China’s Backing of Latin America’s Rejection of Monroe Doctrine Explained

China’s support for Latin America’s rejection of the Monroe Doctrine signals a shift in global power dynamics. As the region asserts its independence, the long-standing U.S. dominance is increasingly at stake, reshaping the future of inter-American relations.

China has emerged as a significant player in Latin America economically and politically in recent years. In a striking move, China recently expressed firm support for Latin American countries in defending their sovereignty and opposing external interference, explicitly calling out the United States to abandon the Monroe Doctrine and its hegemonic policies. This declaration, made by Lin Jian, a spokesperson for China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, highlights the growing geopolitical shift in the region and raises questions about the continued relevance of the Monroe Doctrine. This 200-year-old U.S. policy has shaped the Western Hemisphere’s geopolitical landscape for centuries.

Initially intended to prevent European colonialism in the Americas, the Monroe Doctrine evolved to justify U.S. intervention and dominance in Latin America. For much of the 19th and 20th centuries, the doctrine was a cornerstone of U.S. foreign policy, allowing Washington to exert control over its southern neighbors. However, as China’s influence in the region grows and Latin American countries increasingly assert their independence, the doctrine’s relevance is being questioned. This feature explores the history of the Monroe Doctrine, the implications of China’s growing role in Latin America, and the potential future of U.S.-Latin American relations in a rapidly changing global order.

The Historical Grip of the Monroe Doctrine on Latin America

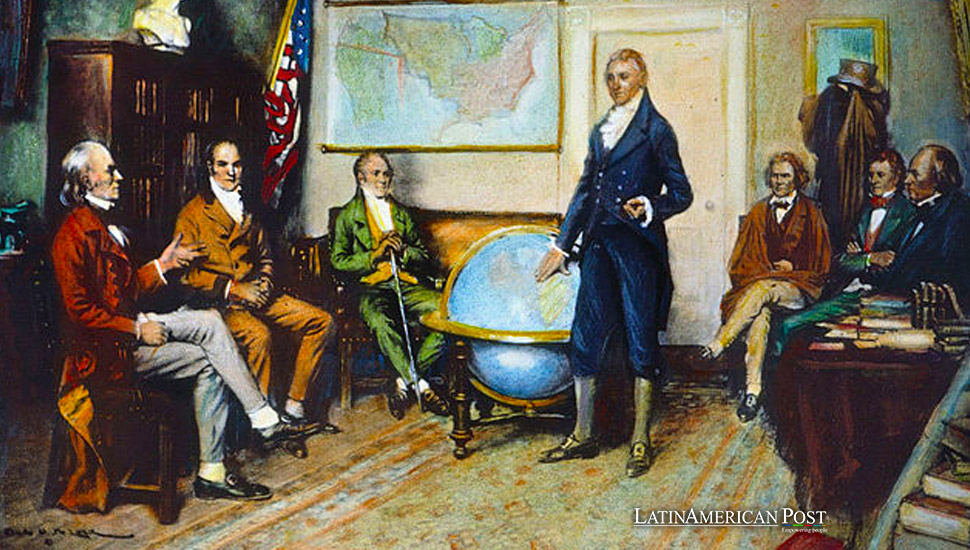

The Monroe Doctrine, articulated by President James Monroe in 1823, was initially conceived as a policy to prevent European powers from further colonizing the Americas. Monroe’s message to Congress declared that any attempt by European nations to interfere in the affairs of the Western Hemisphere would be considered a threat to U.S. security. The doctrine was anti-colonial at its core, asserting that the Americas were no longer open to European colonization.

However, the doctrine quickly became a tool for U.S. dominance over Latin America. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the U.S. had used the Monroe Doctrine to justify interventions in Latin American countries. One of the doctrine’s earliest and most significant applications was during the U.S. support for Mexican President Benito Juárez in 1865, which helped him defeat the French-installed Emperor Maximilian. This intervention underscored the United States’ willingness to use the doctrine to exert influence in the region.

Theodore Roosevelt expanded the doctrine further with his 1904 Roosevelt Corollary, which asserted the United States’ right to intervene in Latin American countries to stabilize the region. This policy led to numerous U.S. military interventions throughout the early 20th century, including in Santo Domingo, Nicaragua, and Haiti. These actions fueled resentment across Latin America, where many viewed the U.S. as a “great Colossus of the North,” exerting its power over weaker nations.

Over the decades, the Monroe Doctrine became synonymous with U.S. interventionism and paternalism in Latin America. While the doctrine was ostensibly designed to protect the region from European imperialism, it often resulted in the U.S. acting as an imperial power, dictating its southern neighbors’ political and economic directions. This historical context has left a lasting legacy of mistrust and skepticism towards U.S. policies in Latin America, particularly as the region increasingly looks to other global powers, like China, for partnership and support.

China’s Rising Influence

As the influence of the Monroe Doctrine wanes, China has stepped into the vacuum, offering Latin American countries an alternative to the U.S.-dominated order. Over the past two decades, China has rapidly expanded its presence in the region, becoming a major trading partner and investor. Chinese companies have invested heavily in infrastructure, energy, and mining projects across Latin America, providing much-needed capital and development assistance to countries long neglected by the United States.

China’s approach to Latin America is markedly different from that of the United States. Beijing’s foreign policy is guided by principles of non-interference and mutual respect for sovereignty, which resonate with many Latin American leaders who have grown weary of U.S. interventionism. This stance was clearly articulated by Lin Jian, who emphasized China’s support for Latin America’s “position of justice” in opposing foreign interference and safeguarding national sovereignty.

In recent years, several Latin American countries have deepened their ties with China, often at the expense of their relationships with the United States. For example, countries like Panama, the Dominican Republic, and El Salvador have switched diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to China, a move that has brought them closer to Beijing’s economic orbit. Trade between China and Latin America has also soared, with China becoming the largest trading partner for several countries in the region, including Brazil, Chile, and Peru.

China’s growing influence in Latin America has not gone unnoticed in Washington. U.S. officials have expressed concern over China’s expanding footprint, warning that Beijing’s investments could lead to economic dependency and political leverage. However, for many Latin American countries, China offers a welcome alternative to the United States, providing opportunities for development and growth without the strings attached to U.S. aid and investment.

The appeal of China’s model is particularly strong in a region that has long struggled with underdevelopment and inequality. For many Latin American leaders, China’s rise represents an opportunity to break free from the cycle of dependency and assert greater autonomy in their foreign and economic policies. This shift is emblematic of a broader realignment in global geopolitics, as emerging powers like China challenge the traditional dominance of the United States in regions like Latin America.

The Return of the Monroe Doctrine Rhetoric

In response to China’s growing influence in Latin America, there has been a renewed interest in the Monroe Doctrine within certain circles in the United States. While the doctrine had largely faded from U.S. foreign policy discourse in recent decades, it has seen a resurgence in recent years, particularly among those who view China’s rise as a threat to U.S. interests in the Western Hemisphere.

During the Trump administration, the Monroe Doctrine was explicitly invoked by officials like former National Security Advisor John Bolton, who declared in 2019 that “the Monroe Doctrine is alive and well.” This rhetoric was part of a broader strategy to counter China’s influence in Latin America, which the Trump administration viewed as a direct challenge to U.S. hegemony in the region.

However, the revival of the Monroe Doctrine has not been limited to the Trump administration. Even under President Joe Biden, elements of the doctrine’s logic have persisted, albeit in a more subtle form. U.S. officials have continued to express concerns about China’s involvement in Latin America, warning that Beijing’s economic engagements could undermine democracy and stability in the region. These warnings, often framed in terms of protecting Latin America from external influence, echo the paternalistic tone of the Monroe Doctrine.

Yet, as The Guardian has reported, this rhetoric is increasingly out of touch with the realities of Latin America today. Many Latin American leaders view U.S. warnings about China as condescending and hypocritical, given the history of U.S. intervention in the region. Countries like Mexico and Honduras have openly rejected U.S. criticisms, asserting their right to engage with China and other global powers on their own terms.

The revival of the Monroe Doctrine, whether explicit or implicit, risks alienating Latin American countries and driving them further into China’s orbit. As global power dynamics shift, the United States’ reliance on outdated policies like the Monroe Doctrine may do more harm than good, reinforcing the very trends it seeks to counter.

The Future of U.S.-Latin American Relations in a Multipolar World

The growing influence of China in Latin America and the resurgence of Monroe Doctrine rhetoric in the United States highlight the challenges of navigating a multipolar world. As Latin America increasingly asserts its independence on the global stage, the United States must adapt its approach to the region, moving beyond the paternalistic policies of the past.

One of the key challenges for U.S. policymakers is to recognize that Latin American countries are no longer willing to accept a subordinate role in the Western Hemisphere. The rise of China has given these countries greater leverage in their relations with the United States, allowing them to pursue more diversified and independent foreign policies. In this context, the Monroe Doctrine, with its emphasis on U.S. control over the region, is increasingly seen as anachronistic and counterproductive.

For the United States to maintain its influence in Latin America, it must move away from the interventionist mindset that has characterized its policies for much of the past two centuries. Instead, the U.S. should focus on building partnerships based on mutual respect, equality, and shared interests. This means engaging with Latin American countries as equals, rather than as junior partners in a U.S.-led order.

One potential avenue for improving U.S.-Latin American relations is through greater economic cooperation. While China has made significant inroads in the region, the United States remains a key trading partner and investor. By offering more competitive economic opportunities and addressing the region’s development needs, the U.S. can strengthen its ties with Latin American countries and counterbalance China’s influence.

Another important aspect of U.S. policy should be supporting Latin American efforts to address the root causes of instability, such as poverty, inequality, and corruption. Rather than viewing the region through the lens of great-power competition, the U.S. should work with Latin American governments to promote sustainable development and strengthen democratic institutions. This approach would not only improve the quality of life for millions of people across Latin America but also help stabilize the region, reducing the conditions that often lead to political upheaval and economic volatility. By prioritizing long-term, sustainable growth over short-term strategic gains, the United States could rebuild trust and foster deeper, more resilient partnerships.

In addition, the U.S. should consider adopting a more multilateral approach to its engagement with Latin America. This means working not only with individual countries but also through regional organizations such as the Organization of American States (OAS), the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), and other multilateral institutions that represent the interests of the region as a whole. By engaging with Latin America as a collective, rather than as a series of bilateral relationships, the U.S. could help to create a more integrated and cooperative Western Hemisphere.

It is also crucial for the U.S. to acknowledge and respect the growing autonomy of Latin American countries. The region’s leaders have made it clear that they no longer wish to be seen as mere extensions of U.S. influence, and any attempts to reassert dominance are likely to backfire. Instead, the U.S. should seek to engage with Latin America on a basis of mutual respect and shared values, recognizing the region’s right to pursue its own path in the global arena.

This shift in strategy could involve the U.S. stepping back from its traditional role as the regional “policeman” and instead acting as a partner in addressing shared challenges, such as climate change, migration, and public health. These issues, which transcend national borders and require collective action, offer opportunities for the U.S. to work collaboratively with Latin American nations in a way that builds trust and fosters goodwill.

Anticipating a new great power

As the global balance of power continues to evolve, the United States must adapt its approach to Latin America if it hopes to maintain its influence in the region. The days of the Monroe Doctrine and unilateral intervention are over. In their place, a new era of partnership and cooperation must emerge—one in which Latin American countries are treated as equals and respected for their sovereignty.

China’s growing role in the region is a clear signal that the old paradigms are shifting. Latin America is no longer willing to accept a subordinate position in the global order, and the U.S. must recognize this new reality. By embracing a more inclusive and respectful approach, the U.S. can help to shape a future in which the Western Hemisphere is defined not by domination, but by collaboration.

The future of U.S.-Latin American relations will depend on the ability of both sides to navigate this complex and changing landscape. For the United States, this means letting go of the vestiges of the Monroe Doctrine and embracing a more modern, cooperative approach to its southern neighbors. For Latin America, it means asserting its place on the world stage and building relationships with a variety of global partners—including, but not limited to, the United States.

In this multipolar world, where power is increasingly distributed among various global actors, the U.S. has an opportunity to redefine its role in Latin America. By prioritizing economic collaboration, supporting democratic institutions, and respecting the sovereignty of its neighbors, the United States can continue to play a significant role in the region—one that is welcomed rather than resisted.

The stakes are high, and the choices made now will shape the future of inter-American relations for decades to come. As Latin America looks to the future, the question remains: will the United States rise to the challenge, or will it cling to outdated notions of dominance that no longer serve the region—or the world?

Also read: U.S. Agents Battle Hidden Drug Mexico-China Networks

The shifting dynamics in Latin America, underscored by China’s growing influence and the region’s rejection of the Monroe Doctrine’s legacy, present both challenges and opportunities for the United States. By adapting its approach to one of partnership rather than dominance, the U.S. can maintain its relevance in Latin America, fostering a hemisphere characterized by mutual respect and shared progress. The choice is clear: embrace change and cooperation or risk being left behind in a world that is rapidly moving beyond the old paradigms of power.