Who Killed Gaitán? Conspiracies Behind the Assassination That Changed Colombia

The assassination of Jorge Eliécer Gaitán happened on April 9, 1948. It destroyed Colombia’s hopes for social reform plus began the Bogotazo riot, which destroyed the city. Though many investigations occurred, and official rulings took place, his death continues as a labyrinth of questions. Because of this suspicion and social repercussions, the case has stayed alive for decades in Colombian historical memory.

The Charismatic Rise of a Political Giant

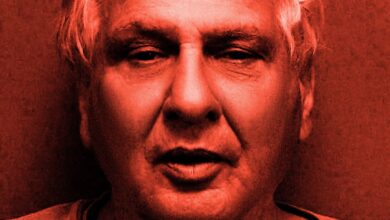

In the mid-twentieth century, few figures in Latin America could match the extraordinary magnetism of Jorge Eliécer Gaitán. He was born into a humble family in Bogotá. He climbed through the levels of the Colombian Liberal Party. He gained support from intellectuals and poor people. His speeches made common people hopeful, in addition to people who felt the nation’s politics did not deal with poverty and unfairness. The powerful speeches featured daring ideas. He challenged institutional power and scorned the oligarchy’s neglect of the “national country,” a term he used to describe most Colombians who felt marginalized by a self-absorbed political class.

His swift ascent seemed unstoppable by the late 1940s. He had served as Mayor of Bogotá, Minister of Education, and Minister of Labor. Following a brief departure from the Liberal Party during the early 1930s when he headed his populist group, he returned and was now the clear favorite in Colombia’s 1950 presidential race. For his followers, Gaitán represented the hoped-for advocate of fair economics and land change, someone willing to fight established powers. To his critics, he was a threat of unpredictable scope, a man capable of galvanizing popular fury against decades of Conservative-Liberal rule that had done little to improve the lives of the working poor. Some whispered that even the moderate wing of his own Liberal Party recoiled at the explosive possibility of a Gaitán presidency.

Behind his thunderous populist slogans and rhetorical calls to uplift the masses, Gaitán possessed a restless energy. He was not just campaigning to win elections but to transform what he labeled the “political country” into a more inclusive system where landlords and traditional power brokers could no longer ignore the clamor for rights and resources. He had faced setbacks before, most notably in 1946 when a split among Liberals allowed a Conservative, Mariano Ospina Pérez, to seize the presidency. Yet by 1948, his star burned brighter than ever. He rallied one hundred thousand followers in a massive March of Silence to protest mounting violence against Liberals in the countryside. He recruited a fervent base that saw him not merely as a standard-bearer but as a redeemer who would rewrite the country’s destiny.

A Shocking Day In Bogotá

By early April of 1948, international dignitaries had gathered in Bogotá for the Ninth International Conference of American States, an event poised to create the Organization of American States and fortify an anti-communist bloc in the hemisphere. Gaitán himself had pressed for the voice of ordinary Colombians to be heard amid the bustle of formal dinners and polished diplomatic sessions. Some accounts suggest he intended to meet with young student activists planning protests, including an ambitious Cuban named Fidel Castro.

On April 9, Gaitán and several associates emerged from his law office on Bogotá’s bustling Carrera Séptima. They planned to stroll the short distance to lunch. It was early afternoon, the city brimming with daytime crowds and diplomats, and everyone was excited about the significant Pan-American meeting in progress. Then, in a single, jarring moment, a volley of gunshots shattered the midday routine. Startled witnesses saw Gaitán collapse with wounds in his back or chest, possibly three shots fired in quick succession. Anxiety showed briefly on the other side of the street – then chaos broke out. People hurried to assist him and put him on a rough stretcher. But their desperate attempts to get him to the nearby Clínica Central failed. The leader, famous for giving millions hope, passed away shortly after.

As news of his murder spread, the unthinkable happened. Bogotá erupted in violence plus disorder, a sudden explosion from a place of quiet. Angry crowds attacked government buildings, churches, and police stations next to private businesses. Thousands of protesters filled the streets because they wanted revenge plus an outlet for their pent-up anger. Church doors were forced open as some turned wrath on the clerical authorities they associated with the Conservative leadership. The city’s center blazed with flames and billowing smoke for nearly ten hours, a cataclysm that would earn the name Bogotazo. Damage estimates rose along with the death toll, which some historians place in the thousands. The commotion spread past the capital and riots began in other cities. It also worsened harsh partisan disputes in the rural areas.

Because of the murder, people instantly blamed Juan Roa Sierra. He did not encounter a trial or any questioning. A violent group pulled him from a pharmacy, where he sought safety, and they beat him to death there. It was an act of swift, savage retribution that erased the possibility of further testimony from the only known suspect. In the minds of many Colombians, Roa died too conveniently, silencing the question of who truly planned the assassination. The official record eventually declared him a lone gunman. Yet hardly anyone found that conclusion satisfying, least of all a public reeling from the violent shockwaves that rippled through society for years to come.

The Alleged Gunman and The Mysterious Flaco Con Ojos De Loco

Roa Sierra’s motivations have been scrutinized from every angle, though certainty remains elusive. Some accounts describe him as unemployed and desperate, his mental stability eroded by illusions of grandeur. Others highlight strange connections to mysticism, rumors of him believing he was the reincarnation of figures like Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, the founder of Bogotá. The notion that a mentally unbalanced man could singlehandedly eliminate Colombia’s most prominent populist leader with an accurate flurry of gunfire on a packed boulevard constantly strained the credibility of those who believed powerful forces must have pulled the strings.

In the aftermath, journalists and investigators searched the capital for additional leads. A famous report from Time Magazine featured a detail that still haunts many historical accounts: rumors of a “flaco con ojos de loco,” a thin man with crazy eyes who was allegedly seen talking with Roa just before the shots rang out. Some witnesses insisted that this shadowy figure posed as Juan Roa, entering Gaitán’s office in the days before the murder and inquiring about a meeting. The police apprehended one suspect, a printing plant mechanic at the Conservative newspaper El Siglo, but no definitive tie to the assassination was ever proved. The story of the flaco con ojos de loco only stoked the idea that unseen conspirators had orchestrated everything, allowing Roa to be identified—correctly or not—as the fall guy.

There were other inconsistencies. Some who rushed to the scene swore the man they saw pinned against the drugstore gate did not match Roa’s appearance. Others pointed out that even if he had purchased a revolver just days before, he might have lacked the skill to pull off a lethal ambush. Almost every statement or rumor sparked new speculation, prompting investigators to scour hotel ledgers and private records for evidence of foreign agents or wealthy sponsors behind the crime.

Although a later Colombian judicial decree declared Roa Sierra solely responsible, many found that official story too neat, especially given the political tensions swirling around Gaitán. Was it plausible that a single man of limited means, likely struggling with mental disturbances, had murdered one of the hemisphere’s most promising populist leaders at the most explosive possible moment, then triggered a national uprising that forever altered Colombia’s trajectory? Doubt settled like a heavy fog, refusing to dissipate.

The Conspiracy Theories That Refuse to Die

Public suspicion drew immediate parallels between Gaitán’s murder and the assassination of John F. Kennedy in Dallas fifteen years later. Both men stood at the apex of their political realms, fueling hope or hostility among powerful elites. Both were killed on a crowded city street in broad daylight by alleged lone gunmen with questionable backstories. Both official inquiries insisted on solitary guilt. Both saw their accused killers cut down before standing trial. And both left behind a swirling mass of theories pointing to government conspiracies, foreign meddling, or manipulations by intelligence agencies.

In the case of Gaitán, countless fingers have pointed in different directions. One theory alleges that the ruling Conservative government, threatened by the unstoppable tide of Gaitanismo, authorized the elimination of a radical opponent who could smash the existing order.

Another theory suggests that anti-Gaitanista factions within the Liberal Party felt threatened by his meteoric rise. They decided that preventing his presidency was the only way to preserve their aristocratic privileges.

Skeptics also emphasize the timing: the Ninth International Conference of American States was underway, culminating in the formation of the Organization of American States, a prime venue for the United States to project its influence and champion an anti-communist agenda. Gaitán was known for his outspoken stance against foreign corporate exploitation, particularly regarding companies like the United Fruit Company, which had been implicated in earlier labor massacres. Some wonder if Washington or allied interests feared he would nationalize industries or disrupt profitable arrangements, prompting a secret plan to remove him.

Quickly after the event, Conservative leaders and the US group suggested possible communist involvement. These people argued that Soviet supporters or nearby communist groups planned the killing. They wanted to wreck the meeting, and they looked to they were beginning revolutionary trouble. The presence of a young Fidel Castro in Bogotá that week only fueled these whispers, though no credible evidence ever emerged linking him to the crime. Nearly every facet of Gaitán’s assassination has been spun into a labyrinth of contradictory leads, government denials, alleged cover-ups, missing documents, and suspiciously timed scapegoats.

For many Colombians, the official account that Roa Sierra acted alone and out of personal grievance never accounted for the massive stakes. Gaitán was poised to alter national power structures more profoundly than any politician before him. To some, it seemed inevitable that shadowy actors —domestic or foreign— would conspire to ensure that never happened.

Historians note that high-ranking figures, including possible conspirators from within Gaitán’s circle, were never seriously interrogated once the city exploded in riots. The initial investigations proved chaotic, and any subsequent efforts at a sober inquiry were overshadowed by the nationwide violence known as La Violencia, in which party-affiliated armed groups ravaged the countryside for the next decade, leaving at least two hundred thousand dead.

The Legacy of a Man Who Would Not Be Silenced

Few assassinations have so thoroughly upended a nation’s course. Gaitán’s murder remains a searing historical pivot point that ignited the Bogotazo, burned much of downtown Bogotá to embers, and unleashed a torrent of partisan warfare that decimated entire rural communities. Colombia would struggle for decades to mend the fractures wrought in those days of rage. To many observers, Gaitán’s potential presidency represented a fork in the road, a chance at sweeping reform that might have preempted the worst extremes of violence that consumed the country through the mid-twentieth century.

His legend endures among generations who see him as a symbol of hope, the orator who raised his voice for the dispossessed. Many people think that Colombia’s political path would have changed if Gaitán stayed alive. It might have avoided the periods of guerrilla actions, the problems with drugs, and the cruel actions of paramilitaries that later controlled the nation. Because this opinion is either a hopeful dream or a genuine respect, it holds considerable weight in society. April 9 is commemorated as the National Day of Memory and Solidarity with Victims of Armed Conflict. The memory of Gaitán hovers over these commemorations, both as a tragic figure and a revered icon for those who insist that social justice can and must be realized in Colombia.

Yet that memory also remains haunted by profound uncertainty. With the lynching of Juan Roa Sierra, the question of culpability for Gaitán’s murder was cast into a void where rumor and hypothesis swirl perpetually. Official rulings by Colombian courts have declared that only Roa is to blame, but these findings have never silenced the whispers that more powerful and cunning actors orchestrated the act or at least paved the way for it. Eyewitness diaries and testimonies, the mess of clashing assertions shortly after the shooting, alongside later censorship and legal mess, indicate a mystery. The official story fails to contain this mystery.

The parallels to the Kennedy assassination remain striking in their resonance. Both events became national trauma, steeped in a conspiracy that revealed more profound anxieties about government power, foreign influence, and the fragility of political dreams. Just as Americans debate what happened in Dallas, Colombians continue to parse every contradictory detail about April 9, 1948, unwilling to believe that fate alone, assisted by one desperate man, changed their destiny forever.

No matter which theory one chooses to believe—whether a lone, troubled gunman acted alone or if there was a complex web of international espionage, secret deals, and double agents—Gaitán’s assassination remains a pivotal moment in Latin American history. It signifies the tragic power of a single bullet to take not just one life but also to crush the hopes and aspirations of millions. After the conflict, the nation encountered intense violence, distrust, and horror. The effects of this disorder exist today, and people ask for accountability. People demand sealed archives open, and the sense that political tactics obscured the truth stays.

The enduring interest in Jorge Eliécer Gaitán demonstrates his link to ordinary Colombians and the rage that followed his death. Gaitán went past political divisions, for he spoke to a population that desired reform. Given his assassination, the national psyche experienced trauma. This may explain why, even after so many years, Gaitán’s death continues to resonate in the collective imagination of the country. Its shadow looms every time Colombia confronts political unrest, new leaders promise a better future but shy away from the radical reforms he once championed, and historians attempt to unravel the darkest secrets of that fateful day.

Also Read: Ecuador’s Largest Prison: Battling Gangs, Disease, and Despair

Latin America has seen its share of unsolved political crimes, but Colombia’s mystery surrounding Jorge Eliécer Gaitán stands out as a tragedy of continental proportions. The man who declared, “I am not a man; I am a people,” was silenced on a public street, yet his voice endured. The legends of conspiracies swirl, the official narrative remains unconvincing to many, and the specter of what might have been clings to each retelling of his story. It is, without question, one of the region’s greatest and most haunting enigmas, a jigsaw puzzle missing vital pieces that, if found, might finally reveal what truly happened on April 9, 1948, and why.