Mengele’s Unwanted Bones: A Haunting Relic Boxed Away in Brazil’s Medical Vault

In São Paulo’s bustling city center, locked away on a discreet shelf, lie the forgotten remains of Josef Mengele — the notorious Nazi physician who evaded capture for decades. As the world nears the 80th anniversary of WWII’s end, his bones rest in plastic obscurity.

Forgotten Bones in São Paulo

Eight decades after the collapse of the Third Reich, the skeletal remains of Josef Mengele, infamous for his brutal human experiments at Auschwitz, remain boxed and unclaimed in Brazil. In an interview with EFE, the São Paulo Public Security Department sources revealed that his bones are “stored individually, labeled with a specific number” in the city’s Legal Medical Institute (IML).

Brazilian law strictly governs how unidentified or unclaimed bodies should be handled, which puts Mengele’s remains in limbo. Because none of his family members has ever requested their release, the IML is legally barred from discarding or disposing of them. A representative from São Paulo’s Technical-Scientific Police told EFE that the situation is unprecedented: “He is a corpse with no legal claimant, and our legislation prevents us from taking any further action.”

For its part, the Jewish community is also avoiding any suggestion of exhuming or relocating Mengele’s remains. “We have no interest in moving them,” explained Ricardo Berkiensztat, executive president of the Israeli Federation of São Paulo, in a conversation with EFE. We believe that the less attention paid to this matter, the better, so it does not become a site of twisted veneration.”

What remains in the IML’s storage room is not just an inconvenient skeleton but also a symbol of an evil that once terrorized Europe. Mengele—Auschwitz’s so-called “Angel of Death”—spent three decades in hiding. Even after his drowning in 1979, his identity stayed concealed until a multi-nation investigation and exhumation revealed the truth.

Unrepentant War Criminal

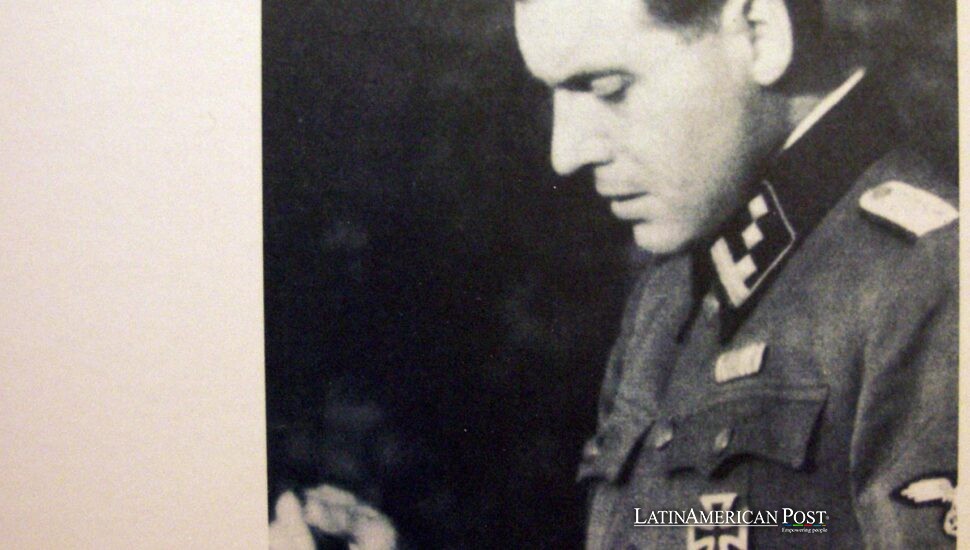

Born in 1911, Mengele escaped Europe following the fall of Nazi Germany, first fleeing to Argentina. As Nazi hunters and international authorities closed in—particularly Israel’s Mossad—he hopped borders, eventually settling in Brazil in the late 1950s. Mengele used aliases like Helmut Gregor, Peter Hochbichler, and Wolfgang Gerhard. This helped him avoid being found. He lived quietly with local families.

In Brazil, he lived a simple life. He read, wrote, tended a garden next to, and talked to a few close friends. This was different from the terrible actions he directed at Auschwitz. According to official documents and personal letters cited by Brazilian journalist Betina Anton in her award-winning book Baviera Tropical, Mengele quietly administered farmland, looked after his dogs, and even shared meals with unsuspecting acquaintances. During the EFE interview, Anton said he relegated Auschwitz to oblivion. He showed neither guilt nor remorse. Anton stated, “He committed atrocities in countless numbers, yet he never spoke about them. The way he erases the brutal past from the conversation is frightening.”

In Auschwitz itself—officially known as Auschwitz II-Birkenau—Mengele was notorious for exploiting inmates in pseudo-scientific “research.” Twins and pregnant women were among the recorded victims – he used to torture them in a system to examine his racial theories. Testimonies from several who survived, including Ruth Elias, a Czech who survived, explain his actions to stop mothers from breastfeeding. That action changed newborns into subjects for experiments about starvation.

These crimes, along with many others, ensured Mengele’s infamy. After WWII, he navigated to Genoa and sailed for Argentina in 1949 under the Perón regime. Fearing capture, he crossed Paraguay in subsequent years before heading to Brazil. His final refuge proved lethal when he drowned at the age of 67 while swimming off a beach in Bertioga, São Paulo.

The remainder of the planet did not understand his death before 1985. During that year, a shared effort among intelligence agencies from the United States, West Germany, and Israel found essential evidence. It was located in a letter directed to a neo-Nazi boss in prison. By following that thread, investigators traced Mengele’s false burial name, Wolfgang Gerhard, and exhumed his body from a cemetery in Embu das Artes, 25 kilometers from São Paulo.

A Hushed Brazilian Legacy

A global stir occurred in 1985 because of the exhumation. Several countries sent forensic experts, who spent months confirming the skeleton’s identity. Dental records were analyzed, bone characteristics were analyzed, and genetic testing was performed. With this, they established a 99.997 % probability that the remains belonged to Mengele. With that level of certainty, any doubt dissipated, but new questions arose: Who should take custody of these bones, and what moral or legal obligations come into play?

Brazilian authorities found no direct relatives willing to claim the remains, which left legal experts pondering how best to handle the relics of one of history’s most notorious war criminals. Under normal circumstances, unclaimed remains might be donated for medical research or quietly cremated after due diligence. However, the final decision remains stalled because Mengele’s case is fraught with gray areas in the legal system.

Betina Anton’s Baviera Tropical, lauded with Brazil’s prestigious Jabuti Prize, adds depth to the perplexing narrative. In her research, she unearthed details about the families that sheltered Mengele and discovered how easily he slipped into daily routines. Speaking with EFE, Anton confessed a personal connection: “One of my childhood teachers was among those who hid him. That story never left my mind.”

Such revelations underscore how effectively Mengele wove himself into the fabric of specific local communities, even forging friendships. But none of these acquaintances appear keen to keep his memory alive. Any reference to him causes unease and rejection. This outcome means the feared Angel of Death is left alone in death.

At the same time, Jewish organizations maintain a careful separation. Ricardo Berkiensztat emphasizes the importance of preventing Mengele’s body from becoming a repulsive memorial for radical groups. “It’s far preferable to let him remain forgotten,” he reiterated to EFE, suggesting that any spectacle surrounding the bones might create new problems—such as fueling racist or neo-Nazi sentiment.

Thus, the bones stay confined within their plastic boxes at the IML, meticulously tagged with numeric labels. Nothing distinguishes them from other unclaimed skeletons except for the dark historical weight they carry. Mengele’s grave remains officially undetermined. This serves as a distinct reminder about difficult moral questions related to men’s bodies. Those men’s deeds formed some of the most terrible moments in human history.

Beyond the cold, impersonal corridors of that São Paulo institute, the memory of Mengele lingers primarily as a warning from history: monstrous acts can sometimes slip away into quiet corners, obscured by alias after alias or by decades of denial. Yet the truth, once uncovered, remains incontrovertible. In the end, the man who once wielded absolute power over life and death in Auschwitz lies in oblivion—sealed in plastic, unclaimed, and largely forgotten.

Also Read: Historic New Chile Excavation Sparks Hope for Dictatorship Victims

In an era that marks 80 years since the defeat of Nazi Germany, the story of Mengele’s skeleton in Brazil resonates with a resonance that spans far beyond forensics. It speaks to the moral complexities of closure, justice, and remembrance—a haunting testament to what happens when the unthinkable slips into anonymity, leaving only hollow bones and even hollower justifications. The remains may be inert, but they remind us that some legacies can never be entirely laid to rest.