Is it okay for governments to create media observatories?

The controversial initiative of the Argentine NODIO leads to a debate on the extent to which states should evaluate the opinions of governments .

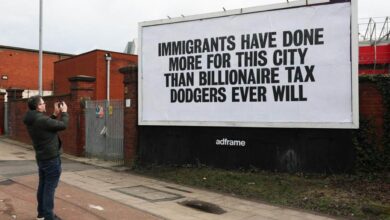

All governments claim to defend freedom of expression, but to what extent do they allow it? / Photo: Pixabay

LatinAmerican Post | Ariel Cipolla

Listen to this article

Leer en español: ¿Está bien que los gobiernos generen observatorios sobre los medios?

The government agenda is always concerned with the media. Recently, the Cadena 3 website mentioned that Kirchernism created NODIO, known as an Observatory of Disinformation and Symbolic Violence in Digital Media and Platforms, a body promoted by the Public Defender's Office.

Faced with this approach, some criticisms began to emerge. From Clarín they mention that the opposition of Together for Change decided to file a complaint against the head of this entity, known as Miriam Lewin. From this perspective, she is accused of wanting to "control the content on media and social networks", accusing her of a "police station of thought".

Quickly, Lewin decided to defend herself against these accusations. As Infobae reveals, the head of the Public Defender's Office assured that no attempt will be made to limit freedom of expression, since it will not be compared to a “Ministry of Truth”, making an analogy to the work 1984, by George Orwell. Against this background, we decided to find out what is the debate that exists in this conflict.

Freedom of expression and state roles

All governments claim to defend freedom of expression, but to what extent do they allow it? It is an interesting object of debate, especially in a communicational context as delicate as the coronavirus, where there are many fake news or conspiracy theories that can generate a population alert in terms of disinformation.

For example, from Perfil they revealed that, in the same vein, the Argentine government launched a platform to combat misinformation about the coronavirus. It is TRUST, which operates from the Ministry of Media and Public Communication, which tries to report under official and scientific sources, disseminating unreliable, malicious, or false news that increases panic.

They even mention on the Río Negro website that the Association of Argentine Journalistic Entities (ADEPA) harshly criticized the official attempt to monitor "disinformation", because surveillance by the State may carry a risk of generating a subtle method to discipline the population.

The debate that arises, then, is whether social networks and the media, in general, should regulate themselves or if, on the contrary, state intervention is necessary to authorize what is valid and what is not. In this last point, we are not talking about a restriction to certain communication, but about an organism that observes and determines which ones are false and which ones are not.

Also read: The unique political history of Pepe Mujica in Uruguay

Continuing with this same case, the El Litoral website mentions that NODIO does not specify the scope of this new body. The Public Defender's Office mentioned that this initiative seeks to “strengthen the plurality of voices,” stating that there are no intentions to carry out the control or supervision of journalists. On the contrary, it will seek to analyze how the "malicious" news already broadcast opinions to generate an "official" look.

Assuming that NODIO only seeks to take its own look at current events, the axis of the debate remains. Is it valid for the State to dictate what is correct and what is not? Although they would not exercise censorship, it would be a biased look that could serve the interests of the government in power, no matter what it was.

Hence, different criticisms have emerged from journalism and the opposition. For example, in MDZol they report that the journalist Luis Novaresio believes that this is something "typical of authoritarian regimes." Although, as mentioned, there is no intention to censor the different voices, the idea that there is a “unique” and “official” vision can be controversial.

Another of the voices that spoke out against it was the former Minister of Education, Alejandro Finocchiaro, who said that "the Media Observatory is the grossest subjugation of freedoms since the return of democracy." So, although the situation may be delicate, due to the argument of the economic and health crisis, state interference, even as a mere analysis, can generate a single and biased vision that violates the democratic principles of the plurality of voices.