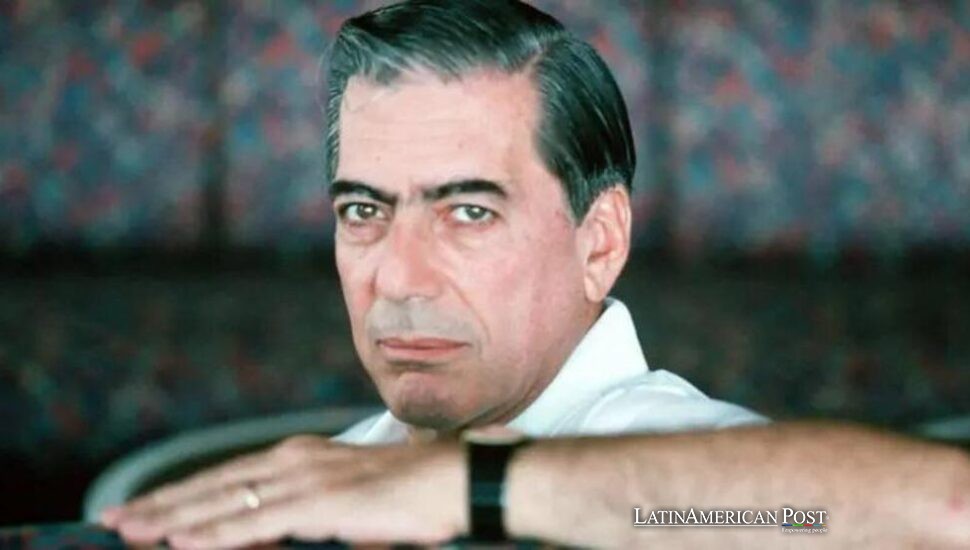

Peruvian Titan Bids Farewell: Mario Vargas Llosa’s Influence

For many years he dominated the literary scene and his political views sparked worldwide debate while his dedication to writing brought him acclaim from every corner of the world. The remarkable odyssey of Mario Vargas Llosa has concluded yet his unmatched contribution to world literature endures.

A Childhood Shaped by Secrets and Surprises

Mario Vargas Llosa entered the world on March 28, 1936, in Arequipa, a striking city in southern Peru often lauded for its white volcanic stone architecture. Despite always naming Arequipa as his birthplace, he spent only his first year there. His mother originated from a Peruvian family with strong traditions. The family structure broke when Ernesto, the father, left before Mario’s birth. This departure greatly shaped the child’s development. For a substantial time, Mario thought Ernesto was deceased.

At the age of one, Mario left Arequipa for Cochabamba, Bolivia, following his grandfather, Pedro J. Llosa, who had moved to manage a cotton plantation. Life there seemed almost blissful—one that Vargas Llosa would later describe as a kind of paradise, complete with a benevolent grandfather and a supportive network of female relatives. In that sheltered universe, little Mario spent days immersed in stories, newspapers, and any reading material he could find.

The peaceful rhythm of his early life ended dramatically around 1946 or 1947, when his mother revealed to him that his father was, in fact, alive. Not only was Ernesto Vargas alive, but he had suddenly returned to claim his wife and son. This shocking revelation, which Vargas Llosa recounts vividly in his memoir-like book El pez en el agua, proved a turning point in his life. His life altered completely in a short time. The father transported both the mother and the child to Lima, the capital of Peru. This began a difficult time characterized by a controlling father and inflexible demands.

In those first moments in Lima—a city Mario quickly deemed “detestable”—his father attempted to break the boy’s creative interests by sending him to the Leoncio Prado Military Academy at age fourteen. Instead of subduing him, this environment fanned the flames of his imagination. In his teenage years, Vargas Llosa felt the stirrings of a writer’s vocation: the violent collisions of social classes and ethnicities inside the academy became a microcosm of the broader Peruvian reality. All that would form the foundation of his earliest literary explorations and, eventually, his first major novel.

From “The City and the Dogs” to the Boom

At nineteen Mario took a significant action. He wed Julia Urquidi, his mother’s sister. Julia was eleven years older also had ended a previous marriage. This wedding surprised the family. It also showed Mario’s strong independent nature. That phase of rebellion, coupled with his new experiences working at newspapers and radio stations and as an assistant to various scholars in Lima, further honed his talents as both observer and raconteur.

His determination to become a writer never wavered, and all that discipline paid off in 1963 when he published The City and the Dogs (La ciudad y los perros). This work, composed in his mid-twenties, took direct inspiration from his teenage years at the Leoncio Prado Academy. Its gritty, unflinching portrayal of cruelty in a Peruvian military school both scandalized local authorities—who ceremoniously burned copies at the academy—and garnered him international acclaim. Almost overnight, critics and readers alike recognized Vargas Llosa as a major voice in Latin American literature.

Within a few short years, he confirmed his reputation as a daring stylist and social commentator with subsequent novels like The Green House (La casa verde) in 1966, Conversation in the Cathedral (Conversación en La Catedral) in 1969, and the mischievously comedic Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter (La tía Julia y el escribidor) in 1977. These books helped define the so-called “Boom” of Latin American literature, a movement that included Julio Cortázar, Carlos Fuentes, Gabriel García Márquez, and other titans of the written word. Their bold narrative experimentation and international success catapulted Latin America to the forefront of world letters in the 1960s and 1970s.

Although personal friendships bound many of the Boom’s authors, significant political discord emerged over the Cuban Revolution. Early on, Vargas Llosa was enthusiastic about Fidel Castro’s new regime; like many other young intellectuals of the time, he believed it represented a fresh, pluralistic form of socialism. However, events like the arrest and forced confession of the Cuban poet Heberto Padilla in 1971 shook this idealism. Along with other heavyweights such as Jean-Paul Sartre and Susan Sontag, Vargas Llosa signed letters condemning Cuban censorship. These events caused bitter splits in the once united sphere of Latin American letters.

Literary Power and Political Ambition

The late 1970s brought another change to Vargas Llosa’s worldview when he made London his home following his time in Barcelona and Paris. His European years brought him close to the ideas of liberal philosophers, including Karl Popper and Isaiah Berlin. He also observed Margaret Thatcher’s economic policies firsthand, embracing the idea of free markets and individual liberties as engines of prosperity—while still maintaining relatively progressive views on social issues like gender rights, marriage equality, and the legalization of drugs.

By the mid-1980s, Vargas Llosa was more than just a lauded author: he had become a public intellectual unafraid of taking political stances. In Peru, he was often polarizing. Opponents labeled him a right-wing neoliberal; supporters praised him for championing democracy and freedoms in a region repeatedly threatened by dictatorships of both left and right persuasions.

In 1987, this intellectual eventually stepped onto the political stage himself. He led the opposition against then-President Alan García’s proposed nationalization of banks, rallying significant public support. Buoyed by the momentum, he entered the 1990 presidential race as the candidate for the Frente Democrático coalition. Although his campaign started with strong momentum, he encountered a strong opponent, Alberto Fujimori, who presented himself as a people’s representative while labeling Vargas Llosa as elitist and disconnected. The defeat of Fujimori sent Vargas Llosa into such despair that he decided to leave politics for future endeavors. Returning to Europe, he wrote A Fish in the Water (El pez en el agua), a candid memoir that dissected his political ventures and family history. From that point forward, he remained an influential commentator on global affairs but never again sought office.

Despite the controversies, his literary achievements never waned. He continued writing at a relentless pace, producing novels, plays, literary criticism, and journalistic pieces. Already recognized with the Prince of Asturias Award and membership in the French Academy, he finally earned the world’s most prestigious literary honor, the Nobel Prize, in 2010. This recognition cemented his reputation as one of the leading novelists of the modern era—a writer of panoramic ambition who tackled dictators, historical cataclysms, comedic escapades, and erotic meditations with equal fervor.

Final Chapters and Enduring Legacy

Over his long career, Vargas Llosa penned around 20 novels, including landmarks like The Feast of the Goat (La fiesta del chivo), Conversation in the Cathedral, and The War of the End of the World (La guerra del fin del mundo). He authored theatrical works alongside gathering short fiction pieces and producing essays while providing journalistic columns that reached global audiences. His extensive travels took him to international conflict zones and political upheavals, yet he adhered to a strict daily routine. Friends and biographers often marveled at his unwavering regimen: Every morning, he began writing for hours after waking up at dawn, and he took detailed notes for his research while also revising his work continuously.

It was that same discipline that underpinned his late-career novel The Feast of the Goat, released in 2000. This penetrating examination of the Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo’s regime once again showcased the “total novel” style he had honed: multiple perspectives, historical authenticity, psychological depth, and a willingness to confront raw political terror. The work stands among his finest achievements and is lauded in the Anglo-speaking world as one of his greatest contributions to contemporary literature.

As he aged, Vargas Llosa’s personal life also made headlines. For decades, he was married to Patricia Llosa—his cousin—who had stood by him through financial struggles, multiple relocations, and his presidential campaign. Yet in 2015, he made front-page news by leaving Patricia for the socialite Isabel Preysler, then repeatedly appearing on the covers of celebrity magazines. Where he once disdained such media attention, calling it trivial, he found himself, in the twilight of his career, frequently ensnared in the paparazzi lens. The relationship ended in 2022, only to see him reconcile with Patricia soon afterward. Throughout these personal upheavals, he never truly retreated from intellectual life.

In 2022, at age 86, he became the first writer whose principal body of work was not in French to enter the French Academy—an unprecedented honor that placed him among the “immortals” of French letters. Not long after, he announced that his forthcoming novel, Te dedico mi silencio, would be his last, and he discontinued his enduring newspaper column “Piedra de Toque,” which he had published in various forms for decades.

His passing at 89 has left a chasm in the literary and cultural landscape of Latin America—and the world at large. As his children, Álvaro, Gonzalo, and Morgana, explained in their poignant statement, Vargas Llosa’s final days were spent surrounded by family. According to his wishes, there would be no public ceremonies, and his remains would be cremated in a private setting.

In many ways, Mario Vargas Llosa stood as the final representative of a once-dominant generation of Latin American literary giants. Writing amid civil wars, dictatorial regimes, and explosive social transformations, he and his peers—Cortázar, Fuentes, and García Márquez—set down a bold aesthetic that reshaped global literature in the latter half of the twentieth century. They brought to the page new linguistic textures, social critiques, and structural innovations, forging narratives that matched or even surpassed the grand complexity of the reality around them. Their work, known collectively as the “Boom,” continues to influence young writers from every continent.

Yet Vargas Llosa was also a figure of sharp contradictions. Even as he preached liberalism, he critiqued the unbridled excesses of capitalism. A champion of democracy, he fiercely opposed authoritarian regimes, whether of the left or right. He seemed comfortable defending a free market economy one moment and championing social reforms the next, bridging a spectrum of ideologies in a way that baffled more dogmatic thinkers.

Though he parted ways with the left-wing ideals of his youth, he always insisted that literature and culture must remain free from censorship and open to debate. In interviews, he emphasized that a healthy democracy requires diverse opinions, a vibrant press, and an engaged intellectual class—his voice echoing a creed of freedom that spanned continents and decades.

It is worth remembering that his shift to the political right in the 1970s and 1980s was never absolute. He continuously supported causes like the legalization of same-sex marriage and assisted suicide—positions often at odds with conservative mainstream platforms. In that sense, his brand of liberalism was nuanced and individualistic. The writer who once favored Fidel Castro’s revolution ended up praising Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, yet he never ceased calling for cultural pluralism, creative liberty, and an end to oppressive regimes worldwide.

Ultimately, the discipline that first caught fire in a military academy he “loathed” forged one of the greatest novelists and essayists of modern times. Vargas Llosa’s novels introduce readers to intricate patterns combined with exposed political conflicts and comedic elements that approach the ridiculous while maintaining a bold language that confronts ethical and ideological dilemmas.

His body of work demonstrates the influential strength of literature within Latin America which faces dictatorial governance along with revolutionary movements and societal turmoil. It is also a testament to a singular voice, one that refused to remain in any quiet corner of the world. Long after his departure, readers will return to his pages: to discuss them, dispute them, and draw new insights for years to come.

Perhaps Mario Vargas Llosa’s greatest legacy is this: he left behind a body of work that captured the Peruvian soul in all its complexity, documented universal struggles, and placed Latin America at the center of literary innovation. And in doing so—through passionate commitment and unwavering productivity—he achieved a universal stature that ensures his words will resonate far beyond his final days.

His children’s final note says it all: while sadness pervades their own hearts and those of his readers, they take comfort in the gift of a life rich with experiences and creative achievements. To read Vargas Llosa is to carry on his spirit, perpetuating that robust dialogue between reality and imagination that he guarded so zealously.

He may no longer be here to further provoke and inspire with a new novel, editorial, or witty speech, but his creations remain. The father-son conflicts he resolved, his travels across continents as he looked for literary success, and his changing political views all provided material for the stories he wrote. His life’s aspects enrich the tales he presents. Those narratives, built from the disciplined spark of a young boy who once despised the city of Lima and discovered his father was very much alive, will continue to spark conversations among readers across the globe.

Also Read: Abilio Diniz: Visionary Titan of Brazilian Retail and His Latin American Legacy

Mario Vargas Llosa’s departure marks the end of a towering chapter in Latin American letters. Yet like the great creators he admired—Sartre, Faulkner, Flaubert—he transcended narrow definitions, forging instead a robust, expansive tapestry of stories and ideas that future generations will decipher in fresh, evolving ways.