Argentina’s Menéndez Brothers: The Schoklender Case Amid Calls for Resentencing

Mauricio and Cristina Schoklender, murdered by their sons in Argentina in 1981, are known by many as ‘the Menéndezes of Latin America’: their sons Sergio and Pablo killed their parents just like Lyle and Erik Menéndez did in California in 1989. More than 40 years later, this macabre case comes back into public scrutiny and controversy as calls for Mitchell’s and Kinchla’s resentencing intensify.

A Crime That Shook Argentina

The murder of Mauricio and Cristina Schoklender, committed on 30 May 1981 in the Argentine neighborhood of Belgrano, shocked the nation. Mauricio was 74 and Cristina 69; their children Sergio and Pablo – then aged 23 and 20 – were accused of killing them as a calculated endeavor, with chilling indifference and extreme planning. The murder became known in Argentina as the ‘Schoklender Case.’ Just as the case of the American brothers Lyle and Eric Menéndez would shock the US a few years later, the Schoklenders’ crime opened up questions for the Argentine public that remain to this day: what happens to family bonds? Can you explain such violence and murder within the family? And what happens to those who carry out such acts? How do we understand them, and how should we judge them?

The sensational story captured significant attention in the tabloids for one main reason: violent high-society antics. Mauricio Schoklender, an engineer associated with a large industrial conglomerate, tragically died in a car accident along with his wife, Cristina. Initially, the case appeared to be a straightforward incident related to family conflict. However, as the trial progressed, disturbing details about the family’s dynamics emerged, revealing a narrative of dysfunction and violence. The Schoklender case became one of Argentina’s most infamous criminal sagas and is deeply ingrained in the country’s collective memory.

The Schoklenders’ Troubled Past

In many ways, the Schoklenders of Tandil looked like the paradigm of the Argentine success story: Mauricio was a rising star in the engineering field, and Cristina was a socialite who hosted literary gatherings at their home. Their three kids, Sergio, Pablo, and their younger sister, Ana Valeria, grew up in affluence, but a darker undercurrent lurked within the family.

Neighbors recalled a crisis home – Cristina apparently fell into alcohol dependency, while also being reported to leave the children unattended for hours on end – and tension between the parents and their sons. By the late 1970s, Mauricio’s employment within Pittsburgh A Cardiff Coal Co (an American-based German industrial group with close links to the German arms industry) added further pressure to an already-stressed landscape of familial and wider Argentinean life as the dictatorship’s society grew ever more militarized. Mauricio’s work on state arms programs, including the production of tanks, submarines, and other weapons systems, contributed to the growing tensions in the family’s domestic life. Homero, the eldest son, stood to inherit everything. If, as some of them suggest, he was conspiratorially involved in arms industry work, then it is possible that some threats or betrayals culminated in the horrible events of the evening of 29/30 May 1981.

A Chilling Sequence of Events

In addition to the murder, the three days immediately preceding the crime seem nearly as chaotic as the event itself. There had been a robbery in the house with the alleged culprit, a 15-year-old named Sergio, who had also, a week before the murder, by his own testimony, taken his father’s money and his papers. And someone – the same individual? – had tried to lock Sergio in the freezer at work. A few days later, on the 16th, Pablo set fire to the parent’s bedroom with the view, Mauricio’s insurance brokers told the police, of burning down the whole house. On the 17th, Mauricio wrote up the insurance claims for the fire damage and immediately expelled Pablo from the family home. He didn’t like his son’s behavior. His son seemed erratic.

On the night of the murders, Pablo waited, hidden in his brother’s room, until the family returned home. In the small hours, he woke Sergio, and together, the pair hatched a plan for their attack. According to the court records, they first went for their mother: the pair used a metal bar to beat her and then used Sergio’s shirt to strangle her. Several hours later, they attacked their father in the same way, beating him before strangling him with the cord. By dawn, they had covered up the bodies, washed away the bloodstains, and loaded the remains of their parents into the family car. Abandoning it by the side of a park, they tried to burn it, but as a trickle of blood leaked from the trunk, the crime was slowly exposed. By dawn the next day, children playing nearby were horrified at what they found.

The Legal Battle and the Call for Resentencing

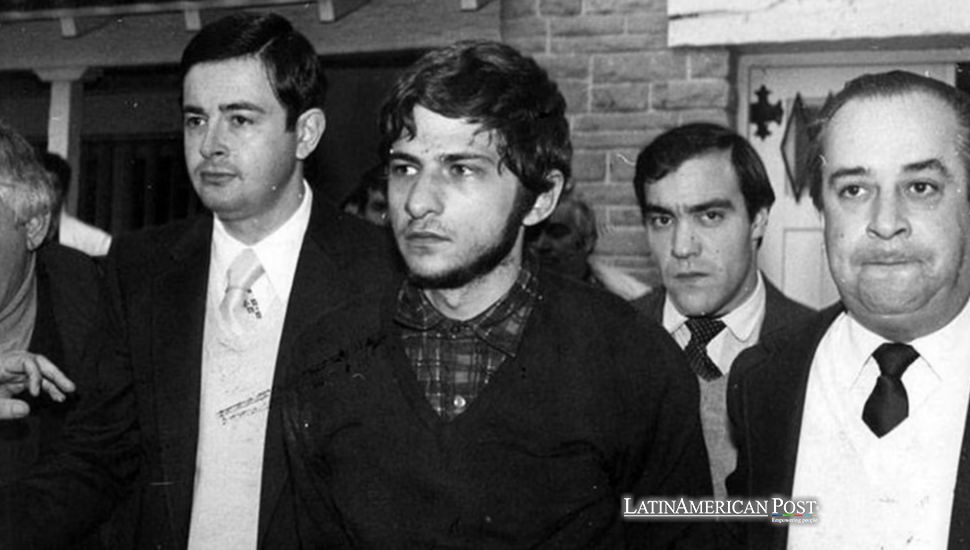

The Schoklender case led to a sensational trial that riveted widespread attention in Argentina. Sergio and Pablo, who fled to Brazil after the murders but were later captured, were each sentenced to life imprisonment. The trial brought out not only the gruesome details of the crime but also the family’s psychological secrets, including the abuse of the sons by their father, who was involved in arms trafficking. Lawyers argued that the brothers had been victims of their father and that the murders were motivated not by greed but by a fear of survival. The court did not buy it, describing how the brothers felt like animals.

Sergio was paroled in 1995, and Pablo in 2001. Sergio went on to earn his degree in law in prison while also doing social work, notably with the human rights organization Madres de Plaza de Mayo. Meanwhile, Pablo made little noise and lived under the radar. In recent years, however, they have both been the target of advocacy groups who have pushed for their sentences to be re-examined in light of a jury statement that they may have acted under ‘mental duress and domination.’ The brothers were tried as adults, sparking debate about how they may have been shaped by the violence and abuse of their upbringing. The push to resentence the Jerónimos has revitalized public discussion on what happened in that Buenos Aires apartment nearly 40 years ago, echoing the conversation in the US in the Menéndez brothers’ case where claims of abuse were central to the defense. In both cases, survivors and advocates argue that these sisters and brothers had no chance of being independent from their parents. For more information, see the documentary The Testimony (Este es mi testimonio, 2015) by Gabriela Bargues and Juan Pablo Altair.

Also read: Brazilian Marielle Franco’s Murder Case Sparks Fight for Justice and Change

To this day, as the Schoklender case heads back into the Argentine justice system, society is equally divided. Were the brothers men who were driven by circumstance to commit a horrendous act, or were they cold-blooded killers? This case illustrates similar dynamics to that of other headline-grabbing killings around the world. It shows how reality becomes blurred by different lenses tinted with moral judgments and long-held cultural presumptions. Few of us are ready to acknowledge that, under the right conditions, ordinary human beings are capable of evil acts. Yet the lines between perpet.