Latin America’s Quiet Rebellion Against Churches While Clinging To Faith

Across Latin America, Catholic cathedrals still dominate skylines, yet data reveal surging Protestant movements, rising religious “nones,” and deepening spirituality—an unexpected quiet religious revolution reshaping politics, culture and identity from Mexico to Chile, as research reported by The Conversation shows.

Institutions Shrink, Devotion Refuses to Disappear

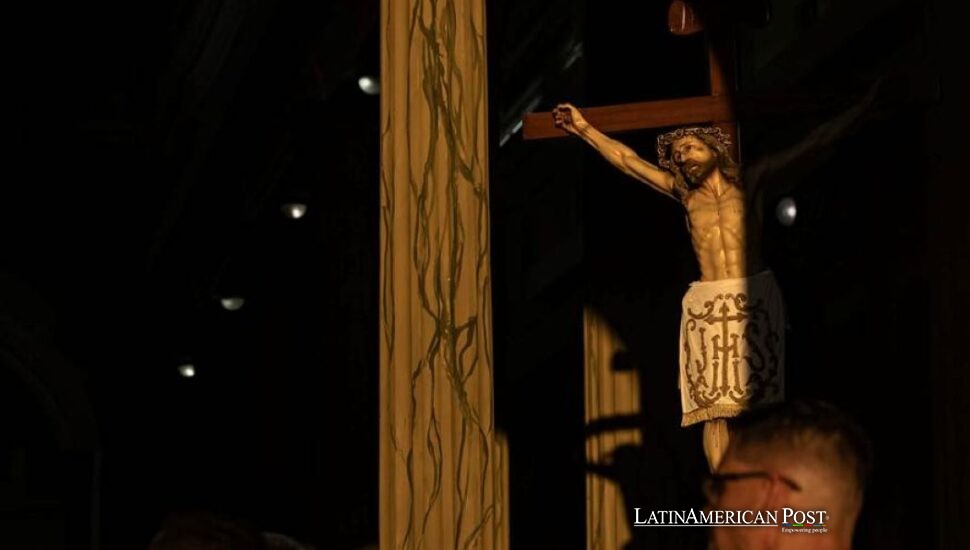

For centuries, the story seemed settled: Latin America was Catholic, almost by definition. From the silver altars of Cuzco to the crowded processions of Guadalajara, Catholicism stitched together empire, nation-building and everyday life. The region’s status as a religious stronghold appeared confirmed in 2013, when Jorge Mario Bergoglio of Argentina—now known worldwide as Pope Francis—became the first Latin American to lead the global Church. Today, more than 575 million Catholics live in Latin America, roughly 40% of all Catholics on Earth, far outpacing Europe and Africa, which each harbor about 20% of the world’s Catholic population. Yet beneath those imposing numbers, the ground is moving.

The first tremor came from Protestant and especially Pentecostal churches. In 1970, only about 4% of Latin Americans identified as Protestant. By 2014, that share had climbed to almost 20%, mirroring decades of scholarship in journals such as Latin American Research Review and Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion that trace how Pentecostalism flourished in urban peripheries, amid poverty, crime and fragile democracies. But a second, quieter shift unfolded at the same time. A rising share of Latin Americans began leaving institutional religion altogether. In 2014, around 8% of the population claimed no religion, twice the proportion raised without any religious identity—evidence that many were walking away as adults, not simply growing up outside faith traditions.

This undercurrent is now far clearer thanks to new analysis of the AmericasBarometer survey, first highlighted in September 2025 in The Conversation. Drawing on two decades of data from more than 220,000 respondents in 17 Latin American countries, the survey’s standardized questions about religion and politics offer a rare longitudinal view. The share of people reporting no religious affiliation rose from 7% in 2004 to over 18% in 2023. In 15 of the 17 countries, the unaffiliated share increased; in seven, it more than doubled. On average, about 21% of people in South America now say they have no religious affiliation, compared with 13% in Mexico and Central America. Uruguay, Chile and Argentina stand out as the least religious, while Guatemala, Peru and Paraguay remain bastions of traditional affiliation, with fewer than 9% unaffiliated. For a region long seen as the Catholic “backyard” of the West, these are seismic numbers.

A Generational Earthquake in the Latin American Pew

Institutional decline becomes even clearer when researchers look at churchgoing. From 2008 to 2023, the proportion of Latin Americans attending religious services at least once a month fell from 67% to 60%. Over the same period, those who say they never attend increased from 18% to 25%. The generational gradient is unmistakable. Among people born in the 1940s, just over half report going to church regularly. Each subsequent generation attends less often, dropping to only 35% among those born in the 1990s. Religious affiliation follows the same downward slope: each younger cohort is less likely to claim a formal faith than the one before it.

These patterns resonate with wider Latin American realities. Younger adults came of age after authoritarian regimes, amid neoliberal reforms, social media and recurring corruption scandals that eroded trust in institutions of all kinds—from political parties to courts and, inevitably, churches. Academic work in journals like Sociology of Religion has long argued that institutional credibility is a fragile resource. In Latin America, where the Church has alternated between defending the poor through liberation theology and colliding with progressive agendas on gender and sexuality, young people often perceive religious hierarchies as just one more power structure to question. Yet this does not mean they are abandoning belief itself.

That distinction becomes clear when researchers shift from counting mass attendance to asking how important religion is in people’s daily lives. In 2010, about 85% of Latin Americans in the 17 countries analyzed said religion was important to their everyday existence. Around 60% considered it “very” important, and 25% “somewhat” important. By 2023, the “somewhat” camp had shrunk to 19%, while the “very important” group climbed to 64%. In other words, as affiliation and attendance drift downward, the intensity of personal religiosity is actually rising. This is not a simple story of secularization; it is a reconfiguration in which formal boundaries weaken even as inner conviction strengthens.

Believing Without Belonging, Latin American Style

Generational data complicate easy assumptions that older people are simply “more religious.” Taken at face value, older cohorts do report higher levels of importance. In 2023, about 68% of those born in the 1970s said religion was “very important,” compared with 60% among those born in the 1990s. Yet when people are compared at the same age, the pattern flips. At age 30, roughly 55% of those born in the 1970s rated religion as “very important.” Among those born in the 1980s, that figure rises to 59%; among those born in the 1990s, to 62%. If this trend holds, younger generations could ultimately display stronger personal religious commitment than their elders, even as they avoid institutional labels.

The contrast with Europe and the United States is stark. In much of Western Europe, long-term data show institutional decline and erosion of belief moving hand in hand, a pattern widely discussed in journals such as European Sociological Review and Social Compass. By comparison, Latin America is full of “believers without belonging.” Fully 86% of religiously unaffiliated Latin Americans say they believe in God or a higher power. That figure stands at about 30% for the unaffiliated in Europe, and 69% in the United States. Significant shares of Latin America’s unaffiliated also affirm belief in angels, miracles and even the possibility that Jesus will return to Earth within their lifetime. Dropping a church label or skipping Sunday services, in this context, does not mean walking away from the sacred.

This paradox is rooted in the region’s long, messy religious history. Since the 16th century, Latin America has been a laboratory of spiritual mixing, where Indigenous cosmologies, African diasporic traditions and Iberian Catholicism collided. Priests were often scarce, especially in rural zones and marginalized barrios, so religious life grew around home altars, neighborhood processions, lay leaders and local devotions to saints and Marian images. Scholars of “popular Catholicism” and syncretism, writing in outlets like Latin American Research Review, have documented how families negotiated belief largely outside rigid ecclesiastical control. That legacy lives on in prayer circles in São Paulo apartment blocks, healing services in the hills of Guatemala, and WhatsApp chains of miracles and novenas shared by migrants in Los Angeles and Madrid.

These new numbers from AmericasBarometer therefore challenge the standard toolkit that scholars built largely on Western European experience, where affiliation and church attendance serve as the main barometers of religious vitality. In Latin America, those indicators can be misleading. A young woman in Lima may rarely set foot in a parish, distrust bishops, and still cross herself before boarding a bus, consult a Pentecostal pastor about a sick relative, and believe fervently that God has a plan for her life. She is invisible in statistics that focus only on institutional loyalty, yet central to understanding how faith actually works on the ground.

Politically, this fragmented religious decline has profound implications. Analysts tempted to equate lower church attendance with automatic secularization risk misreading voter behavior on issues such as abortion, LGBTQ+ rights, corruption or environmental protection. Personal spirituality—shaped by Catholic symbols, Pentecostal moral language and Indigenous reverence for land—continues to inform how millions interpret injustice and hope. As the region’s democracies struggle with inequality, violence and mistrust, religious institutions may lose their monopoly on moral authority, but the language of faith remains a powerful currency in campaigns, social movements and everyday life.

In short, Latin America is not simply drifting toward a European-style secular future. It is carving out something more complex: a landscape where churches lose members, religious labels fade, but belief in the transcendent stays stubbornly alive, and in some cases grows sharper. The data illuminated by The Conversation and grounded in AmericasBarometer remind us that here, faith is not confined to pews or parish rolls. It thrives in kitchens, streets and digital networks—quietly rewriting what it means to be a believer in the twenty‑first century.

Also Read: Brazilian Modernist Portinari and Matisse Heist Shocks São Paulo Library