Mexico Remembers Through Film as Voices Refuse to Be Silenced

Half a century after the Tlatelolco massacre, a new Mexican film revives unfinished demands for truth, weaving together the 1968 killings, the disappearance of 43 students from Ayotzinapa, and today’s staggering toll of the missing. In No nos moverán, actress Luisa Huertas channels a nation’s memory, fury, and relentless hope forward.

The day bayonets entered the classroom

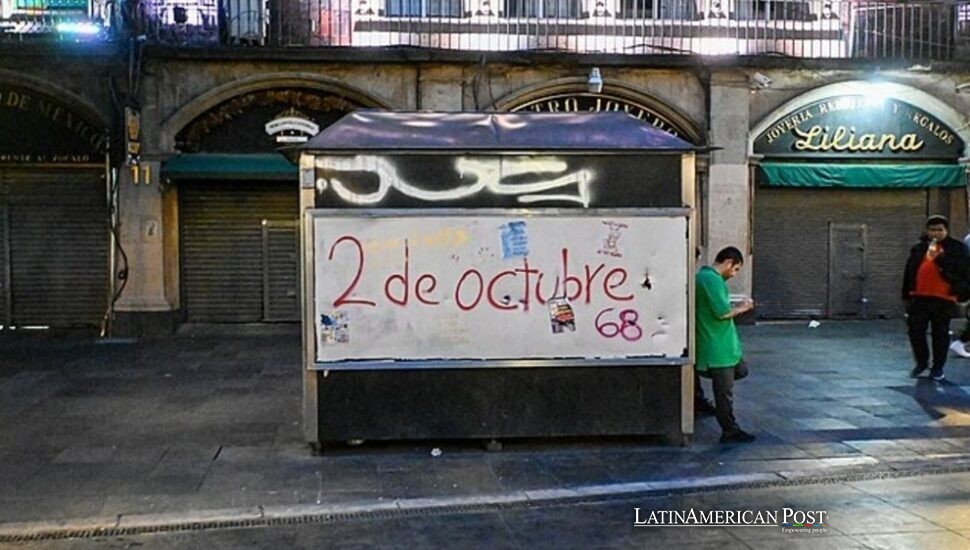

On October 2, 1968, Luisa Huertas was just 17, studying at Mexico City’s National School of Theatrical Arts. Suddenly, soldiers poured in—bayonets fixed, tanks idling outside, dogs straining at leashes. “How could anyone forget the moment the Army stormed the schools?” she told EFE, recalling the day she called “a watershed in Mexico’s history.”

Outside, Tlatelolco’s Plaza de las Tres Culturas had filled with a peaceful student protest. By nightfall, gunfire swept the square. Hundreds were dead. That trauma, still raw, forms the heartbeat of No nos moverán, a stark black-and-white drama that refuses spectacle and denies closure.

The film, directed by Pierre Saint-Martin, does not restage the massacre. Instead, it asks what five decades of unanswered questions do to those left behind. That choice gives Huertas, now 74, the most urgent role of her career: Socorro, an attorney who has spent 56 years searching for the man who killed her brother Jorge at Tlatelolco. “We didn’t want to restage the movement,” she told EFE. “We wanted to ask what happened to people who lost someone and still haven’t learned who was responsible.” Former president Gustavo Díaz Ordaz is “only the visible face,” she added, hinting at a deeper chain of command that remains obscured.

A sister’s hunt becomes the plot

Socorro’s search bends time. In her persistence, the audience sees today’s mothers digging through ravines with shovels and prayer cards; the parents of the 43 students who vanished in Iguala in 2014; the families still pinning photocopied faces to fences. Huertas leans into that continuum. “Their constancy and strength keep rubbing in our faces the inefficiency or the lies told,” she told EFE, stressing that the demand for justice has survived eleven presidential administrations.

The director drew from personal history—his mother’s activism and an uncle killed in 1968. Shot in luminous monochrome, the film works like a darkroom. Images long submerged surface again: the paramilitary Batallón Olimpia deployed alongside soldiers, whispered lists of the dead, corridors of bureaucratic shrugs.

Yet Saint-Martin resists despair. Small acts—a stubborn question, a painful laugh—keep the screen alive. The film has already made its mark: premiering at Cinélatino Toulouse, winning best Mexican feature at the Guadalajara International Film Festival, and earning a nomination for the 2025 Ariel Awards. The honors matter, but what grips Huertas is the silence after screenings, when teenagers linger to talk. “Young people aren’t as politicized,” she admitted to EFE, “but we’ve confirmed it moves those under 18.” That, she said, is the hope of any artist: to spark something that won’t let the audience leave unchanged.

From Tlatelolco to Ayotzinapa, memory refuses to sit down

The film’s title, No nos moverán—”We will not be moved”—is less a slogan than a demand. It stretches across eras not to conflate tragedies but to mark their shared root. Tlatelolco, Ayotzinapa, the more than 130,000 people officially listed as disappeared—all trace back to one word: injustice.

“You can’t keep ruling only through repression to silence dissent,” Huertas said, recalling the PRI’s iron grip of the 1960s. Yet the machinery of erasure—sealed files, blurred orders, diluted responsibility—has outlived that party’s dominance. Today’s Mexico counts new victims even as old cases stall.

The link to Ayotzinapa is explicit. Socorro’s dogged search mirrors parents who still sleep in tents outside government buildings, clutching forensic reports riddled with contradictions. “Their fight is our present,” Huertas told EFE. The film’s black-and-white palette underlines the moral clarity of their demand while acknowledging the gray fog of official narratives. Each office door slammed in Socorro’s face echoes the families in Iguala who ask again for what should have been delivered at once: truth. In a country where “never again” has often become “not yet,” the movie insists memory is not an archive but a civic muscle, flexed until it changes posture.

Holding on to the human voice

After five decades on stage and screen, Huertas talks about legacy without sentimentality. For her, it lives in a classroom. In 2006, she founded the Centro de Estudios para el Uso de la Voz (Ceuvoz), convinced that democracy depends on citizens who can inhabit and defend their own voices.

“We want to preserve—and more so now, in the age of artificial intelligence—the human voice as a real privilege,” she told EFE. “This is our sound; every species has its own. Our aspiration is that the word be ‘diciente’: that it says, expresses, protests, fights.”

That mission hums through No nos moverán. Socorro’s voice breaks but never disappears. In a nation where silence has often been policy, the film argues for speech as public service.

Also Read: Argentina to California Phalaropes Stitch Continents as Lakes Vanish

What does justice look like after so many years? The movie does not hand down a verdict. It does something braver: it keeps witnesses awake. It reminds Mexico that memory is not passive—it is an obligation. The teenager who once flinched at bayonets now embodies a woman who refuses to stop knocking. The audience watches, stirred and implicated. The title becomes a promise. We will not be moved—away from history, away from each other, away from the work of telling the truth until it changes the country.