Latino Entrepreneurs Feel the Pinch as Trump’s Promises Get Costly

They backed Donald Trump in 2024 for cheaper lives and tighter borders. Now Latino business owners say the math is turning against them, squeezed by tariffs, rent, and raids that empty parking lots faster than any recession headline can.

Prices Rise, Patience Falls

In the months after 2024, many Hispanic businesspeople who had leaned toward Trump did so with the practical faith of shopkeepers and strivers: the belief that an administration that talked incessantly about the economy would make daily life feel lighter. Instead, they describe an era where the public numbers and the private receipts refuse to match, and where the same two forces that moved them toward him—economic anxiety and immigration—are now dragging them away.

A recent survey of Hispanic business owners conducted by the U.S. Hispanic Business Council and shared with POLITICO reads like a ledger of disappointment. Forty-two percent said their economic situation is getting worse, while only twenty-four percent said it was getting better. And when asked what is pressing the country most, seventy percent ranked the cost of living as a top-three issue—more than double the share that chose any other concern. For a constituency that, in the organization’s final survey before the election, had leaned toward trusting Trump over then–Vice President Kamala Harris on the economy, the reversal feels personal.

“The broader Hispanic community certainly feels let down,” said Javier Palomarez, the group’s president and CEO. He framed the grievance in the blunt language of expectation: it would be one thing if immigration and the economy had not been central selling points for Trump. “On both fronts,” Palomarez said, “we didn’t get what we thought we were going to get.”

The frustration is not abstract. It arrives as higher supply costs, unpredictable margins, and customers who pause at the register the way they pause at a gas pump, waiting for a number that finally makes sense. The survey respondents’ worries are sharpened by what they blame for the squeeze: stubbornly high prices driven by Trump’s tariffs, and the economic ripple effects from immigration enforcement actions in immigrant-heavy communities. To small businesses, the economy is not a chart; it is a Saturday night dining room, a weekday lunch rush, a payroll cycle that does not forgive miscalculation.

The administration’s allies insist they are undoing damage they inherited. “Republicans are putting in the work to fix the Bidenflation mess we inherited,” said Delanie Bomar, a spokeswoman for the Republican National Committee, pointing to efforts from inflation to housing. But among Latino business owners, that argument can land like an explanation that arrives after the bill: maybe true in a speech, less comforting at the counter.

Raids at the Doorstep

If tariffs and costs are the slow bleed, immigration enforcement is the sudden shock. Monica Villalobos, president and CEO of the Arizona Hispanic Chamber of Commerce, told POLITICO about a South Phoenix restaurant battered by the two-sided pressure of tariffs and labor shortages. Then, she said, a series of ICE raids in the parking lot in front of the business changed everything at once. Customers stopped coming. Workers stopped showing up. The owners shut down for several days—not because their food had changed, but because the atmosphere had.

“We certainly do sense that our members — our clients in Arizona and across the country — feel a sense of betrayal by this administration, given its excessive overreach,” Villalobos said. She predicted the political consequences will follow the economic ones. “Now that we’ve had a taste of [the Trump administration],” she said, “I think you’re going to see a big shift [in the vote].”

That shift has numbers behind it. In 2024, Trump won forty-eight percent of self-described Hispanic or Latino voters, the highest mark for a Republican presidential candidate in at least a half-century, an outcome driven largely by pocketbook dread. Now, polling described in the text shows his approval among Latino voters falling as satisfaction with both the economy and immigration enforcement drops.

In a November POLITICO Poll, forty-eight percent of Hispanic respondents said the cost of living is “the worst I can ever remember it being,” and sixty-seven percent said it is the president’s responsibility to fix it. A November Pew Research poll found about sixty-eight percent of U.S. Hispanics saying their situation is worse than a year ago, and just nine percent saying it is better. In that same set of findings, sixty-five percent disagreed with the administration’s approach to immigration, and a majority—fifty-two percent—said they worried they, a family member, or a close friend could be deported, a ten-point increase since March. In a recent The Economist/YouGov poll, Trump’s favorability among Hispanics sat at twenty-eight percent, thirteen points lower than February of last year.

“Small business owners are becoming a swing constituency, when you think about the midterms coming up,” said Tayde Aburto, president and CEO of the Hispanic Chamber of E-Commerce. The reason, Aburto argued, is not some sudden cultural conversion. “And not because their values have changed—it’s just because their costs did.”

A Swing Vote with a Receipt

The early electoral tremors show up in local returns, where the political winds can feel less like ideology and more like weather—shifting, immediate, hard to deny. In Passaic County, New Jersey, Latinos voted narrowly for Trump in 2024 but then backed Democratic Governor-elect Mikie Sherrill by double digits in November. In Miami, where over seventy percent of residents are Hispanic, voters elected a Democratic mayor last month for the first time in twenty-eight years, according to the text. Christian Ulvert, a Democratic strategist and adviser to newly elected Miami Mayor Eileen Higgins’ campaign, described those outcomes as a referendum on Trump’s economy—less about party identity than about whether families feel safer, steadier, and more able to breathe.

Meanwhile, on the Republican side, even sympathetic voices describe the enforcement dragnet catching people whose lives have already sunk roots. Joe Vichot, the Republican Party chair in Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, said he knows many Hispanic Republicans in Allentown who support curbing illegal immigration and fighting crime. But he also sees “stories of people who have been here for ten years or more with their family” who have never been legal and are now caught up in the deportation system. “There should be a way to find some type of common ground where that won’t happen,” he said.

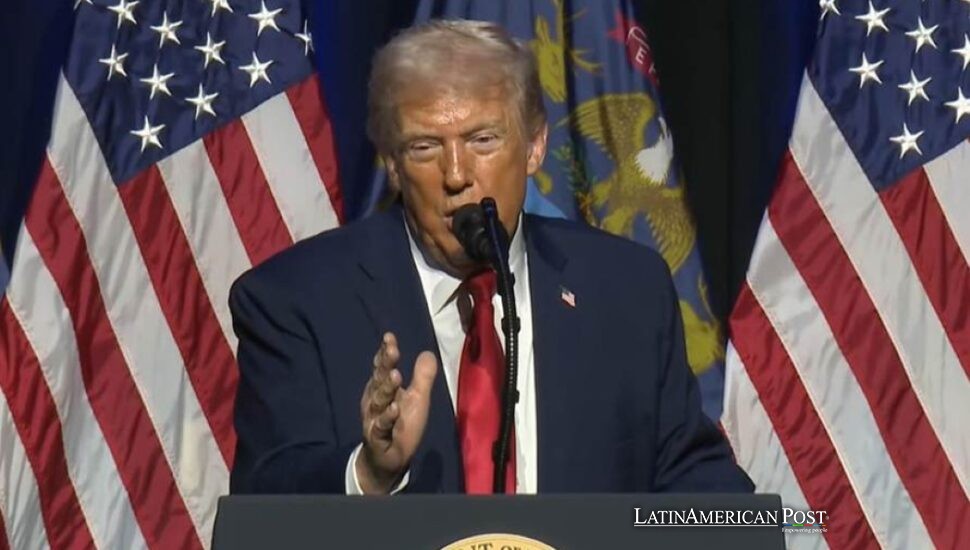

The White House has tried to blunt the sour mood by putting Trump and Vice President JD Vance on the road with speeches on affordability in working-class areas, including Vance’s Dec. 16 stop in Lehigh County, which includes the Hispanic-majority city of Allentown. They have argued the economy deserves an “A+++” and pointed to a December consumer price index report released Tuesday showing inflation rising more slowly than expected. In Detroit on Tuesday, Trump declared that his administration had “rapidly and very decisively” ended the prior president’s “colossal catastrophe,” claiming “almost no inflation and super high growth.”

But for the people who price the tortillas, weigh the meat, and calculate payroll by hand, “slower” inflation can still mean high prices that never came back down. Massey Villarreal, a business executive in Houston and a former chair of the Republican National Hispanic Assembly, put it plainly: the inflation figure does not translate when you are staring at the grocery bill and the cost of hamburger meat.

And Palomarez offered a warning shaped by recent memory, comparing today’s rosy macro talk to the previous administration’s insistence that the post-Covid economy was healthy even as sentiment fell. While leaders argued over GDP and job growth, he said, people were worrying about rent, gas, and eggs. “And we’ve got kind of the same thing here,” he said.

In Chicago, where some of the most-publicized immigration enforcement occurred last year, Hispanic-run businesses have been hit hard. Sam Sanchez, CEO of Third Coast Hospitality, said 2025 was the hardest stretch of his four decades in the restaurant business, aside from the COVID pandemic. The political sting, he suggested, is that the pain lands directly on the community that helped create Trump’s forty-eight percent Latino showing.

“It sends a really negative message to the forty-eight percent of Hispanic voters that voted for President Trump,” Sanchez said. “Everything’s just starting to fall apart.”

Also Read: Mexican CIE Turned Live Entertainment into an Empire and Ticket Gold