Peru’s Vladimiro Montesinos Sentenced for Role in 1992 Pativilca Massacre of Rebel Suspects

Vladimiro Montesinos, intelligence chief under Peru’s Alberto Fujimori, received a nearly 20-year prison sentence for orchestrating the 1992 Pativilca massacre, where six farmers suspected of rebel ties were executed. Already imprisoned for previous crimes, Montesinos’s guilty plea for the homicide and forced disappearance of these individuals adds another dark chapter to his controversial legacy.

Montesinos and Peru’s Turbulent Past

In the annals of Peru’s turbulent history, few names evoke the sinister legacy of the 1990s as powerfully as Vladimiro Montesinos, the intelligence chief under President Alberto Fujimori. On a recent Wednesday, Montesinos was sentenced to 19 years and eight months in prison for his involvement in the 1992 massacre of six farmers in central Peru, accused of being rebel sympathizers. This sentencing marks yet another chapter in the dark saga of a man who once wielded immense power behind the scenes of Fujimori’s government.

Montesinos’s journey to infamy began well before his ascension as Peru’s spymaster. A former military officer and a lawyer known for representing drug traffickers in the 1980s, his path took a decisive turn when Fujimori came to power in 1990. Montesinos was appointed as the intelligence chief, a role in which he would orchestrate some of the most egregious human rights violations in recent Peruvian history.

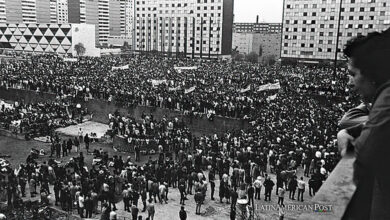

The town of Pativilca, located in the heart of Peru, became the site of one of these atrocities in January 1992. Soldiers, acting under orders from Montesinos, forcibly removed six farmers from their homes in the dead of night. These individuals were accused of being part of a rebel movement that Montesinos and the Fujimori administration were determined to crush. The farmers were executed without trial, and their bodies were left as a grim testament to the lengths to which Montesinos was willing to go to maintain control.

Montesinos’s Guilt: A Grim Admission

This week, Montesinos pleaded guilty to charges of homicide, murder, and forced disappearance, acknowledging his role in the killings. His admission of guilt, while bringing some measure of closure to the victims’ families, also serves as a reminder of the systemic abuse of power that characterized Fujimori’s presidency.

Fujimori himself, now aged 85 and recently released from prison following a controversial presidential pardon, faces charges related to the Pativilca massacre. Unlike Montesinos, Fujimori has not pleaded guilty, and his trial is eagerly anticipated by those seeking justice for the crimes committed during his tenure.

Montesinos has been behind bars since 2001, convicted on various counts of corruption and human rights abuses. The prison that now holds him, situated by the Pacific Ocean, is a product of his design—a bitter irony for a man who once epitomized the untouchable echelon of Peruvian politics.

Montesinos’s Dark Legacy: Corruption, Espionage, and Violence

The legacy of Montesinos’s tenure is a litany of corruption, espionage, and violence. His manipulation of the political landscape extended to paying bribes to members of Congress, business people, and media moguls, all captured on clandestine tapes that eventually precipitated the downfall of Fujimori’s government. These recordings, which surfaced in the early 2000s, revealed the depth of the corruption and the extent to which Montesinos would go to secure Fujimori’s grip on power.

The repercussions of Montesinos’s actions continue to reverberate through Peruvian society. The Pativilca massacre is but one instance of the systemic campaign of terror that sought to silence opposition and consolidate power by any means necessary. The Fujimori presidency once hailed for its economic reforms and efforts to quell insurgencies, is now inextricably linked to a legacy of human rights abuses and authoritarian rule.

The sentencing of Montesinos for the Pativilca massacre, while a significant milestone, is only a partial redress for the victims and their families. For many, justice remains elusive as the architects of Peru’s era of violence continue to evade full accountability for their actions. The case against Fujimori and the potential for his conviction represents a crucial test for Peru’s judicial system and its commitment to upholding the rule of law.

As Peru grapples with the shadows of its past, the story of Vladimiro Montesinos serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked power and the corrosion of democratic institutions. The path to reconciliation and healing is fraught with challenges. Still, only through confronting these dark chapters head-on can Peru hope to forge a future defined by justice, transparency, and respect for human rights.

Remembering the Victims: Six Farmers and the Cost of Political Machinations

In reflecting on the saga of Montesinos and the Pativilca massacre, it is imperative to remember the victims—six farmers whose only crime was being suspected of opposition to an oppressive regime. Their deaths are a stark reminder of the human cost of political machinations and the importance of safeguarding democratic values against the encroachment of tyranny.

The sentencing of Vladimiro Montesinos is not the end of this story but a continuation of Peru’s struggle to come to terms with its history. It is a moment for the nation to reflect on the lessons of the past and to renew its commitment to ensuring that such abuses never occur again. As Peru moves forward, it carries the weight of its history and the hope of a future where justice and human dignity prevail.

Also read: Mexico’s President Refutes Allegations of Cartel Funding in 2006 Campaign

In the end, the legacy of the Pativilca massacre and the broader reign of terror under Fujimori and Montesinos is a sad testament to the fragility of democracy and the enduring fight for human rights. While a step towards justice, the sentencing of Montesinos is also a call to action—a reminder of the vigilance required to protect the hard-won freedoms that are the foundation of any democratic society.