Argentina’s Napalpí Massacre and the Struggle for Indigenous Reparations

A century after the Napalpí massacre, which saw 500 Indigenous people killed by the Argentine State, descendants and activists are seeking justice and reparations.

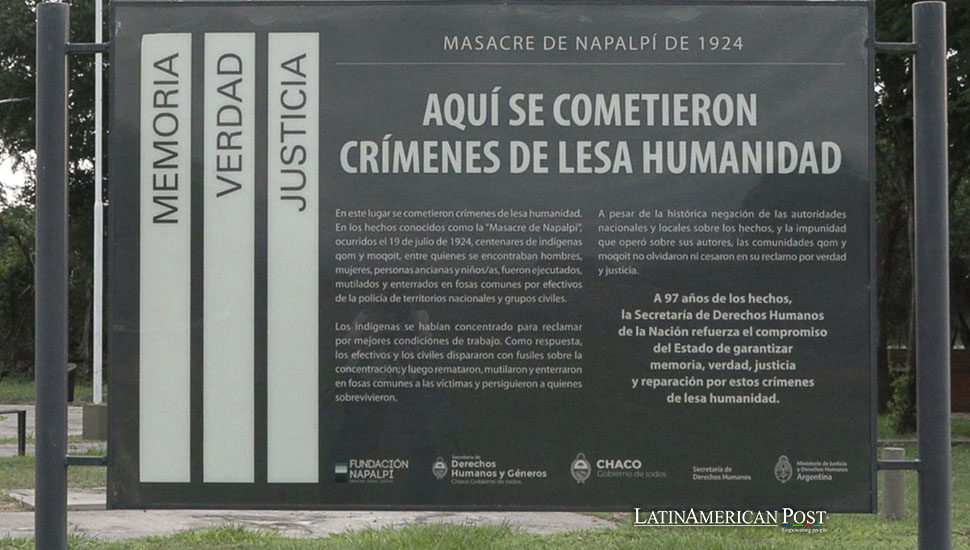

On May 19, 2022, nearly 98 years after the Napalpí Massacre, a historic verdict was delivered by Federal Judge Zunilda Niremperger. Reading her judgment simultaneously in the Qom and Moqoit languages, she declared the massacre a crime against humanity, organized by the Argentine state to exterminate the Qom and Moqoit Indigenous communities. “The state attacked the communities in a previously organized plan,” she affirmed, marking the first official recognition of the brutal events of July 19, 1924.

The massacre was part of a broader systemic effort to eliminate Indigenous communities during the formation of modern Argentina. Until recently, the state had neither investigated nor acknowledged these atrocities. The Napalpí was one of four Indigenous “reductions”—essentially concentration camps—established to control Indigenous populations. These lands, much like those created by the Spanish during the Cuban War of Independence, were designed to diminish and exploit their inhabitants.

Napalpí’s Indigenous residents were forced to work in cotton fields under oppressive conditions. Governor Fernando Centeno of the Chaco Region imposed strict controls, forbidding inhabitants from using their earnings outside the reduction and forcing them to pay for the transportation of their harvests and their work clothes. When the community protested for fair wages and better conditions, the government responded with violence, leading to the massacre that killed approximately 500 Moqoit and Qom people.

Reconstructing the Past: A Painful Process

Reconstructing the events of the Napalpí Massacre was a challenging task. The survivors’ testimonies went unheard for nearly a century, and no official investigation was conducted. However, the relentless efforts of descendants, historians, and sociologists supported by the current Chaco government led to the opening of a truth trial in April 2022. This trial aimed not to condemn the already deceased perpetrators but to validate the voices of the Napalpí communities and recognize the crimes committed against them.

Rosa Grilo, a survivor of the massacre, shared her harrowing account with Qom researcher Juan Chico. “I don’t know why they killed so many children and grown-ups. There was so much suffering,” she recalled. At over 100 years old, Rosa’s testimony was crucial in reconstructing the story. The massacre, which targeted primarily Qom and Moqoit communities in Colonia Aborigen, involved brutal tactics, including an airplane dropping candy to attract villagers before police started shooting, leading to days of violence.

The massacre must be understood in the context of the State Reduction for Indigenous People of Napalpí. Established by the Argentine State, these reductions operated between 1911 and 1956 in the Chaco and Formosa regions. Indigenous people were subjected to a debt system, charged for food, tools, and clothing, and forced to work in conditions akin to slavery. Sociologist Marcelo Musante explains that these reductions were part of a system designed to concentrate and discipline Indigenous communities, who faced threats of detention or death if they resisted.

The Fight for Justice and Recognition

The Napalpí Massacre left a deep scar on the Qom and Moqoit communities, resulting in the loss of language and culture and the displacement of many community members. In 2014, the Human Rights Unit of the Federal Prosecutor’s Office in Resistencia launched an investigation into the massacre, led by prosecutors Federico Carniel, Carlos Amad, Patricio Sabadini, and assistant prosecutor Diego Vigay. They uncovered extensive evidence that supported the claims of the massacre, leading to the truth trial in 2022.

Federal Judge Zunilda Niremperger’s ruling that the massacre constituted crimes against humanity as part of a genocide against Indigenous peoples was a significant milestone. Indigenous elder witnesses, including Melitona Enríquez, Rosa Chara, Rosa Grilo, and Pedro Balquinta, had to overcome their fear of the police to testify, with support from the local human rights secretariat. Their testimonies, along with historical evidence, helped establish the facts of the massacre and the coercive conditions faced by Indigenous people at the time.

The trial also aimed to provide reparations to the victims and their descendants. Analía Quiroga, president of the Napalpí Foundation, emphasized the importance of giving voice to the victims and proving the massacre through academic and legal means. This recognition restored some of the rights long denied to Indigenous communities.

The struggle for justice and recognition for the Napalpí Massacre continues. The verdict condemned the Argentine state-mandated reparative measures, including training federal forces on the events of the massacre and the genocide of Indigenous peoples. Gustavo Gómez, a member of the memorial working group, acknowledges the progress made but stresses that more needs to be done.

There has been significant participation in training sessions for federal forces, and the National Security Ministry has published a protocol for interacting with Indigenous populations from an intercultural perspective. The Education Ministry has also conducted training for teachers at all levels. Efforts are underway to convert the Napalpí historical site into a museum, and documents from the trial are being digitized for archival purposes.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and UN rapporteurs on the rights of Indigenous peoples have endorsed the trial as a model for adjudicating Indigenous massacres. However, pending issues include a formal apology from the national government and funding for the museum. There is also a proposal to rename Colonia Aborigen as “Napalpí,” pending local approval.

Embracing the Past to Forge the Future

The Napalpí Massacre and the ongoing efforts to seek justice and recognition are a testament to the resilience and strength of the Qom and Moqoit communities. The stories of survivors like Rosa Grilo, who passed away in April 2023 at the age of 115, continue to inspire new generations. Her granddaughter, Raquel Esquivel, now a member of the Napalpí Memorial team, emphasizes the importance of having Indigenous people tell their own stories. “It helps new generations continue our struggles and embrace our history and culture,” she says.

The fight for reparations and recognition is about addressing the past and ensuring a better future for Indigenous communities. The verdict and subsequent efforts to honor the victims of the Napalpí Massacre represent a crucial step toward healing and justice. However, the journey is far from over.

Also read: FIFA’s Zero Tolerance on Racism: Should Argentina Forfeit Copa America Title?

The legacy of the Napalpí Massacre serves as a reminder of the importance of acknowledging and learning from history. It underscores the need for continued solidarity and support for Indigenous communities in Argentina and across Latin America. By embracing their past and fighting for their rights, Indigenous peoples are paving the way for a more just and inclusive future.