Uruguay Revisits Its Dictatorship Era, Painting Faded Faces Anew

Uruguay’s memory of its last military dictatorship reverberates through a striking new exhibition that restores color to the black-and-white faces of the disappeared, reminding younger generations of the individuals behind each photograph—and honoring lives stolen under oppressive rule.

Color Where the Silence Used to Be

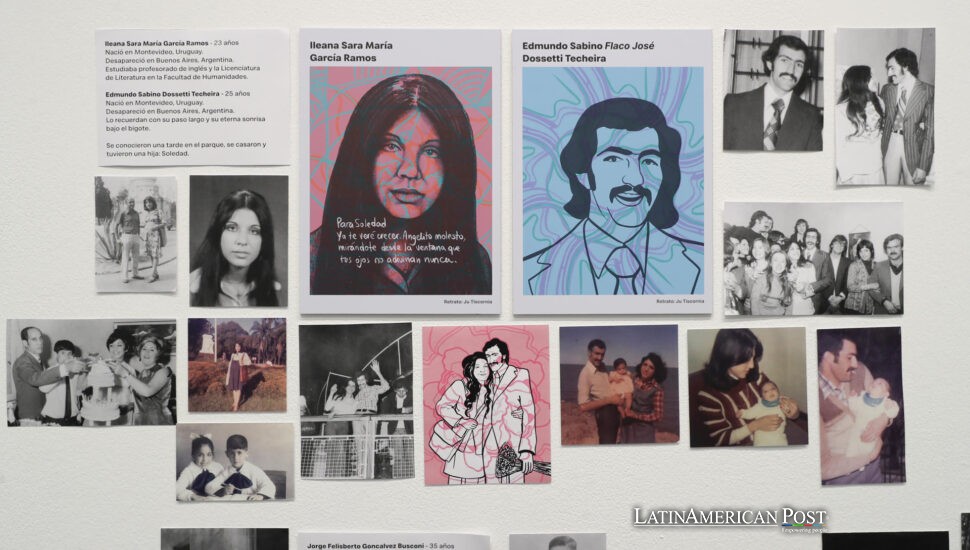

Every May 20, Montevideo falls quiet. Thousands advance through the streets clutching black-and-white photographs of the 197 Uruguayans who vanished under the 1973-85 dictatorship. La Marcha del Silencio’s ritual has long fixed those faces in time, drained of color and suspended in grief.

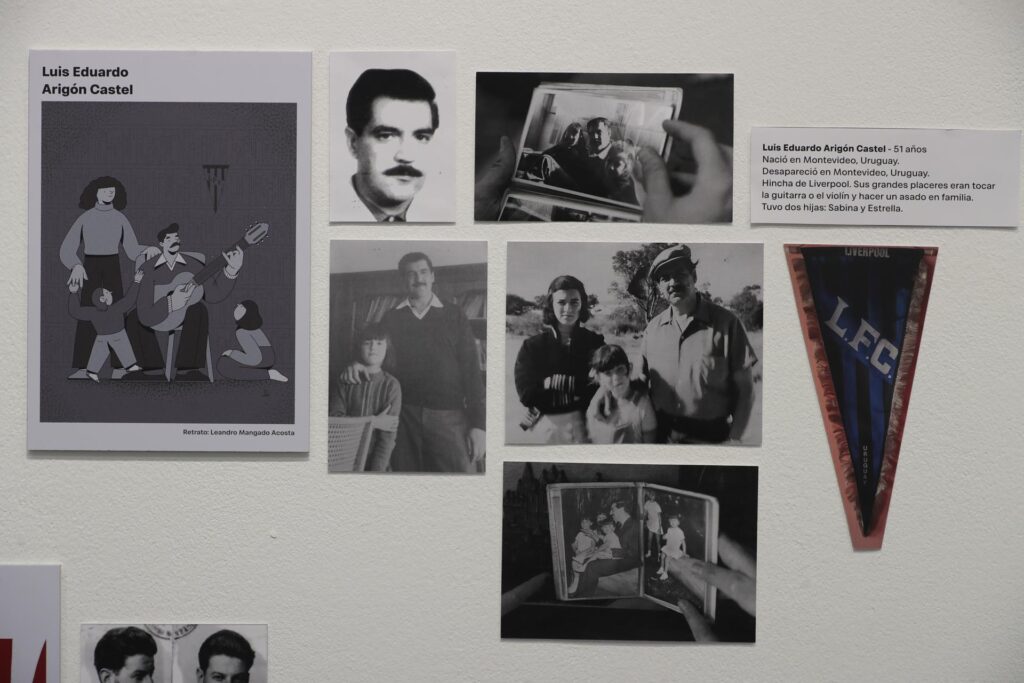

Step into the Subte Exhibition Center this season, and the shock is immediate: the same faces glow with reds, greens, café browns, and the blue of a summer sky. El color de la memoria pulls the missing out of monochrome and back into ordinary life—Saturday football, mates shared on a rambunctious porch, guitars slung over shoulders at beach bonfires. It feels less like a gallery than a family album interrupted mid-page.

Designer Kiara Lucas was eight when she learned two of the vanished—Mariana and Álvaro—were her aunt and uncle. The family knew little beyond the date they were taken. “I grew tired of the blank spaces,” she says. “I wanted to know their favorite songs, who they teased at school, whether they were dog people.”

Her curiosity grew into 197 Historias Ilustradas, a crowd-sourced archive of memories. Relatives, friends, and aging activists sent her scraps: a scribbled love note, a tram ticket, and lyrics from a Serrat song. Artists turned those details into portrait collages—ink, thread, pastel, and digital paint—anchored by Lucas’s insistence on full color. The Subte show enlarges that creative storm and lets the public wander through it.

Why Color Matters

Teenagers wander the rows, leaning in. Many confess black-and-white feels distant, like a schoolbook chapter. Curator Agustina Rodríguez nods: “Color tricks the brain into thinking now. Wrinkles sharpen, freckles pop, and clothing hints at a year or a mood. You meet a person, not a symbol.”

One portrait shows a young teacher tilting her head toward the camera, a cardigan the shade of mint ice cream. Next to it, a note from her sister: She never finished the crime novel on her nightstand. I kept it and still haven’t turned the last page. With color, the half-read book seems within reach.

Uruguay turns forty this year as a democracy. Plenty of citizens born since the return of civilian rule feel they “missed” the dictatorship. The exhibition argues otherwise. Most of the painters, illustrators, and embroiderers are under forty themselves. Some weren’t alive when the regime collapsed, yet they chose to stitch pockets, paint soccer cleats, and invent the sound of laughter held inside a still image. “That,” Lucas says, “is proof the urge to remember is generational, not nostalgic.”

Dynamic Memory

Beyond Uruguay’s borders, revisionist whispers grow louder—claims that the numbers were smaller, the crimes exaggerated, the disappearances inevitable side-effects of chaos. In that climate, filling in each life with color plays like defiance. “Deny a statistic, maybe,” Lucas shrugs. “Deny a grin that big? Harder.”

The show’s route ends with a long wall of tiny frames—197 in one line. Visitors pause, point, and whisper. A grandfather teaches his grandson to roll pastry for mosquitos. A medical student proudly wears her first stethoscope. Two men laugh so hard they lean on each other, cheeks flushed.

Seeing these moments intact makes the silence that followed unbearable. Yet it also underlines what persists: music remembered, recipes followed, a laugh inherited by a daughter who never met her father. The dictatorship stole bodies, not legacies.

Leaving With More Questions

By the exit, a guest book lies open. Entries range from schoolchildren’s neat block letters to an octogenarian’s trembling script. “I recognized my neighbor in frame 42. I never knew the story,” writes one visitor. Another simply murmurs, “Gracias por el color.”

Also Read: Ecuadorian Gangs Join Colombian Rebels to Expand Illicit Control

Investigations into the disappearances still grind on; some families hope for bones, others for confessions. The exhibition can’t supply either. What it offers is presence—vivid, every day, stubbornly alive. Step outside afterward, and the city’s billboards and traffic lights seem strangely brighter as if refusing to lapse back into gray.

Forty years into democracy, Uruguay keeps turning the page but refuses to close the book.

(Credit: EFE for quotes and interviews)