Latin America Still Sips Toddy While Us Vintage Drink’s Past Forgotten

A century after fizzing to life in frozen Buffalo, the malt-sweet drink mix Toddy has slipped from North American shelves. Yet every dawn from Caracas to Curitiba, a yellow tin still thumps on kitchen counters, stirring memories—and milk—into motion.

From Snowy Buffalo to Tropical Breakfast Rituals

The recipe was born in 1919 when food-service entrepreneur James William Rudhard blended cocoa, barley malt, and powdered milk so US soldiers could ladle something hot on midnight guard shifts. Stateside shoppers liked it, but Rudhard’s masterstroke was hiring Puerto Rican salesman Pedro Erasmo Santiago. Santiago saw beyond Manhattan drugstores; he pictured South America, where thick chocolate drinks anchored breakfast. By 1928, he had secured continental rights, ferried pallets of mix through the Panama Canal, and planted a factory on Buenos Aires’ south docks.

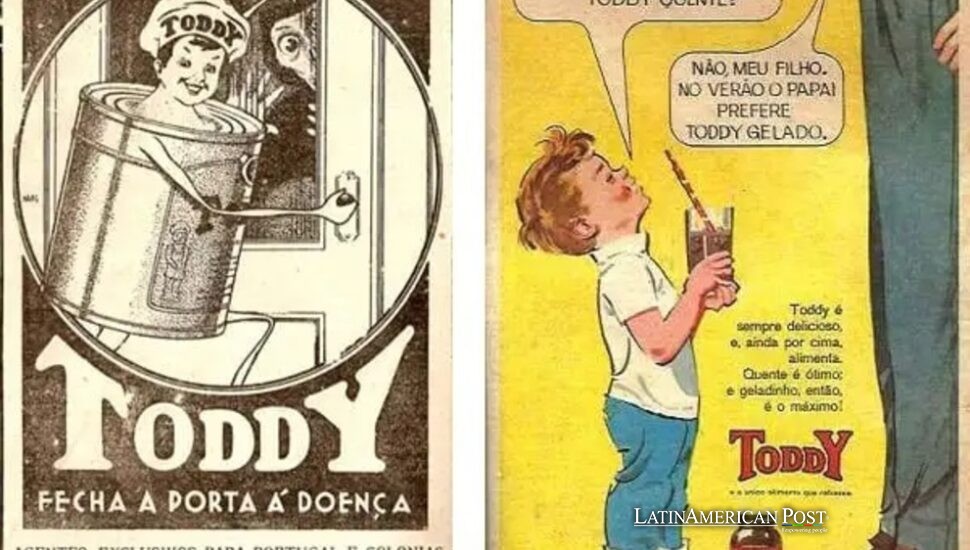

An early Argentine poster promised, “dos cucharadas de Toddy valen seis huevos.” The claim was marketing puff, yet parents believed it. Schoolchildren began the day with steaming mugs, and within a decade, the jingle “Toddy—fuerza al instante“ crackled from radios in Paraguay, Uruguay, and Chile.

When the Bronx Forgot, Buenos Aires Remembered

Back home, the 1950s breakfast aisle turned into a street fight. Nestlé unleashed Nesquik, and Cereals Inc. rolled out Carnation Instant Breakfast. Supermarkets thinned Toddy’s shelf space until the brand vanished like yesterday’s Ovaltine. But south of the Río Grande, the yellow canister was already family.

In Venezuela, food historian Vanessa Rangel remembers her mother tapping the tin against the rim of a glass so the powder slid in neat waves. “If the clink didn’t echo through the house, we thought we’d overslept,” she laughs. Sociologists from the Universidad de Los Andes later documented the ritual: mix, stir, gulp, school—an urban bridge between Indigenous cacao culture and fast-modernizing cities.

By the 1970s, the brand doubled down on Brazil, where São Paulo executives shrank the serving to a single-dose “Toddynho” box—the first shelf-stable chocolate milk many children ever carried in a lunch sack. The package featured a cartoon cow so wide-eyed she looked permanently over-caffeinated. Parents bought; kids begged; rivals howled.

Latin American Post Archive

How PepsiCo Kept the Spoon Spinning

When PepsiCo purchased Latin rights in 2001, analysts expected a phase-out. Instead, the beverage giant turned Toddy into an R&D sandbox: cereals in Caracas, ice-cream bars in Maracaibo, chocolate-chip “Galletitas Toddy“ in Buenos Aires, and protein-fortified powder for Brazilian gyms. Market trackers at Euromonitor now value Latin America’s chocolate drink segment at nearly US $10 billion, with Toddy and Nesquik neck-and-neck. Even Covid lockdowns helped; Brazilian supermarkets logged 30 percent spikes in powdered drink sales as families replicated cafeteria mornings at home.

Social media kept the brand restless. Venezuelan baristas lace cold brew with Toddy powder; Brazilian bakers fold it into fudgy brigadeiros; Argentine TikTokers still bicker over whether milk or mix goes first, a debate as fierce as pineapple on pizza. Confronted with new front-of-pack sugar warnings, PepsiCo released a reduced-sugar Toddy in Chile and a soy-based version for lactose-sensitive Colombians. “Nostalgia tastes sweet,” brand manager Camila Ferreira admits, “but it must also taste like tomorrow.”

Sweet Resilience in a Changing Cocoa World

Toddy’s endurance mirrors Latin America’s indelible link to cacao—a crop carried by Olmec traders four millennia ago, exploited by colonial powers, and now curated by chefs chasing single-origin prestige. A humble malt powder might seem trivial in that grand narrative, yet it shows how food traditions migrate, settle, and evolve.

Will the mix ever leap back across the equator? PepsiCo executives leave the door ajar, hinting at “select U.S. Hispanic markets.” But American aisles brim with oat-milk lattes and collagen cocoas; Toddy would compete not with memories but with macros. Until then, it remains a Latin talisman: a scoop of history clinking against glass, dissolving into warmth.

Also Read: Panama Port Paralysis: How the Chiquita Walkout Stalled Banana Exports

Tomorrow morning, another spoon will strike a mug in Bogotá, and a child will taste the same malted sweetness her grandmother once gulped before walking to a one-room schoolhouse. Brands come and go, but some ride steam from the stove straight into folklore—and they stay there across a continent.