Brazil Becomes China’s New Power Bridge in Latin America

Across Brazil's ports, power grids, and city streets, China's presence has moved from background noise to daily reality. Factories, electric cars, food-delivery apps, and energy giants now anchor Beijing's influence inside Latin America's largest economy—reshaping regional power dynamics and shrinking the space Taiwan and Washington once relied on.

From soy and ore to cars, apps, and everyday life

Not long ago, China's role in Brazil could be summed up in bulk cargo: soybeans, iron ore, and oil. Ships left Santos and Paranaguá full; Chinese consumer brands barely registered in São Paulo malls or on Rio's roads. That era is over. China's economic footprint has woven itself into Brazil's industrial core and consumer habits, transforming the country into what The Diplomat calls Beijing's preferred gateway into Latin America.

BYD electric vehicles now swarm Brazilian streets, commanding more than 80% of domestic EV sales. Chinese-backed apps like 99, the ride-hailing platform run by Didi, and Keeta, Meituan's food-delivery challenger, fight for dominance in cities where Uber and iFood once operated with little worry. Chinese firms are no longer just exporters selling to Brazil. They are investors, employers, and trend-setters, shaping what Brazilians drive, how they order dinner, and where the country's energy comes from, according to The Diplomat.

This shift carries geopolitical weight. As Chinese capital sinks deeper roots into Brazil, Latin America's most populous nation is becoming a continental launchpad for Chinese technology and manufacturing—challenging Washington's historic dominance in the hemisphere and indirectly eroding the diplomatic oxygen Taiwan enjoys among its last allies, especially Paraguay.

A surge in investment—and Beijing's growing leverage

In raw numbers, the United States still edges out China as Brazil's top foreign investor, accounting for a little more than 17% of the country's FDI stock. But the trend lines tell the real story. Between 2023 and 2024, Chinese investment in Brazil surged 113%, while U.S. investment growth barely registered, at 0.057%, according to data cited by The Diplomat.

This divergence matters more than the totals. Without new financing streams from Washington, Brazil will increasingly depend on China to fund infrastructure, power grids, ports, and automotive manufacturing. That dependence becomes leverage. The deeper Brazil's supply chains intertwine with China's, the more likely Brasília is to align with Beijing's preferences in global debates—even as U.S. officials insist Latin America is central to Trump-era foreign policy.

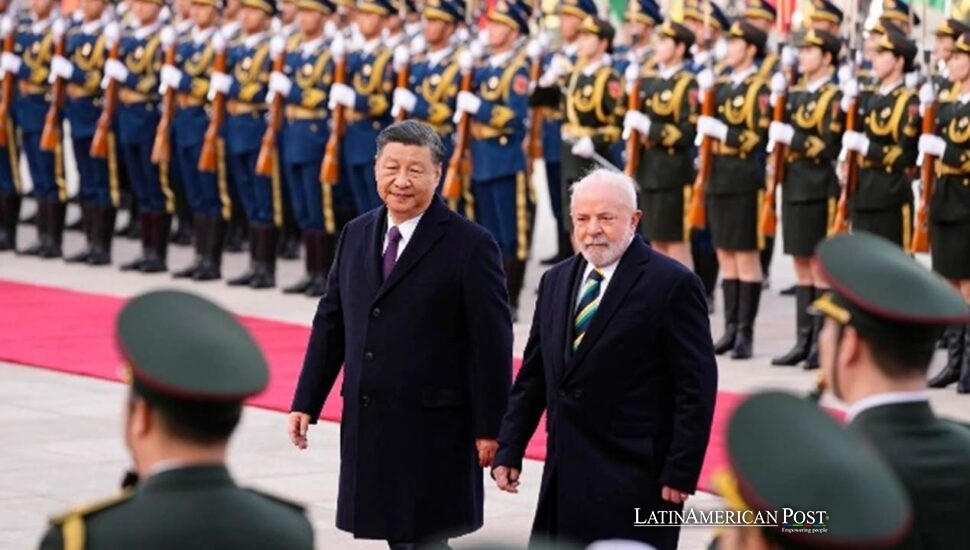

For President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, this shift aligns with a revived foreign-policy doctrine: "active non-alignment." The approach emphasizes autonomy, multilateralism, and South-South diplomacy. In practice, it means treating China not as a rival but as a strategic partner. During his 2023 trip to Beijing, Lula publicly supported settling trade in local currencies instead of dollars, signaling enthusiasm for China's de-dollarization projects—an idea that deeply worries Washington but delights Beijing.

For Lula, China offers political prestige and diversified economic options. For China, Brazil offers something rarer: a diplomatic and logistical gateway into Mercosur, the trade bloc that shapes the rules of commerce for much of South America.

BYD, Mercosur rules—and pressure on Taiwan's last allies

No example illustrates China's Brazil strategy better than BYD. The electric-vehicle giant chose Camaçari, in Bahia, as the home of its first complete manufacturing base outside China—on the ruins of a shuttered Ford plant. The factory isn't just for Brazil. It is meant to be an export hub for the entire region, shipping cars to Argentina, Uruguay, and beyond. BYD's sales to Brazil skyrocketed 327.7% in 2024, proof that Chinese brands have shed their old "cheap and unreliable" stigma, The Diplomat reports.

The regulatory structure of Mercosur supercharges this shift. Under bloc rules, a product can contain up to 45% non-Mercosur components and still count as regionally made. So, a BYD car built in Bahia with Chinese parts can be legally stamped "Made in Brazil"—and flow into neighboring countries at preferential tariffs.

This detail has significant consequences. It gives Chinese-Brazilian goods an open door into Paraguay, one of the last countries in the hemisphere to recognize Taiwan. As Brazilian-made Chinese products become central to Paraguay's consumer market, Taipei's economic leverage—the backbone of its diplomatic ties—begins to erode. The Diplomat warns that over time, Paraguay's calculus may shift, not because of ideology, but because its economy becomes tied to Chinese-Brazilian supply chains.

If Taiwan loses Paraguay, its footprint in Latin America would shrink to near zero.

Energy, Itaipu, and the quiet shift in regional power

Some of the most consequential changes are happening far from the public eye—in the wires, dams, and substations that power Brazil and its neighbors. A study cited by The Diplomat found that of the $4.8 billion in Chinese investment that flowed into Brazil in 2024, 34% went to the electricity sector, 25% to oil, and 14% to automobiles.

China's State Grid and China Three Gorges, already major players in Brazil's energy sector, now control or supply key components of transmission networks and hydroelectric projects. This puts Chinese engineering standards, financing, and technology deep inside Brazil's most strategic infrastructure.

The implications extend beyond Brazil. Paraguay and Brazil jointly manage the Itaipu hydroelectric dam, which supplies about 90% of Paraguay's electricity. China has no ownership stake in Itaipu. Yet as Brazil grows more dependent on Chinese suppliers for grid equipment, modernization, and financing, Chinese influence could shape decisions on upgrades, regional distribution, and long-term planning.

The Diplomat suggests this could indirectly constrain Paraguay's energy sovereignty, even without a single Chinese shareholder—an example of how influence now flows through supply chains rather than formal ownership.

Zoom out, and the pattern sharpens. Chinese companies are securing footholds in sectors that determine who controls the hemisphere's future: electric vehicles, rare earths, lithium batteries, power grids, infrastructure financing, and digital ecosystems. Brazil is becoming the centerpiece of that map.

For Washington and Taipei, the response so far has been tepid. A U.S.-Taiwan Partnership in the Americas Act shows intent but little muscle. Analysts interviewed by The Diplomat warn that, unless it leads to real investment in digital infrastructure, energy, and supply-chain resilience, the hemisphere's economic gravity will continue to drift toward Beijing.

Because China's rise in Brazil did not arrive as a headline—it came as a power plant contract, an EV factory, a ride-hailing app, a surge of investment. It arrived quietly, steadily, on the factory floors and smartphone screens of Latin America's largest nation.

And now, as The Diplomat's reporting makes unmistakably clear, Brazil is becoming China's bridgehead—reshaping power across the hemisphere, one grid, one factory, and one market at a time.

Also Read: Chile’s Rightward Swerve: Crime, Borders, and the Minerals That Could Redraw the Hemispheric Map