s pretty complicated,” since results take some 5-10 years to become visible.

The success of countries like Chile, Mexico and Uruguay in solving this problem was achieved by sticking to the plan and its strategies, goals and procedures: “Dealing with malnutrition requires a national accord that goes beyond just a presidential term in office.

Some 20 years ago, South African photographer Kevin Carter surprised the world with a picture of a starving Sudanese child being watched closely by a vulture. Critics called it sensationalism but for others it was just an everyday reality that continues to this day. In Latin America as well.