A Bold Vision May Spark El Salvador Mining Renaissance

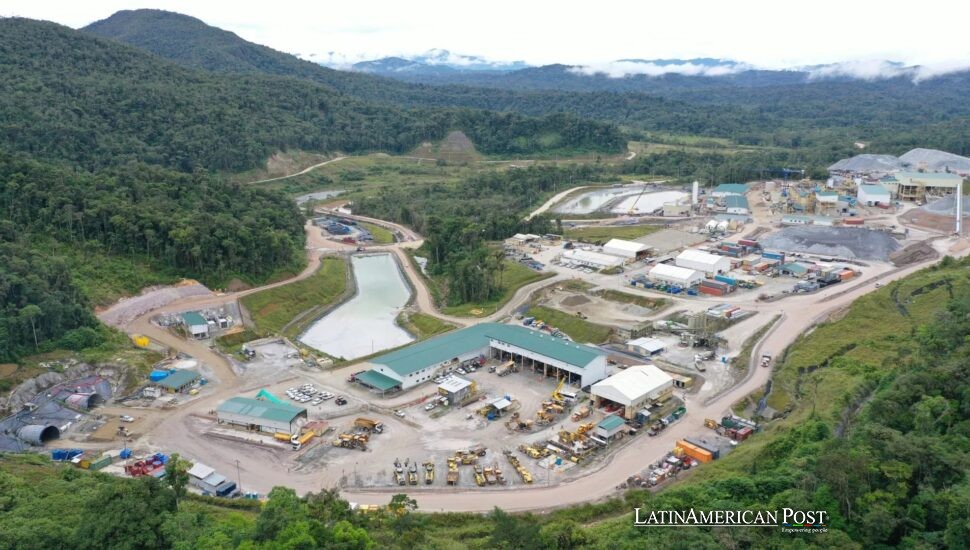

El Salvador’s choice is to change its economy by bringing back responsible mining under President Nayib Bukele’s new law. Though some doubt remains, supporters say that close supervision plus public involvement may create a long-term benefit.

From Outright Ban to Cautious Embrace

A few years back, the thought of letting metal mining happen in El Salvador appeared unimaginable. In 2017, this nation halted the activity entirely, citing possible damage to nearby communities, farmland, and valuable water sources. Environmentalists praised the ban—a daring move for a small yet densely populated country striving to guard its scarce natural resources.

Fast forward to late 2024, and the landscape has changed dramatically. President Nayib Bukele’s administration succeeded in passing a new General Metallic Mining Law, effectively reopening the country to mining—but with updated rules, heavier government oversight, and, at least in theory, a more sustainable outlook. The law ignited arguments on both sides: critics worry about going back to harming nature, while supporters notice a chance for new work, infrastructure, plus growth in often neglected areas.

Bukele himself claims this law differs significantly from old rules. Rather than permitting companies and hoping they respect nature’s rules, his government plans to take a direct share in any big mining project. This implies that the state becomes more than an observer ‒ it becomes a co-owner carrying duty and power. Critics and champions of the law concede it’s a radical change of approach: no longer is the government simply an observer. If the law unfolds as written, the administration will have a legal obligation to ensure stringent environmental standards, proper waste management, and equitable benefit-sharing with local communities.

At present, Bukele notes that no actual mining licenses have been granted yet. The government first wants to set up an office responsible for negotiating with potential investors from around the globe. Any mining company that wants to extract El Salvador’s minerals must be prepared to work hand-in-hand with government officials, who promise to watch operations, labor standards, and, most critically, environmental protections. In principle, this arrangement might provide unprecedented power for the Salvadoran state to enforce correct practices—but whether that translates into reality depends on execution, funding, and willingness to be transparent with the public.

Why Mining Matters for Economic Development

Advocates for mining return claim this industry might transform the Salvadoran economy. Many know the nation faces scarce natural resources, high migration, and few major investments. Though service and agricultural sectors sustain the economy, new revenue’s appeal is strong.

In theory, a responsible mining sector could bring thousands of well-paid jobs, upgrade transportation infrastructure, and provide a fresh injection of foreign capital. Communities near mining sites also benefit from direct partnerships with companies as they negotiate improvements such as paved roads, enhanced medical clinics, or educational programs. Proponents see it as a chance to uplift regions often left behind in the country’s development.

Moreover, there’s the broader global context: Many modern industries—from electric vehicle production to smartphone manufacturing—demand metals like copper, lithium, and rare earth elements. If El Salvador can position itself within these global supply chains, it can reap lucrative gains that could strengthen its currency and reduce dependency on external aid. The government could theoretically invest those funds in critical social programs by ensuring a percentage of profits goes back into Salvadoran hands.

However, none of these bright prospects are guaranteed. Successful partnerships require rigorous oversight to prevent corruption, labor exploitation, or environmental shortcuts. Historically, in regions around the world where governments have shared ownership in extractive industries, the effectiveness has hinged on the integrity of public institutions.

If oversight bodies are weak, politically compromised, or lacking expertise, any theoretical benefits can quickly evaporate.

Still, advocates maintain that El Salvador’s relatively tiny size might prove an asset. They argue it’s easier to enforce environmental and social regulations in a compact territory where problems can be quickly spotted and remedied, especially when compared to sprawling countries with remote mining sites. In a best-case scenario, the government could emerge as a sustainable mining model, showcasing how modern extraction methods—combined with political will—can generate wealth without leaving behind a wake of ecological ruin.

Addressing Fears Over Water and Pollution

Critics, meanwhile, stress the potential risk to El Salvador’s waterways—especially the Lempa River, the region’s most important water source, crucial for drinking water, agriculture, and hydroelectric power. Environmental groups have warned that large-scale mining near the river’s basin could lead to irreversible damage, contamination with heavy metals, and the displacement of rural communities that depend on subsistence farming.

President Bukele has publicly argued that the country’s rivers aren’t currently polluted by mining—given that industrial mining was banned in 2017—but by raw sewage and garbage disposal. He contends that if the country is serious about cleaning up its water resources, it should direct more energy towards upgrading waste management and wastewater treatment facilities. Indeed, many of El Salvador’s municipalities still lack modern sewage systems, allowing unfiltered waste to flow straight into streams and rivers.

To environmental advocates, the president’s argument may skirt around the potential long-term dangers of mining. Historical examples from various parts of Latin America show that even with “best practices,” accidents happen—like tailings dam failures or leaks of toxic chemicals—which can devastate entire ecosystems within days. The key question is how effectively El Salvador can regulate newly authorized mines to prevent those outcomes.

Advocates for the new law highlight that technology progresses significantly, offering safer methods to manage plus handle mining waste. They imagine modern water treatment systems and zero discharge tailings facilities ‒ no untreated water exits the mining area. On paper, these methods reduce the threat of toxic seepage into rivers; consistent monitoring and maintenance will be crucial. They also highlight that any company cutting corners with government ownership would theoretically face immediate pressure from its largest partner: the Salvadoran state.

Another salient factor is the social dimension of water use. When mining companies set up operations in many parts of the world, water consumption spikes to feed processing plants. Locals can sometimes feel squeezed out or experience shortages. Bukele promises that if the government holds a direct stake, local needs will be prioritized rather than overshadowed by profit motives. Realistically, ensuring that promise in law and practice requires a robust legal framework and real-time public reporting so communities remain well-informed of water allocation decisions.

Potential Roadmap for a Responsible Mining Future

Specialists and supporters suggest that mining laws in El Salvador might become real triumphs if the government and companies are more open during talks and agreements, giving people access to details on profit-sharing deals in addition to environmental duties.

Independent environmental impact studies by unbiased professionals should precede any new mining operations to examine tailings management, biodiversity, water quality, and potential effects on local communities. Neighboring towns would need to be closely involved in monitoring possible environmental or social violations, with the authority to report and address issues early.

The Salvadoran government should also assemble specialized teams of experts—engineers, environmental scientists, geologists, and economists—with adequate budgets and legal backing to enforce compliance. Strong dedication to fixing mining areas after work finishes is necessary. Using escrow or clean-up money before mining begins helps ensure land restoration.

Meanwhile, policymakers must recognize that improving the country’s overall pollution control systems—such as sewage treatment and proper waste disposal—is equally critical since mining alone is not the main or only factor affecting water quality. Addressing these broader problems together, El Salvador strives for a responsible path that promotes growth without harming its environment or the well-being of its people.

The gap between environmental activists and the pro-mining group seems nearly impossible to bridge. But there’s room for a middle path if both sides accept nuanced realities: the environment does need stronger protections, and the economy could benefit from carefully regulated extraction. That balance is delicate but not impossible.

Bukele’s administration repeatedly insists that no permits will be granted in haste.

During this changing time, leaders aim to improve the legal system by gathering ideas from scientists, legal experts, community leaders, and international observers with ethical mining experience. With proper action, El Salvador may break the old cycle of harmful mining in Latin America ‒ creating a thoughtful way that mixes economic growth with genuine care for water, land, and people.

Finding Common Ground and Looking Ahead

In numerous ways, El Salvador’s return to mining reflects more significant debates worldwide about taking resources. The desire for minerals has increased, pushed by renewable energy tech, electric cars, plus the digital economy. Opponents of mining worry about repeating the mistakes of the past: tailings spill, worker exploitation and corporate profits overshadowing community rights. However, proponents point out that no modern society can function without metals. The question, then, asks not if mining should happen but how to mine responsibly and who gains the benefits.

By co-owning operations, the government thinks it keeps control ‒ guiding away from careless shortcuts. This method brings risks, though. If the state lacks the expertise or political honesty to enforce strict rules, owning part of mining could make them ignore bad practices for profit’s sake. That’s why transparency and real-time oversight mechanisms from civil society become essential guardrails.

Supporters envision a future where the country’s once-forbidden mines become paragons of green technology, from cutting-edge water recycling systems to solar-powered equipment. They picture a pipeline of local engineers, geologists, and environmental scientists—trained with company funds—taking the reins of Salvadoran resource management for generations to come. They even see potential for cross-border collaboration with neighboring Guatemala and Honduras, focusing on the entire Lempa watershed in a unified effort to protect shared natural assets.

While the road ahead is bound to be bumpy, the opportunities are significant. If managed well, mining revenues can help modernize public infrastructure, fund healthcare, and strengthen environmental stewardship in areas that have historically been overlooked. A portion could go to building wastewater treatment plants that address the contamination concerns Bukele highlighted or to rehabilitating existing dumps that currently leak pollutants into rivers.

To skeptics, this might sound overly optimistic—after all, many countries have tried and failed to strike the right balance. However, proponents insist that El Salvador’s small size and engaged civil society provide a built-in advantage: everyone pays attention. News travels fast, watchdog groups can mobilize quickly, and the government cannot easily hide environmental disasters or hush up local discontent. The country’s compactness might make accountability more accessible than in larger nations where mining sites sit thousands of miles from government capitals.

Also Read: Bukele’s Policies Are Transforming El Salvador’s Security Crisis

Ultimately, whether this law signifies a responsible new era or a repeat of painful history will hinge on how deliberately El Salvador shapes its regulations and invests in strong, ethical oversight. Laws on paper are one thing; actions in the field are another. The government’s bold rhetoric about co-ownership and transparency will mean little if local communities are sidelined or water testing data is kept secret. But if President Bukele delivers on his pledge for a new kind of mining—anchored in fairness, technological innovation, and fundamental ecological safeguards—El Salvador could show the world that development and environmental care need not be mutually exclusive.