Paraguay Sings Again as Lost Guaraní Verses Find a Digital Home

A forgotten literary magazine has been revived in Paraguay, bringing thousands of poems and songs in Guaraní, Spanish, and Jopara into the digital age. Rescued from an ambassador’s suitcase and restored by local partners, it now flows again after decades of silence.

A river of words, dammed and released

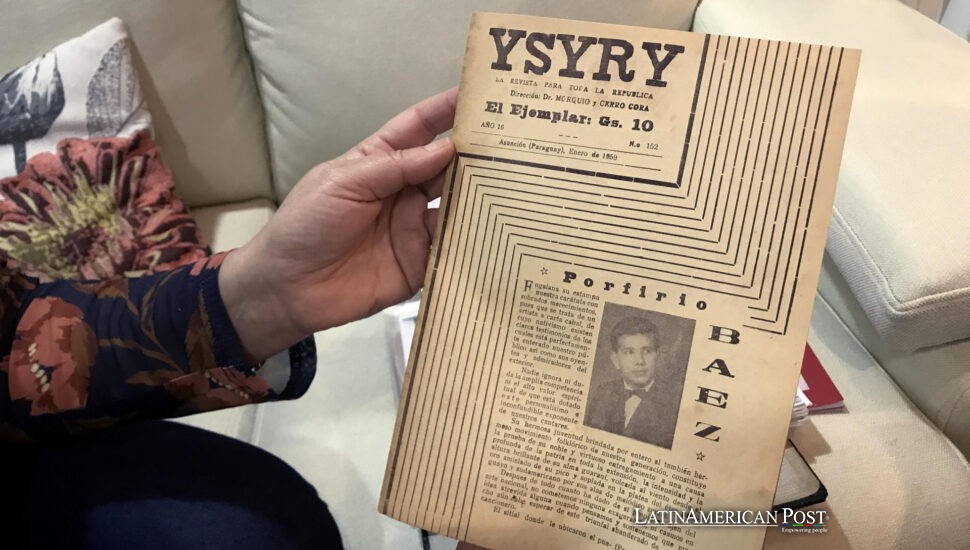

Long before hashtags and feeds, a modest cultural magazine called Ysyry—Guaraní for “running water” or “river”—quietly ferried poems through Paraguay’s literary landscape. From 1942 to 1995, it published nearly 20,000 pieces in Guaraní, Spanish, and the beloved blend of both, jopara. Then the river seemed to dry up. Its editor, José del Pilar Cantero Frutos, faded into memory, and a complete set of the magazine survived only in patched copies.

That survival turned dramatic in 2008, when U.S. Ambassador James Cason prepared to leave Paraguay. A woman—still unidentified—placed 271 pristine issues in his hands. “He was passionate about the Guaraní language and a lover of Paraguay,” recalled Alda Cardozo, national director of Fundación Paz Global, in remarks to EFE. “Whoever entrusted him with the magazines must have seen how much he loved Guaraní.”

Cason, who sang in Guaraní at festivals and embraced Paraguayan traditions, became the unlikely custodian of an entire era’s literary heartbeat. For years, fifteen thick binders of Ysyry sat in his home in the U.S.—safe, catalogued, but far from their homeland.

The ambassador and the suitcase

Eventually, a decision was made: the collection had to return to Paraguay. Cason, together with Thomas Field of the Global Peace Foundation, agreed that the magazines needed a new life. Field personally carried the fragile trove back to Asunción—”valija en mano,” suitcase in hand—ensuring the pages survived humidity, mishandling, and the risks of travel.

Since 2023, Fundación Paz Global and the Instituto Patria Soñada have worked to digitize and organize the collection for the Oremba’e virtual library—”what is ours” in Guaraní. Of the roughly 20,000 works, 14,000 have been prepared for the digital edition. To launch the project, the partners also produced the first print anthology, Che Ñe’ẽ, Che Purahéi—”My Word, My Song”—with 200 poems and songs spanning generations.

The anthology includes giants like Emiliano R. Fernández, Manuel Ortiz Guerrero, and Félix Giménez, as well as lesser-known names and amateur voices who contributed to Ysyry’s pages. That chorus of the famous and the forgotten gave the magazine its soul. “We wanted to give this collection the dignity and reach it deserves,” Cardozo told EFE, adding that the goal is also to spark curiosity among Paraguay’s youth, who now inhabit a literary ecosystem unimaginable when Ysyry was first printed.

Translating memory for the next generation

Rescuing the river meant more than scanning pages. It required translating the memory itself. “The richness of the material is immense,” explained María del Carmen Giménez, project director at Instituto Patria Soñada, in an interview with EFE. Her team of linguists adapted the orthography of 20th-century Guaraní to modern standards without stripping away its cadence or color. The aim was to invite today’s readers in, not lock them out behind archaic spellings.

The poems span Paraguay’s most tender and turbulent moments. They mourn the War of the Triple Alliance (1864–1870) and the Chaco War (1932–1935), register the ache of exile during Alfredo Stroessner’s dictatorship, and whisper of “auto-exile” by dissidents who stayed but lived in hiding. They flirt and tease in verses of picardía, praise mothers and hometowns, and offer lyrical tributes to fellow writers—proof that poetry itself became part of the nation’s civic fabric.

Giménez noted that recurring themes of family and belonging run like threads through the work. “It has been a very gratifying challenge to find so much in a collection so complete and so carefully guarded,” she said to EFE. Young women on her team have been particularly determined to stitch the archive into contemporary life. Their effort carries an irony: although a woman preserved the collection, only about fifty of the thousands of signed pieces bear a woman’s name. Making Ysyry accessible online, they hope, will help correct that imbalance in the future.

The mystery woman and the hope of return

Every great cultural rescue carries a mystery. In Ysyry’s case, it is the woman who handed the complete collection to Ambassador Cason in 2008. Curators believe she was a relative of editor Cantero Frutos; the pristine run and meticulous repairs suggest that she received deep personal care. But her identity remains unknown. “We hope she will appear and receive the recognition she deserves,” Cardozo and Giménez told EFE.

Until then, her anonymous gift frames the larger question Ysyry always asked: what does stewardship look like in a bilingual country where identities overlap like braided verses? The answer lies in the project’s name: Oremba’e—what is ours. By digitizing 14,000 works and publishing Che Ñe’ẽ, Che Purahéi, the partners are affirming that “ours” means Guaraní, Spanish, and jopara—not in rivalry but in harmony.

The rescue also shows how diaspora and diplomacy can unexpectedly safeguard culture. Cason’s passion meant the magazines were cherished, not forgotten. Field’s suitcase run treated them as living documents, not relics. And the careful editorial work in Asunción has turned them into a searchable river that schools, families, and scholars can now enter.

The first tributaries are already flowing: an anthology readers can hold and an online archive anyone can browse. In a country where language is both inheritance and invention, Ysyry’s return reminds Paraguayans that archives are not mausoleums but rehearsals—where words that once consoled, teased, and rallied can do so again.

Also Read: Tiwanaku Temple Hiding in Plain Sight Rewrites Maps in Bolivia

If the unknown woman one day steps forward, she will see more than a rescued magazine. She will see a community waiting at the riverbank, ready to be carried forward by words once lost and now found again.