Nicaragua’s Pioneer Stateswoman Who Beat Ortega and Sought Harmony

When Violeta Barrios de Chamorro stunned the hemisphere in 1990 by unseating the Sandinista revolution, many Nicaraguans saw only a grieving widow in a white dress. They soon discovered a steely publisher determined to cut rifles in half and teach a war-addicted country how to breathe.

From Editorial Ink to Blood on the Asphalt

In the 1960s, the La Prensa newsroom smelled of hot lead type and fresh coffee. Its owner, Pedro Joaquín Chamorro, pounded editorials that dared to write “dictator” under Anastasio Somoza’s portrait. Censors slashed columns, soldiers raided presses, and Pedro collected bruises in jail. Violeta, the rancher’s daughter who once called politics “a man’s sport,” waited in the corridor with clean shirts and newsprint smuggled under her skirt.

On January 10, 1978, bullets shattered the windshield of Pedro’s Oldsmobile. Managua was filled with tear gas and fists; La Prensa printed black-framed blank pages—fury articulated in silence. Historian Richard Grossman later wrote that Pedro’s murder “pulled every social thread tight enough to snap,” uniting bankers, priests, and Marxists against the Somoza clan. Violeta marched behind the coffin, the hem of her black dress soaked by the tropical downpour, chanting, “¡Se acabó la zanganada!”—the farce is over.

Olive-Drab Disillusion and the Newspaper Guerrilla

The Sandinistas rolled into Managua on July 19, 1979, promising milk and literacy. They invited the martyr’s widow onto a five-member junta. Within months, ration cards replaced paychecks, press freedom shrank, and teenage conscripts vanished into the mountains. Violeta resigned, calling the new rulers “Somoza in fatigues.”

She re-armed herself with verbs. Every time soldiers padlocked La Prensa, she found another warehouse and another stack of Canadian newsprint. Mothers of drafted boys found their lament on her front page; so did Miskito villagers herded off ancestral land. Sociologist William Robinson credits those stories with eroding the Sandinista claim to speak for Nicaragua’s poor. Ink, it turned out, could nick an AK-47.

The Election Night Upset Heard Round the Isthmus

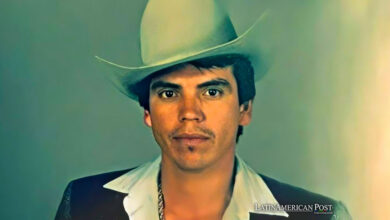

By 1990, the Contra war and a U.S. embargo had emptied shelves and hearts. Fourteen squabbling parties begged Violeta to lead a unity ticket. She appeared wearing white—the color of first communions—and said she had two promises: no more draft and a smaller army. Daniel Ortega scoffed that she was an “ornament.” Pollsters dismissed her; barrio mothers did not.

International observers led by Jimmy Carter watched ballot boxes fill. At midnight, the Interior Ministry’s tally showed Violeta ahead by double digits. She had no victory speech prepared, only a scrap of Psalm 30 in her purse: “You have turned my mourning into dancing.” The next morning, beside a cracked plaster lion on Managua’s old National Palace, she read the psalm aloud and dedicated the win “to Pedro and every widow of this war.”

Disarming the Volcano

She inherited a nation with 11,000 percent inflation and 81,000 men under arms—Latin America’s most significant military per capita. Conservative bankers urged mass soldier firings. Violeta chose a riskier path: She kept General Humberto Ortega—the enemy’s brother—as commander, betting continuity would prevent a coup. Over coffee, she told him, “General, I will be commander-in-chief; you will be surgeon. Our patient is Nicaragua.”

From El Almendro to Waslala, she stood on makeshift stages collecting rifles from contras who had spent a decade dodging MiG jets. One fighter handed her an AK-47 etched “Hasta la victoria.” Reporters caught when her small fingers closed over the weapon and lowered it, muzzle first, into a crate. Within two years, troop levels fell below 15,000; compulsory service died quietly, without a parade.

Inflation needed harsher medicine. With son-in-law Antonio Lacayo, she axed subsidies, floated the córdoba, and courted the World Bank. Prices stabilized, but jobs evaporated; supporters called her brave, and unions called her “Doña Austeridad.” She answered with another biblical line: “You cannot fill the granary if rats chew the floor.”

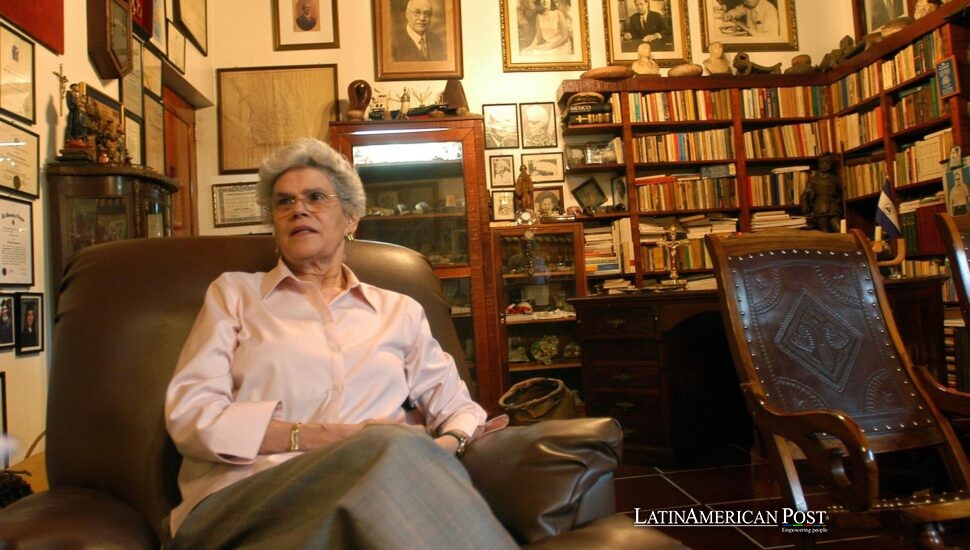

An Unfinished Conversation with Power

Violeta left office in 1997—press free, inflation tamed, but poverty unmoved. Daniel Ortega watched patiently, re-branding himself as a social democrat. 2006, he retook the palace, scrapping term limits and jailing rivals—including Violeta’s granddaughter Cristiana in 2021. Friends urged the aging matriarch to condemn him publicly. She demurred, citing a lesson learned around her mother’s cattle pens: “Sometimes shouting spooks the herd; better to open another gate.”

From her porch, she wrote cheques for the Violeta B. de Chamorro Foundation, training reporters in fact-checking—a mortal sin to new caudillos. Each Christmas, she sent books to rural libraries: Orwell in Spanish, Belli in verse, García Márquez dog-eared from her shelf.

Diagnosed with a brain tumor at 82, she moved to San José, Costa Rica, where the mountain air eased her dizziness. On June 14, she died as dawn lit the Central Valley. Her children announced the news “with gratitude for a life lived in service.”

Epitaph Written in Newsprint

She will be buried beside Pedro in Managua, a city where sirens still trigger old reflexes. Mourners will reread Psalm 30, and someone will place a folded newspaper on the coffin. The headline of her greatest scoop, printed the morning after the 1990 election, said: “GANAMOS“—We won.

Teachers from Ocotal to Bluefields use that front page to explain civil courage in classrooms. They say the widow in white proved rifles can rust, and tyrants can count wrong. They remind students—who know only Ortega’s second reign—that Nicaraguans once voted out a strongman and handed rifles to the mother of the war dead.

Years ago, Time asked Violeta how she had survived so many storms. Violeta touched a silver crucifix and whispered, “Fear is a luxury Nicaragua has never been able to afford.” On the day she died, La Prensa ran her words across the banner, black-edged. The presses groaned, the ink dried, and somewhere in the dictators’ archives, the paper cut like a fresh paper wound, still stinging after thirty-three years.

Also Read: Brazilian Master Salgado Remembered at Haunting Workers-Themed Display

Credits: Interviews with The Miami Herald, EFE, memoir Estación Carandiru; data from World Bank and Central American Historical Institute; polling by Vic Bulaich; U.N. demobilization records.