Brazil Reveals Hidden Saga of Megafauna Living Longer

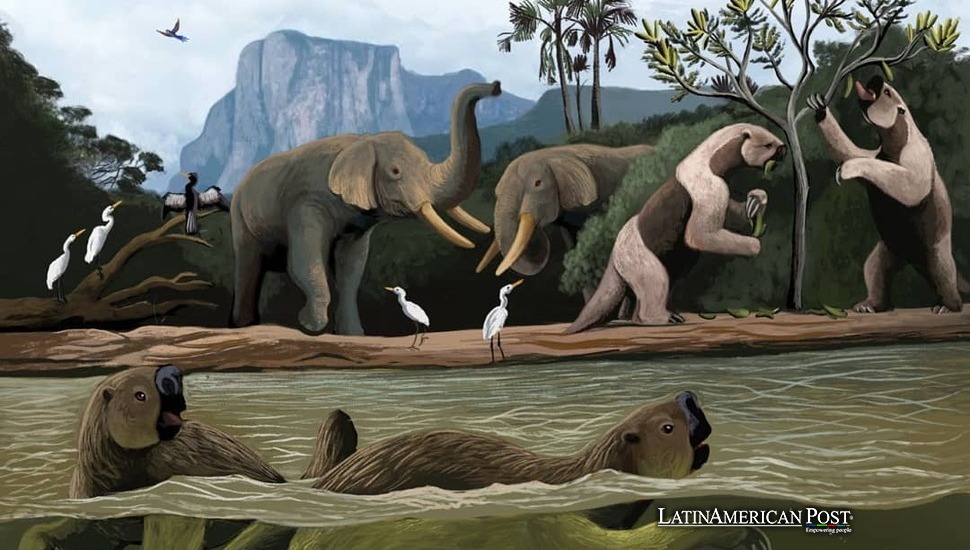

New findings in Brazil are overturning long-held assumptions about extinct giant mammals. Researchers have discovered that certain megafauna species survived far beyond their presumed extinction date, coexisting with early humans and challenging popular theories about their ultimate demise.

Rewriting the Timeline

For decades, the dominant narrative placed the extinction of most mammalian megafauna at the boundary between the Pleistocene and Holocene epochs, roughly 11,700 years ago. Creatures such as giant sloths, sabertoothed tigers, mammoths, and enormous camel-like herbivores were thought to have vanished by the start of our current geological period. Because of their size, these large species, called megafauna, once lived across many parts of the Earth.

However, new fossil remains from Brazil dispute this timeline. They show some groups of large mammals lasted thousands of years more than believed. This revelation is not entirely without precedent; paleontologists have already discovered evidence of woolly mammoths surviving up to about 4,000 years ago. Based on fresh discoveries in Brazil, it appears that at least some giant sloths and other unusual mammals, such as an extinct genus of American llama and a camel-like creature with a tapir-like nose, continued to exist as recently as 3,500 years ago.

It may sound like a relatively small extension of the known timeline, but another seven or eight millennia of survival is monumental in scientific terms. This means that, for millennia, these massive creatures inhabited the same landscape as early human communities in South America, who arrived somewhere between 20,000 and 17,000 years ago. The extended coexistence raises important questions about how humans and megafauna interacted and why these animals disappeared.

While global climate fluctuations at the end of the last ice age undoubtedly affected countless species, the puzzle now is determining whether that climatic upheaval alone caused the demise of these colossal creatures or if multiple factors were at play, including human influence. Suppose some groups survived in refuges where conditions were more favorable. In that case, that points toward a more prolonged extinction process than initially assumed instead of a sudden die-off triggered by a single event.

Discoveries in Brazil

Recent findings come from a team of researchers led by geologist Fábio Henrique Cortes Faria at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. They examined fossils extracted from two sites: one near Itapipoca and another in the Rio Miranda Valley. Through radiocarbon dating, they analyzed fragments of teeth belonging to several megafauna species, including Palaeolama central—an extinct genus of American llama—and Xenorhinotherium bahiense, a camelid-like creature sporting a nasal structure reminiscent of tapirs.

The shock came when a pair of these tooth fragments produced surprisingly young dates, roughly 3,500 years old. Under conventional wisdom, these animals should have disappeared far earlier, likely around 11,700 years ago, when the global climate transitioned into the present-day Holocene. The fact that these animals lingered well into the mid-to-late Holocene suggests an entirely different extinction dynamic than previously envisaged.

These findings run parallel to other parts of the world, where evidence has accumulated that the so-called “great megafaunal extinction” played out unevenly in time and space. Regions that once seemed uniformly devoid of large mammals after a certain point contain relic populations that lasted much longer. Whether such areas should be labeled “refugia” has become a topic of intrigue among paleontologists. If these environments had provided more food, shelter, and weather, they may have helped some species survive longer than expected.

Researchers also study how these large mammals could have come into contact with early people in South America. If humans and megafauna overlapped for thousands of years, it becomes less likely that humans alone eradicated these creatures through overhunting—an argument put forth by what is known as the Overkill or Blitzkrieg hypotheses. Under those theories, human hunters swept through continents, decimating large game in a relatively short timeframe. Prolonged coexistence without immediate extinction, however, undermines that scenario.

Reassessing Extinction Hypotheses

For years, scientists have been locked in debate over the primary drivers behind megafaunal extinction. A central contention has revolved around whether climate change or human activity played a more significant role. Climate shifts at the end of the last ice age were drastic: receding glaciers, warmer temperatures, and altered rainfall patterns transformed environments at a dizzying pace. Meanwhile, the argument for human-caused extinction, especially in the Americas, rests on archaeological and ecological evidence suggesting that newly arrived human populations aggressively hunted large game.

Yet the discovery that certain megafauna persisted up to 3,500 years ago—thousands of years after humans arrived—complicates any straightforward claims of a “rapid kill” scenario. If humans were alone responsible, extinction might have occurred soon after reaching South America. However, these new data show a long process and allow other explanations.

Brazil’s varied ecosystems may have served as safe places with steady climates, plenty of plants, and lower human pressure. Differences in altitude, proximity to water sources, or availability of mineral deposits made specific locales particularly hospitable to large herbivores. Over the centuries, as human populations grew and spread further, the pressures on megafauna likely increased. But that transition happened gradually rather than all at once. In that case, it further diminishes the likelihood that a single, uniform cause spelled doom for every species of large mammal in the region.

Such findings echo a broader reality in paleontology: extinctions are rarely neat or instantaneous on a continental scale. More commonly, some species live in scattered refuges, surviving for centuries or millennia past their initial expected death. This slow process fits the idea that local conditions, competition, disease, predation, and larger environmental factors create a complex pattern of survival and decay.

A Larger Picture of Survival and Loss

The idea that giant mammals persisted alongside human communities in Brazil 3,500 years ago effectively reshapes the timeline of Earth’s most recent large animal extinctions. Rather than concluding abruptly at the dawn of the Holocene, the die-off now appears to have been staggered over millennia. These findings matter more than academic interest; they show how climate change and human settlements existed with large animals in many regions.

One clear result is that old theories, especially Overkill and Blitzkrieg, now face reexamination. If, as the research team concludes, the evidence shows a lasting coexistence with humans, it suggests that direct human hunting might not be the solitary or even dominant factor behind megafauna decline in South America. A mix of factors—small changes in plants, water, diseases, slight hunting pressure, and broken habitats—might have met, leading to these creatures slowly vanishing over a longer time.

Furthermore, realizing that some species thrived longer in particular pockets of Brazil than elsewhere might inspire scientists to study the specific environmental or ecological conditions that preserved these populations. Such investigations could illuminate how specific habitats buffered climate extremes or offered reliable food sources for enormous herbivores. These ideas can guide today’s conservation work since the planet’s biodiversity crisis mixes climate change with human encroachment, similar to long-past long-past accounts.

Even though the study uses only a few fossil samples, it matters because it questions current views. Much like how the previous discovery of late-surviving woolly mammoths on Wrangel Island upended assumptions about global extinctions, the new Brazilian data further supports the conclusion that the collapse of megafauna populations was neither sudden nor uniform. By focusing on one region and generating tangible radiocarbon data, researchers have erected a new cornerstone in the ongoing debate about how, why, and when these massive species finally vanished.

In the future, more expansive fossil hunts and advanced dating techniques may unearth additional remnants of Pleistocene giants in unexpected places. The “late survival” notion could broaden to include even more species or other geographical pockets. Each new find nudges us to refine our understanding of prehistory. This iterative process continuously reshapes our perspective on the deep past and underscores the intricate relationships between climate, humans, and wildlife.

Also Read: Revealing Amazon Secrets With Lidar To Transform Archaeology

Brazil’s story shows that extinction rarely follows one pattern, even for animals that seem doomed by size or high resource needs. If they survived into the mid-Holocene at some sites, it proves that ecosystems vary and extinction causes are complex. Rather than a monolithic or short-lived die-off, we’re coming to appreciate a far richer tapestry of survival and loss—one that, millennia later, still holds lessons for humanity about stewardship, resilience, and the fragility of life in a rapidly changing world.