Mexico’s Forgotten Telescope Is Now Watching the Skies to Protect Earth

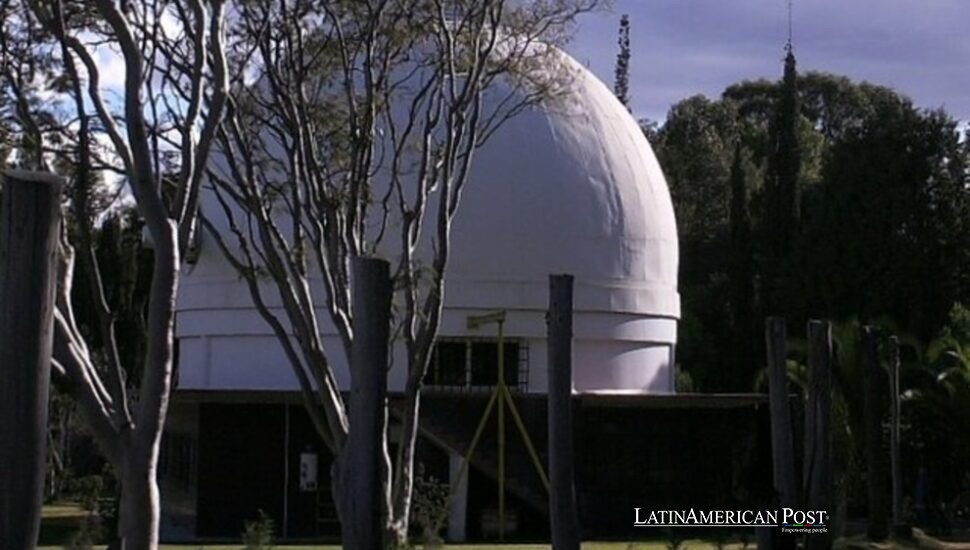

Each night from a windswept dome in Puebla, astronomers peer through an 83-year-old telescope hunting asteroids that could one day threaten Earth—quietly turning a historic Mexican observatory into a frontline post for planetary defense.

A War-Era Lens Now Tracking Future Impact Threats

The Schmidt Camera inside Tonantzintla’s observatory looks like something out of a Cold War museum: steel frame, thick lenses, a split dome that creaks open under the stars. But in the hands of José Ramón Valdés and his team of “Asteroid Hunters,” it’s become one of the most essential tools Mexico has for spotting trouble in the sky.

Valdés, a Cuban-born astronomer who now leads asteroid tracking efforts at Mexico’s National Institute of Astrophysics, Optics and Electronics (INAOE), climbs the spiral staircase each night the skies are clear, switches on the digital systems retrofitted into the old Schmidt, and begins scanning the heavens for near-Earth objects—space rocks that might, one day, be pointed directly at us.

“If we want to know which asteroids are dangerous, we must know them first,” he told WIRED, standing beside the decades-old control console that now feeds data to global space agencies. His team captures multiple exposures of the same star field across a single night. Automated software checks for moving dots—asteroids. If one shifts against the background stars and doesn’t match the global database, the team flags it and calls in backup. Within hours, observatories in other time zones begin tracking the object.

It’s meticulous work. But one confirmed trajectory could save lives.

Tonantzintla’s Past Shines Into the Future

Built during World War II, Tonantzintla’s telescope once helped Mexican scientists map the stars with glass photographic plates. In the 1950s, those plates captured what turned out to be blue supergiants and even some of the first quasars ever photographed, discoveries that defied contemporary astronomy.

That legacy still pulses through the dome’s brick walls. Guillermo Haro, Paris Pişmiş, and the González sisters trained there. Haro famously devised a way to extend the life of photographic stock by layering multiple exposures—a trick that allowed Tonantzintla to compete with far richer U.S. and European labs.

“Good engineering endures,” Valdés said, tapping the telescope’s side. It may creak, but it delivers.

Digitized versions of those glass plates are now being reanalyzed by artificial intelligence, seeking patterns the human eye missed 70 years ago. Some of those old negatives still show slow-moving objects—asteroids whose paths we’re only now understanding. That makes Tonantzintla not just a relic, but a living archive, one that bridges past discovery with modern defense.

And the observatory doesn’t stand alone. It anchors Mexico’s growing astronomy program, which includes the Gran Telescopio Milimétrico, one of the world’s most powerful millimeter-wave observatories, and HAWC, a gamma-ray detector that helped image the Milky Way’s central black hole.

From the macro to the minuscule, Mexican astronomy now spans the spectrum.

A Cuban Astronomer, a Mexican Mission

Valdés’s path to Tonantzintla wasn’t direct. He was born in Cuba, trained in Russia, returned to Havana, and only ended up in Mexico after meeting INAOE director Alfonso Serrano at an international astronomy school in 1989.

Serrano’s pitch was simple: come to Mexico and help build something new. Valdés never left.

“I’ve seen this place grow from seven astronomers to more than forty,” he told WIRED, crediting Serrano’s vision to combine astronomy, optics, and electronics—so Mexico could build its instruments, not buy them.

Today, the observatory hums with young researchers. Retired engineers like César Arteaga, who helped build the Guillermo Haro telescope, still show up to guide students through the quirks of aging hardware. Interns catalog old negatives by hand while training AI to read them faster.

“You can’t walk these halls without bumping into history,” Arteaga said, motioning toward a stack of crates filled with plates that once rewrote theories of stellar evolution.

The fusion of past and present is Tonantzintla’s hallmark. It’s a place where Cold War optics meet cloud computing. Where astronomers still log data by hand—and upload it to servers that speak with NASA.

Wikimedia Commomns

A Telescope That Can’t Stop Asteroids, But Might Save Lives

Back in the control hut, the monitors flicker with new data—blips from tonight’s sweep. Some objects are familiar. Others will soon get provisional names like 2025 AQ3. The team checks velocities and orbital curves. Most will never come close to Earth. But some stay on risk lists for years.

Valdés imagines a future where a young astronomer opens a file his team started and says, “This asteroid’s orbit was first measured at Tonantzintla a thousand nights ago.”

That kind of continuity matters. Mexico’s civil protection agencies now consult Valdés’s team. After a 2013 meteor exploded over Chihuahua, the government began drafting emergency protocols for potential airburst events. The public barely noticed, but astronomers didn’t forget.

“Planetary defense is like insurance,” Valdés said. “You hope the premium feels wasted.”

The work might seem invisible—but if one day it prevents a city-leveling strike, it will be among the most critical contributions Mexican science has ever made.

NASA’s recent DART mission proved we can nudge asteroids off-course. But first, we have to know they’re coming.

That’s Tonantzintla’s job.

In an era of commercial spaceflight and billion-dollar observatories, the old dome in Puebla stands as a quiet guardian—still scanning the sky, still logging threats, still making Mexico a key player in the planet’s defense.

Also Read: Rediscovered Jungle Fortress in Chiapas Revives Maya Resistance to Spanish Conquest

From Maya stargazers to mid-century visionaries, the tradition endures: not just to watch the heavens, but to understand what they might throw our way. And if one night, an old telescope helps save the Earth, it won’t be by accident. It’ll be because someone like Valdés was there, keeping watch.