Uruguay Embraces The Ocean Goddess And Renews Its Faith

Flowers, melons, popcorn, and homemade perfumes drifted across the gentle waves as hundreds of worshippers gathered on Uruguay’s beaches to honor Iemanjá, the “miracle-working” African deity. Each year, on February 2, Uruguayan followers of the Afro-Umbanda religion bring offerings to the water’s edge, trusting that the mother of the sea will bless their petitions.

Annual Rites For Iemanjá

When the sun sank, devotees came together at Montevideo’s Playa Ramírez. Most wore white clothes that marked spiritual purity. On the beach, they set up small altars with bright flowers, candles, or baskets full of fruit. A figure of Iemanjá stood among the offerings, dressed in pale blue and decorated with beads. The followers placed her near the gentle waves next to their whispered prayers for good fortune. “Salud y prosperidad para nuestra gente mamãe,” a worshipper said softly to the sacred goddess.

In Uruguay, a nation known for its secular governance, this Afro-Brazilian spiritual tradition thrives in pockets of devotion. Iemanjá’s feast day is the crowning moment for these worshippers, who celebrate the oceanic deity credited with granting miracles and forging hope in desperate circumstances. Families come from across the capital and beyond to wade into the Río de la Plata at twilight, releasing offerings on floating barges. Drums echo the call of ancient African rhythms, fueling dancing and chanting through the gloaming. For believers, the mere presence of Iemanjá invites the unstoppable force of water to cleanse and renew.

Yet these ceremonies also signal a defiance of the region’s religious majority, which for centuries scorned non-Catholic or Indigenous beliefs as backward or superstitious. Umbanda and other Afro religions often faced systematic marginalization—followers labeled as devil-worshippers, their orixas or saints maligned. Despite that, in modern Uruguay, the annual Iemanjá celebration has become not just a spiritual affair but also a tourist spectacle, attracting onlookers curious about the vibrant array of offerings and the haunting aura of nighttime worship by the shore.

A Day Of Miracles

Cloaked in tradition, February 2 has come to be known locally as a day of miracles, dedicated to “the mother of almost all orishas.” According to Umbanda lore, Iemanjá presides over oceanic waters and fertility. People with unfulfilled wishes—whether for recovery from illness, release from prison, or simply finding meaning in life—see a chance at the impossible in this celebration. “Many come to the beach yearly to thank Iemanjá for granting them the unexpected,” one Umbanda practitioner explained. She further noted the psychological comfort faith provides those who feel overlooked by society.

But the devout emphasize responsible worship. In years past, piles of artificial items—plastics, synthetic fabrics, elaborate figurines—drifted ashore after the ceremonies, causing ecological damage. Lately, community leaders have advocated more natural gifts like fruit, flowers, or shells. Offerings of watermelons, melons, or apples replace plastic items. Devotees aim to keep Iemanjá’s realm clean, showing a growing care for nature among followers who trust her guardianship of sea creatures.

Several believers must stay away from the packed beaches. Hospital patients, people in jail, and others who face movement limits cannot join in person. But followers say Iemanjá’s influence reaches everywhere. Those who stay apart still reach her spirit on that day as they ask for help or show thanks from distant places. The leaders suggest small home rituals or quiet corner prayers, proving her presence extends past the beach. The faithful thus believe every person receives Iemanjá’s gifts no matter their situation.

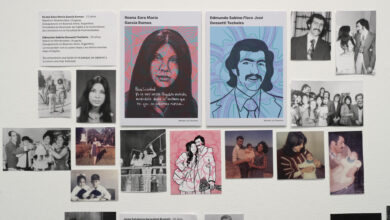

Battling Religious Prejudice

Despite the festive mood behind the drums lies a problem: “racismo religioso,” or religious bias, which Umbanda followers say still affects them. According to them, stigmas tied to African heritage portray Umbanda rites as macabre or heretical. Since Umbanda’s worship features orishas, drumming, and spiritual possession, some mainstream sectors label it “witchcraft.” This labeling drives many worshippers to practice in secret or avoid being seen entering certain temples.

Leaders point out that prejudice can flare into open hostility, vandalism of shrines, or harassment of practitioners. They mention a recent rise in incidents reported to Uruguay’s Human Rights Institution. As part of an initiative to combat stereotypes, Umbanda communities drafted a report to the United Nations detailing repeated abuses. They asked for international guidance on how to curb such incidents. In their eyes, gathering on beaches to celebrate Iemanjá is a public declaration of pride in Afro-Latin heritage.

In an op-ed titled “No todas son Flores,” one high priestess lamented the persistent offensive remarks, from calling adherents “negros cucumbers” to insinuating that Umbanda fosters dark magic. She underscores that these attitudes reinforce the historical othering of African-based faith. Activists hope to see official campaigns that address prejudices, much like how Uruguay gradually recognized other minority rights. Such reforms involve more robust public education, public service announcements, or the inclusion of Afro-Latin traditions in school curricula. By ensuring exposure to Umbanda beliefs, children might grow into adults who see no “darkness” in drumming and offering watermelons to an ancient goddess.

Spreading Iemanjá’s Presence

Although Iemanjá’s best-known statue stands near Playa Ramírez in Montevideo, worshippers dream of erecting monuments in other parts of the country. A dedicated group in Maldonado, the department that includes the famed resort Punta del Este, has spent years campaigning for an Iemanjá effigy by the city’s coast. Paperwork has moved at a snail’s pace despite local support. Organizers see a statue in the posh beach town as a triumph over old biases. They visited Playa Mansa with T-shirts championing the cause, seeking signatories, and sparking conversations about Afro-Latin religiosity.

The frontier department of Paysandú near the Argentine border needs a similar monument. Activists draw parallels between these expansions and Catholic saints in public squares: if Christian icons exist in city parks, Iemanjá deserves recognition at Uruguay’s riversides. The goddess’s presence means more than spiritual expression – it marks a shift that places Afro-Latin customs in Uruguay’s national story. Over time, if the goddess’s likeness stands in multiple provinces, they believe worshippers might feel less social shame in practicing Umbanda openly.

Furthermore, many hope these expansions attract an international tourism niche akin to pilgrims visiting shrines worldwide. If travelers witness Iemanjá festivals in multiple beach towns, the celebration could become a chain of events across Uruguay. Organizers mention potential spin-offs: music festivals, craft fairs selling Afro-inspired art, or guided tours explaining the spiritual significance of altars. Though still a dream, local tourism boards seem increasingly open to the concept, acknowledging the novelty and cultural depth that Afro-based ceremonies add to Uruguay’s usual tango and beach tourism.

The Promise And Challenge Of Iemanjá

Each February 2, crowds gather at the shoreline as evening approaches for a walk across peaceful waters. Traditional rumbas, along with candombe drums, create sounds that mix the heritage of enslaved Africans with Latin beats. The sight of boats filled with fruits drifting into the sea shows how small humans are next to nature. While cynics might dismiss the spectacle as mere superstition, participants say it bolsters communal bonds and offers spiritual healing in stressful times.

This tension between devout sincerity and outside misconceptions shapes Iemanjá’s presence in modern Uruguay. A new generation sees the festivities as a cultural jewel. They speak of forging music collabs, museum exhibits, or scholastic presentations about Afro-Uruguayan heritage. By promoting acceptance of Iemanjá, they address centuries of prejudice people of African descent face. “Her watery domain,” they note, “unites all worshippers, whether they are the wealthiest tourist or an impoverished single mother seeking solace.”

Still, the journey toward broader acceptance is bumpy. Religious leaders recount the daunting task of reversing decades of demonization. Mainstream acceptance remains partial at best. Though the public might smile at the once-a-year beach spectacle, more profound understanding or day-to-day respect is not guaranteed. Yet the persistence of dedicated Umbanda communities—organizing public ceremonies, pressing for monuments, coordinating social media campaigns—has resulted in incremental changes.

Ultimately, the day belongs to Iemanjá and those who revere her. The “mother of the waters,” believed to watch over births, fertility, and emotional well-being, remains influential in Uruguay’s population. Observers of the crowd find that many devotees kneel in the shallows, some with tears in their eyes, whispering personal confessions or pleas for health and security. The locals set basic baskets with gifts next to the water. People find comfort in the waves’ motion – a steady oath that returns to support their daily challenges.

Beyond the singing, dancing, and flame-lit altars, the more profound significance of February 2 lingers. In a society that historically neglected Afro traditions, individuals from all walks—some identifying as Umbanda faithful, others drawn by curiosity—coalesce in a shared act of devotion. The day’s ephemeral nature, culminating in a fleeting sunset ritual, underscores the ephemeral grace of the goddess’s blessings. Like the waves, events flow away into memory, replaced by the hope that next year’s festival might be more significant and freer from prejudice.

Also Read: Tsimane of Bolivia Share Secrets of Health in Amazon

Looking forward, the possibility that Iemanjá effigies soon stand in more coastal zones is heartening. If the mother of the waters can claim new ground along Uruguay’s diverse beaches, perhaps her unstoppable tide will wash away ignorance and stereotypes. She remains a symbol of redemption, acceptance, and the vibrant fusion of African diaspora traditions with Uruguayan identity. And for the thousands who braved the water each February 2, the moment is one of collective renewal—an abiding testament that while prejudice lingers, so do miracles.