Unveiling Colonial History Key to Latin America’s Future

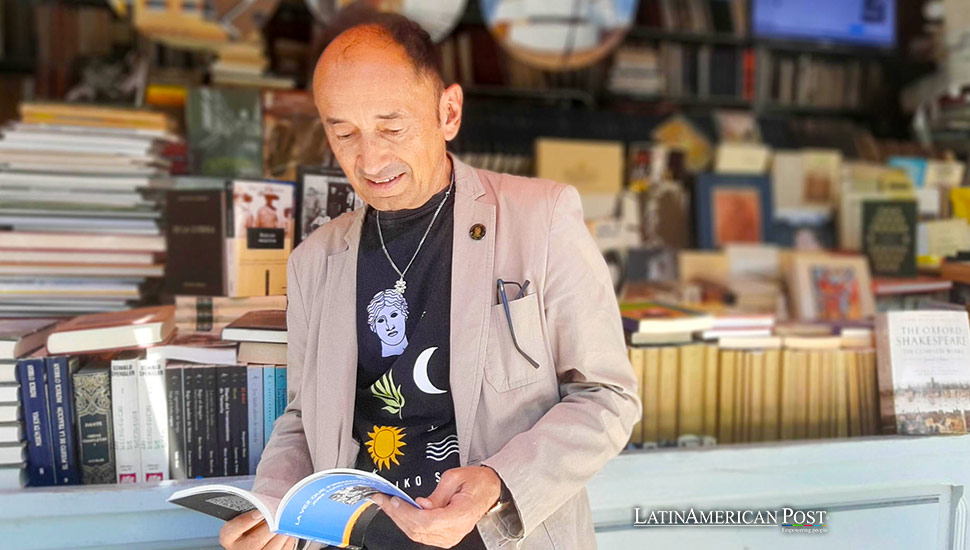

José Tono Martínez advocates for Spain to confront its colonial past and enact a historical memory law for the Americas, emphasizing the need for transparent and critical engagement with history to foster reconciliation and progress.

The Hispanic-Guatemalan writer José Tono Martínez, whose work holds significant relevance in the Latin American context, asserts that “there is no worse policy than hiding your past.” In his latest book, ‘La vez que firmamos la paz’ (‘The Time We Signed the Peace’), Martínez defends the necessity of bringing the history of the conquest of America and Spain’s colonial past into the open to recognize past errors.

In an interview with EFE, Martínez explains that his book contains four stories set in different American countries, all of which are “travel narratives with a common advocacy background.” He insists on the need for a historical “outing.” “Spain must take the step with a historical memory law for the Americas that allows us to acknowledge what was done wrong, recover the memory of the vanquished, and vindicate what was done right. There were also Spaniards who did things well, like Bartolomé de las Casas,” Martínez emphasizes.

Martínez, an anthropologist and writer, claims that “Spain was braver on this topic thirty years ago than it is now,” even though “now is the time when we talk about historical memory, revisionism, and cancel culture.” The first story in his book, ‘La vez que firmamos la paz,’ recounts how, in 1992, the president of the Spain’92 Foundation, Rafael Mazarrasa, representing the V Centenario Society in the United States, took a significant step in this direction.

“We were the representatives of the Kingdom of Spain regarding the Quinto Centenario events in North America. Initially, we were to organize parades and celebrations, but the program subtly changed. Ultimately, the central event was a meeting between peoples culminating in a ‘Declaration of Respect for Indigenous Nations and Cultures,’ signed on the 106th floor of the North Tower of the World Trade Center,” Martínez recalls.

When the Bicentennial of Latin American Independence was celebrated in 2009, Spain’s stance was “accompaniment,” a caution that Martínez prefers to describe as a “step back” and a “lack of courage to address the past with a sense of self-criticism.”

Spain’s Retreat in Addressing Colonialism

In the following years, Spain continued to retreat on this issue, preferring to look toward Europe and turn its back on Latin America, failing to recognize that Spain’s history is inextricably linked with that of America. However, Martínez, born in Guatemala, has not given up the fight. In ‘La vez que firmamos la Paz,’ he revisits that forgotten chapter of 1992 and other moments in recent and ancient history, encouraging a “brave analysis that allows us to rework our collective metaphors and choose which ancestors we want as our references.”

Martínez believes that addressing historical memory should also prevent the propagandistic revisionism of some Latin American leaders. He argues that Spain was courageous in tackling the historical memory of Francoism and should be equally bold with its colonial memory, following the example of countries like Belgium and the Netherlands, which have already begun to take steps in this direction.

Confronting Propagandistic Revisionism

“There are elements of indigenous tradition, such as their perspective on the environment, and chapters of colonial history, like the one led by Bartolomé de las Casas, with which new generations can identify and that could help them reconcile with their past,” Martínez asserts. He acknowledges a resurgence of imperialist stances that may use conquest narratives to push the issue back into the closet. Still, he insists that this is no reason to avoid the debate.

“On the contrary, Spain and Latin America need a cultural rearmament because if the debate is left vacant, that space is occupied by political outbursts, as is happening with the propagandistic revisionism of some Latin American leaders,” Martínez argues. He mentions Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega, and Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro as examples.

Citing Walter Benjamin, Martínez emphasizes in his book, “Yes, we can change history,” and further stresses, “We must do so because the harshest criticisms come from the next generations. If we leave a good legacy, we can, as Cornelius Tacitus said, ‘escape the future with dignity intact.'”

The debate over historical memory is not confined to Spain. In Latin America, countries grapple with their colonial past and the legacies of conquest. In Colombia, for instance, there is an ongoing struggle to reconcile with the history of Spanish colonization and its impact on indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities. The Colombian government has tried to acknowledge and address these historical injustices, but challenges remain.

In Mexico, President López Obrador has been vocal about the need for Spain to apologize for the abuses of the colonial period. This demand has sparked debate within Mexico and Spain about the importance of historical memory and reconciliation. López Obrador’s stance highlights a broader regional trend where leaders use historical narratives to shape contemporary political discourse.

Moving Forward: Embracing a Critical Historical Perspective

Martínez’s call for a historical memory law for the Americas aligns with a growing recognition that understanding and acknowledging the past is essential for building a better future. By confronting historical injustices and recognizing both the positive and negative aspects of colonial history, Spain and Latin American countries can foster a more inclusive and honest dialogue about their shared heritage, offering a hopeful path forward.

This approach is critical for educating future generations and preventing the repetition of past mistakes, a responsibility we all share. It also provides an opportunity to celebrate the contributions of indigenous and African-descended peoples, whose histories have often been marginalized or misrepresented.

Also read: Cuba Returns to Miss Universe After 57 Years

The debate over historical memory in Spain and Latin America is a complex but necessary endeavor. José Tono Martínez’s advocacy for a historical memory law for the Americas underscores the importance of confronting the past with courage and transparency. By doing so, Spain and Latin America can build a foundation for reconciliation and mutual understanding, ensuring that the legacy of colonialism is addressed with the dignity and respect it deserves.