“El Ratón” Talks: Will El Chapo’s Son Break the Cartel Code in a Chicago Courtroom?

A son of Mexico’s most notorious drug lord sits in a Chicago courtroom, poised to trade secrets for time, while in Sinaloa, gunmen reload, politicians brace, and an entire nation wonders: will El Ratón squeal, and who will die for it?

The Mouse in the Cage

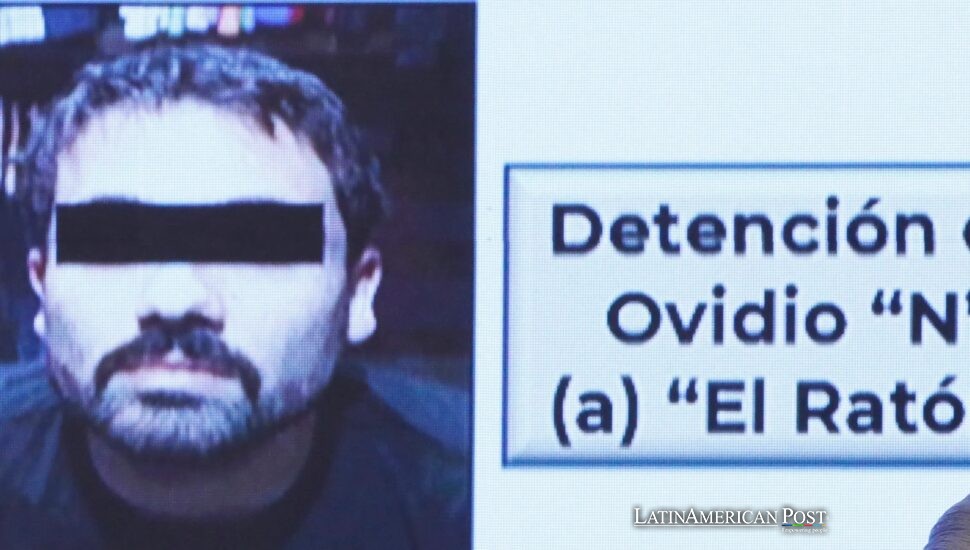

Not long ago, Ovidio Guzmán López—better known as El Ratón—was one of the most wanted fugitives in the Western Hemisphere. Now he’s just another inmate in an orange jumpsuit, shuffling into a cold Chicago courtroom, flanked by U.S. marshals. The son of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, founder of Mexico’s infamous Sinaloa Cartel, has pleaded guilty to trafficking fentanyl into the United States. But more than punishment, what’s now at stake is information—dangerous, valuable, and potentially explosive information.

Everyone is watching. Prosecutors. Journalists. Academics. Hitmen. Suppose Guzmán decides to cooperate with U.S. authorities. In that case, the consequences won’t just echo through federal sentencing guidelines—they could ignite new wars, collapse protection networks, and rattle the Mexican state to its core.

“He has two kinds of secrets,” said Vanda Felbab-Brown, a scholar at the Brookings Institution who studies organized crime. “The first is operational—where the labs are, how the shipments move, who manages the crypto wallets. But the second tier, the political tier, that’s what could blow this wide open.”

Naming rival drug traffickers won’t change much. But if El Ratón starts naming officials—local police, army commanders, even cabinet-level insiders—he could unravel the very protection rackets that keep cartels alive. And unlike a firefight in the Sierra Madre, this war will be fought on the record, in air-conditioned silence, under oath.

Civil War in Sinaloa

To understand the stakes, you have to understand the cracks within the cartel. For twenty years, the Sinaloa Cartel ran more like a confederation than a dictatorship. On one side were the old-school loyalists under Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada, the invisible man of the drug trade. On the other hand, the flashy, reckless sons of El Chapo—collectively known as Los Chapitos.

The peace is held through marriages, baptisms, and tradition. El Mayo is even a godfather to several Guzmán grandchildren. But the alliance soured as the Chapitos embraced Instagram fame and turned their father’s empire into a more volatile, less disciplined machine.

The final split came last July, when another Guzmán brother was quietly extradited to the U.S.—on a private jet allegedly arranged by Zambada’s people. Felbab-Brown called it “borderline kidnapping.” Others called it a declaration of war.

Since then, Sinaloa has been bleeding. More than a thousand bodies have surfaced in morgues across the state since last September, the result of turf wars between the Chapitos, the Mayitos, and the rising power of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG). Rumors of shifting alliances only add gasoline. Falko Ernst, a senior analyst at International Crisis Group, believes whispers of a CJNG-Mayitos pact may be both honest and strategic: “Each side leaks just enough to raise the stakes.”

If Ovidio starts naming names in that courtroom, don’t expect peace. Expect retaliation.

EFE@Cesar Contreras

What’s a Snitch Worth?

In U.S. courtrooms, truth is a commodity—and the DEA pays in years, not dollars. Federal sentencing guidelines for Guzmán’s crimes start at ten years and run to life. But with “substantial assistance,” defendants routinely cut those numbers in half.

David Skarbek, a sociologist at Brown University who studies prison economies, says the price of leniency is novelty. “They don’t want what they already know,” he explains. “They want new proof that links cartel operations to Mexican institutions—politicians, colonels, finance directors.”

The logic is brutal: exposing rival capos is good. Exposing corrupt officials is better. Breaking the myth that the state is neutral? Priceless.

But Guzmán isn’t alone. If he talks, El Mayo’s faction may hit back—not with bullets, but with its cooperation. The result? A mutual snitch war, where both sides gamble on burning each other to minimize prison time.

There’s precedent. When the Gulf Cartel started cooperating with U.S. agents in the early 2010s, it triggered a bloody collapse of Los Zetas. The lesson? Cutting off cartel heads doesn’t end the violence. It spreads it.

What Justice Can—and Can’t—Fix

Let’s say Guzmán spills it all. Let’s say prosecutors get everything—names, labs, bank accounts, even links to Mexico’s political elite. Will it matter?

To some extent, yes. It’s leverage. It’s bargaining power in Washington, where fentanyl policy has become politically radioactive. It’s a way to push Mexico on extraditions, on border patrol, on financial crackdowns. And for a fleeting moment, it might disrupt Sinaloa’s internal structure.

But it won’t stop the killing.

Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera, professor at George Mason University, says the real solution isn’t courtroom deals. It’s structural. “You need policing reform. Economic alternatives. Community investment. Otherwise, this is just a reshuffle.”

People in Culiacán already know what’s coming: short-term chaos, revenge killings, power grabs. They’ve seen it before. Every time a kingpin falls, there’s a roar of violence before the next one rises.

Still, the significance of Guzmán’s plea shouldn’t be underestimated. It marks a shift. Once mythologized in narcocorridos, El Chapo’s children are now negotiating with the very government they used to defy. Far from the mountains and the safehouses, in a city better known for deep-dish pizza than drug wars, the story of Sinaloa’s empire may be rewritten not by bullets, but by whispers.

Credit: Original reporting by EFE, with expert commentary from Vanda Felbab-Brown (Brookings), Peter Reuter (University of Maryland), David Skarbek (Brown University), Falko Ernst (International Crisis Group), and Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera (George Mason University).