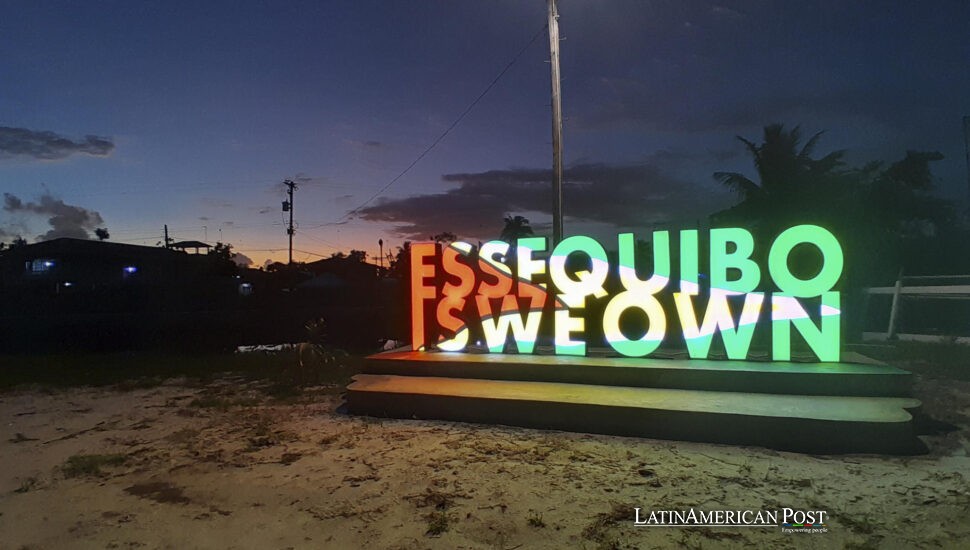

Venezuela Vote Fuels Unity and Resolve Across Guyana’s Disputed Frontier

Fear and patriotism mingle along the remote border communities of Guyana’s Esequibo region. As Venezuelan leaders press ahead with elections to appoint a “governor” in this contested territory, residents brace for the unknown, demanding respect for international rulings and territorial sovereignty.

Border Villages Brace as Tension Mounts

At dawn, the mist over Arau, a tiny settlement deep in Guyana’s forested Region 7, usually breaks to reveal children chasing chickens and traders loading riverboats bound for Venezuela. Lately, the air feels heavier. Shop shelves sit half-empty, and families huddle over transistor radios for news of Caracas’ plan to stage local elections on what Guyanese maps show as their side of the line.

“It has created real concern,” explains toshao Manuel Charlie, the village chief, speaking to EFE from a hammock strung beneath his stilt house. Fewer freight canoes now dock at Arau’s landing, he says, because Venezuelan soldiers have tightened checkpoints upriver. The settlement’s 290 residents rely on that trickle of rice, cooking oil, and gasoline; a week’s disruption leaves cupboards bare. “We are peaceful people,” Charlie adds, “but we need stability in the place we call home.”

Fifty kilometers away in Warapoka, a larger Indigenous community of around 600, the anxiety is identical—and more audible. Church bells rang last Sunday for a prayer service “to keep Esequibo safe,” then parishioners marched to the football field clutching Guyanese flags. Kevon Jeffrey, a village council member, says elders still remember the December 2023 Venezuelan referendum that claimed the region. “Some families spoke of leaving back then,” he tells EFE. “Now those fears are back.”

Across the savannas, homes and health posts flutter in green, yellow, and red—the national colors—sending a message to any curious drone camera. At night, WhatsApp groups ping with rumors: sightings of armored patrols, whispers of conscription across the Cuyuni River. Most prove exaggerated, yet each one tightens the knot in villagers’ stomachs. They are proud of the land their grandparents cleared, but they also know gunfire travels faster than official bulletins.

Guyana’s Leaders Draw a Line

The quarrel itself is older than every living resident. In 1899, an international tribunal fixed Guyana’s western border along the Essequibo River. Venezuela has disputed that ruling, calling the award a colonial swindle. Georgetown says the case is closed; Caracas insists the map needs redrawing. The disagreement simmered for decades—until oil fields off Guyana’s coast turned the mud banks into prime real estate.

President Nicolás Maduro’s latest move to install a “governor” in Esequibo, ignoring a stern warning from the International Court of Justice, crossed a line for Guyana. “We will not stand idly by,” President Irfaan Ali declared in a televised address, urging Venezuela to respect “international rights.” Defense chief Brigadier Omar Khan followed up with a blunt request to dozens of visiting toshaos: report any strange activity immediately. “Guyana’s sovereignty isn’t up for negotiation,” he said, prompting a ripple of nods across the conference floor.

Government planners choreograph a twin response—muscular but measured. On 26 May, the anniversary of independence from Britain, they will raise the flag in Anna Regina, the capital of Essequibo’s Pomeroon-Supenaam region, complete with school choirs and a military salute. The location is no accident; it plants the celebration squarely inside the contested zone. Diplomats in Georgetown also work phones from Brasília to Washington, seeking statements that any ballot boxes planted by Caracas would violate the ICJ’s provisional measures.

Privately, officials acknowledge limited capacity for a prolonged standoff. Guyana’s army counts a few thousand troops; Venezuela’s numbers dwarf that. Yet confidence flows from two sources: a binding court process in The Hague and a swelling sense of national unity. Opposition parties, usually quick to skewer the administration, issued a rare joint communiqué backing Ali’s stance. “Regarding Esequibo, we are one house,” opposition leader Aubrey Norton said on the parliamentary steps.

Maduro, undeterred, vows to “fully recover” what he calls Guayana Esequiba—words that crackle across shortwave radios in border hamlets. Many Guyanese read the rhetoric as a theatre for Venezuelan voters ahead of Caracas’ presidential race. Even so, every speech fuels another round of contingency meetings in Georgetown and another night of lost sleep in Arau.

Lives in Limbo Amid a Historic Feud

Politics aside, each escalation lands hardest on those who straddle the invisible border for survival. Goods once floated effortlessly between Esequibo and the Venezuelan town of San Martín de Turumbang. Now, traders face new fees and sudden closures of makeshift checkpoints. Maria Thomas, who sells cassava bread in Arau, used to cross twice a week for kerosene and spices. “If the soldiers say no, my stove stays cold,” she sighs, folding her arms outside her thatched kitchen.

Teachers worry, too. Warapoka’s school had planned a cultural exchange with a sister community across the frontier—language lessons, shared dances—but the visit is on hold. “How do I tell eleven-year-olds the other side might no longer welcome them?” asks headmaster Joseph Stanley. Telephone reception fades after sunset, and parents try to reassure children with stories of Amerindian resilience. Still, talk of an impending “governor” from Caracas conjures images of checkpoints on forest trails that have been footpaths for generations.

The ICJ’s directive that Venezuela suspend any administrative acts in the territory offers legal comfort but zero day-to-day certainty. Farmers still need diesel; pregnant women still need clinics. Formal or de facto blockade could turn remote hardships into full-blown crises. “We depend on each other across that river,” Jeffrey reminds outsiders. “Cut the lifeline, and we all lose.”

Yet defiance runs deep. Arau’s village council convened last week under the giant kokerite palm at the clearing’s edge. After prayer and debate, members voted to stay put whatever comes. They drafted a statement—handwritten, signed in ink and thumbprint—asserting “unalterable loyalty to the Cooperative Republic of Guyana.” The paper will travel 250 kilometers by boat, truck, and bus to reach the capital, where it will join dozens of similar pledges now piling up on ministry desks.

Whether diplomacy or bravado decides the next chapter remains to be seen. Georgetown hopes its legal case and oil-rich partners will temper Venezuelan ambitions. Caracas, fighting inflation and an election of its own, may decide symbolism suffices. In the meantime, the people of Esequibo live in a contradiction: remote villages suddenly thrust into the center of continental politics, armed only with flags, cell phone cameras, and an unwavering sense of place.

Also Read: Uruguay Revisits Its Dictatorship Era, Painting Faded Faces Anew

“We pray for peace,” Toshao Charlie says, his voice crackling over the line as evening frogs begin their chorus behind him, “but if they force us, we will defend our land—because it is ours and always has been.”