São Paulo University’s Rise: A Win With Regional Challenges Ahead

While the University of São Paulo’s rise into the top 200 global rankings is significant, this focus on global prestige may overlook deeper educational needs and inequalities across Latin America that require urgent attention to ensure regional development.

A Limited Victory for Latin American Education

The University of São Paulo (USP) recently broke into the top 200 of the Times Higher Education (THE) global rankings for 2025, securing the 199th position and sharing the spot with prominent European institutions such as the University of Ulm and the University of Mannheim in Germany, as well as the Spanish Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. While many may celebrate this achievement as a breakthrough for Latin American education, taking a closer look at the broader implications is essential. USP’s ascent highlights the region’s educational disparities and may not bode well for the future of Latin America’s universities.

The presence of Latin American institutions in these rankings remains limited, with USP leading the way, followed by Brazil’s University of Campinas (383rd) and Chile’s Pontificia Universidad Católica (555th). Brazil contributes 61 universities to the list, Chile 29, and other nations like Mexico, Colombia, and Ecuador fall behind. While there is some representation, the overall trend reveals a significant gap between the few institutions that manage to rise in these rankings and the many that remain far behind.

This gap underscores a troubling reality: instead of celebrating the rise of individual universities, we should question whether this emphasis on global rankings serves Latin America’s broader educational and societal needs. A fixation on rankings may fuel a brain drain, perpetuate existing inequalities, and distract from the core mission of many regional universities.

The University of São Paulo’s success may give the impression that Latin American higher education is catching up with the world’s elite institutions. However, the ranking only reflects a small slice of reality. Of the 2,092 institutions listed in the global ranking, only a handful of Latin American universities appear in the top tiers. While Brazil leads the region, followed by Chile, Mexico, and Colombia, most Latin American nations still lack a significant presence in these rankings. Argentina, a country with a rich history of academic contributions, manages only eight universities on the list. Meanwhile, nations like Paraguay, Costa Rica, Cuba, and Venezuela have just one each.

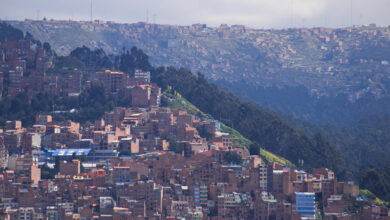

For a region as vast and diverse as Latin America, having so few universities represented—especially in the upper echelons of global rankings—raises concerns about the inclusivity and accessibility of higher education. The rise of a single institution like USP does not signal a regional trend of educational improvement. It could exacerbate the divide between top-tier institutions and the many that remain underfunded and overlooked. As the Times Higher Education rankings gain importance, governments and educational leaders may focus on elevating a few elite universities, leaving the rest behind.

In countries where educational investment is already unequal, this could deepen disparities between urban and rural institutions, private and public universities, and the few well-established centers of excellence versus the many struggling to provide essential resources for their students.

Global Rankings Highlight Regional Inequalities

While universities like São Paulo and Campinas shine in global rankings, most Latin American students attend institutions that are nowhere near these lists. These students, who represent the bulk of the region’s future professionals, entrepreneurs, and leaders, often receive an underfunded, under-resourced education and disconnected from global trends.

The emphasis on global rankings highlights and exacerbates the inequalities between Latin American countries. While Brazil has the resources and academic infrastructure to position its universities internationally, many neighbors do not. Ecuador, for instance, has only 11 universities represented, with its highest-ranked institution sitting at 739th. Paraguay and Venezuela barely make the list despite their historical contributions to Latin American intellectual life. These disparities suggest that while a few countries may successfully lift their universities into the global spotlight, the rest of the region risks being left behind.

Furthermore, the rankings themselves may not reflect the actual needs of Latin American countries. The metrics used to assess universities—including internationalization, research output, and knowledge transfer—are not necessarily aligned with the priorities of institutions serving disadvantaged or marginalized populations. In many parts of Latin America, universities play a crucial role in providing access to education for the poor, Indigenous communities, and rural populations. Their mission is not to compete with Oxford or Stanford but to offer relevant, practical education that supports local development and societal progress.

Brain Drain and the Privilege of Prestige

One danger of Latin American universities climbing the global rankings is that it may contribute to the brain drain that has long plagued the region. As institutions like USP gain global recognition, they may attract more attention from international academics and students, creating a feedback loop that further concentrates resources and talent at a few top-tier institutions. While this might elevate the status of these universities, it does little to benefit the broader region.

Latin American students who seek higher education are often drawn to prestigious universities abroad, particularly in the United States and Europe. Focusing on global rankings may encourage this trend as students and faculty chase the prestige of high-ranking institutions. Meanwhile, smaller universities, particularly those in rural or economically disadvantaged areas, struggle with brain drain. Talented students leave for opportunities abroad or in the region’s few elite institutions, leaving local universities with fewer resources to nurture homegrown talent.

This brain drain can devastate Latin American countries’ long-term development. By focusing resources on elevating a handful of universities in global rankings, governments risk neglecting the need to build robust, accessible educational systems that serve the broader population. Instead of chasing prestige, Latin American governments should prioritize policies encouraging students to stay, teach, and innovate in their home countries, helping build stronger local economies and institutions.

The Need for a New Educational Vision

The rise of USP in the global rankings reflects a broader trend of universities in emerging economies striving for international recognition. Asian universities, particularly in China and South Korea, are increasingly dominating the rankings, with 60% of new entrants coming from Asia. While Latin America lags, some may see USP’s rise as a sign of hope that the region can follow in Asia’s footsteps.

However, Latin America should consider a different path. Instead of competing in the global rankings game, Latin American universities and governments should focus on creating an educational system that meets the region’s unique needs. This means prioritizing access, equity, and local relevance over global prestige.

Latin America faces enormous social and economic challenges, including inequality, poverty, and political instability. Universities in the region have a critical role in addressing these issues, but only if they are equipped to serve their communities. Rather than striving to match the metrics of European and American institutions, Latin American universities should develop their standards for excellence—standards that reflect the region’s values and priorities.

This might mean investing in teaching and research that addresses local challenges, such as public health, environmental sustainability, and economic development. It could involve building stronger ties between universities and regional industries, encouraging innovation and entrepreneurship that benefits local economies. And it should certainly include policies that make higher education accessible to all, regardless of socioeconomic status.

The focus on global rankings is a distraction from these goals. While it’s tempting to celebrate the rise of São Paulo in the international rankings, it’s important to remember that Latin American universities’ accurate measure of success should be their ability to serve their students, communities, and countries. A more equitable and sustainable approach to education is needed—one that lifts all universities, not just the elite few.

Also read: Brazilian Left-Wing Tax Policies Are Inadequate Solutions for Economic Growth

The rise of the University of São Paulo in the Times Higher Education global rankings is not necessarily a win for Latin American higher education. While it may boost the profile of a single institution, it risks deepening regional inequalities, contributing to brain drain, and distracting from the true mission of universities in the region. Instead of chasing global prestige, Latin American universities should focus on creating an educational system that serves the unique needs of their communities and supports long-term social and economic development.