Latin Heartbeat Muffled as Washington Crackdowns Silence Mount Pleasant Streets

At noon in Washington’s Mount Pleasant, the cafés and pupuserías that once spilled music and chatter into the streets sit nearly empty. National Guard troops and a surge of federal agents now patrol the neighborhood, deepening fear of deportation and muting the daily rhythm of this Latin enclave.

A banner, a silence, and a community on edge

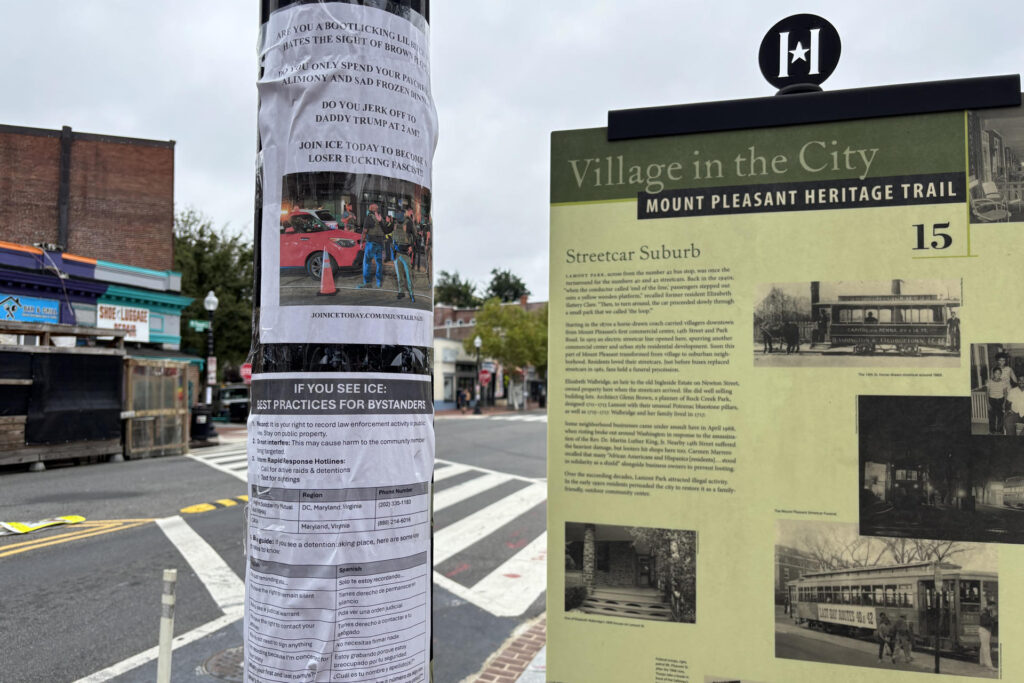

The pastel facades of Mount Pleasant’s row houses still gleam in the summer sun, but the soundtrack has vanished. Patios that once pulsed with bachata and laughter are deserted; inside, a single customer lingers over a coffee. In the main square, a banner hangs in Spanish: “No a las deportaciones en Mount Pleasant. No a la Migra.”

Since President Donald Trump declared a Public Security Emergency and deployed the National Guard in the capital, residents say a hush has spread through “Little El Salvador,” a neighborhood shaped by decades of Central American migration. Fear here is not abstract. Federal authorities have flooded the area with FBI, DEA, and ICE agents. Attorney General Pam Bondi announced that 630 arrests have already been made. Activists counter that immigration sweeps are embedded in the broader operation, pulling in undocumented neighbors who now vanish without warning. For families who thought they had escaped the displacements of war and poverty, the sense of being hunted has returned.

‘The people are afraid’: voices behind closed doors.

Across storefronts and apartments, routine has been rewritten by fear. A Salvadoran woman who has worked in a local restaurant for nearly twenty years told EFE she now leaves home only for her shift and rushes back before dark. She drives for a ride-hailing service, holds legal residency and a work permit—yet she has stopped taking rides entirely. “This is only against us,” she told EFE, asking not to be named. “You don’t see Ethiopians, Chinese, or others afraid. They are coming for Hispanics.”

At the same bar, another Salvadoran—its only midday patron—kept glancing at the door. “People are terrified,” he said to EFE. “The psychological pressure is enormous because you see it in the street, and then you see it on social media.”

Even the flash of police lights has become a trigger. “Every time I see the lights, I feel fear about what could happen,” he admitted. Parents whisper contingency plans. The waitress worries most about her toddler: “I’m afraid I’ll be detained on my way to work—what would happen to my three-year-old?”

Soccer fields and church steps, once gathering points, are quiet. Families order groceries online, keep curtains drawn, and trade updates through encrypted chats rather than neighborhood meetings. In Mount Pleasant, fear has rewritten the map of everyday life.

Restaurants are counting empty seats and missing workers.

The economic aftershocks are everywhere. A manager at a chicken restaurant said suppliers now call to ask why orders have plummeted. “We don’t have customers to sell the product to,” he told EFE. Delivery apps aren’t filling the gap. Many couriers, primarily Latin American immigrants, have quit out of fear. Others who stayed have been detained. “We’ve reduced staff shifts because there’s no work,” the manager explained.

More painful than empty tables are missing colleagues. One line cook stopped showing up. A co-worker later saw a TikTok clip that appeared to show him being arrested by immigration agents. The restaurant hasn’t heard from him since. Down the block, a bartender surveyed the barren lunch rush. “People don’t want to be seen,” she told EFE. “They pay cash, they don’t linger.”

For business owners who clawed their way through the pandemic, this new emptiness is different: not government-ordered closures, but a vanishing clientele. Every cut shift means fewer paychecks for rent, fewer remittances sent to family abroad, and fewer tips saved for a child’s school supplies. Cash registers fall silent—and so do the dreams they once bankrolled.

Hoping the month ends, bracing for an extension

Crime is still a political lightning rod citywide, but federal data show rates at their lowest in three decades. Still, the security perimeter here grows tighter: more uniforms, more lights, more eyes. The White House initially said the operation would last a month. Trump has already signaled he wants to extend it, a move requiring congressional approval, where he holds a majority.

In Mount Pleasant, residents count the days in uneasy hope. “They said it would last a month,” an older woman said to EFE as she hurried home with groceries. “I pray to God it’s quick and that everything goes well.”

For now, the familiar rhythms of the neighborhood—merengue drifting from open windows, teens spilling from bakeries, pupusas frying for dinner crowds—are muted. Civic energy has shifted to quiet mutual aid: neighbors walking one another’s children to daycare, small businesses fronting wages, church deacons making late-night calls to confirm who got home.

Also Read: Latin America Battles Narcos Container Hacks as Insiders Sell Routes

The banner in the square is more than a protest. It is a plea and a warning. No, the deportations in Mount Pleasant speak not just for one enclave but for the fragile trust between communities and the city that surrounds them. Public safety and public trust rise or fall together. Mount Pleasant knows which path it needs. It waits to see if the city—and the country—will choose the same.