Harlem’s Latin Heartbeat Plays on for Eddie Palmieri

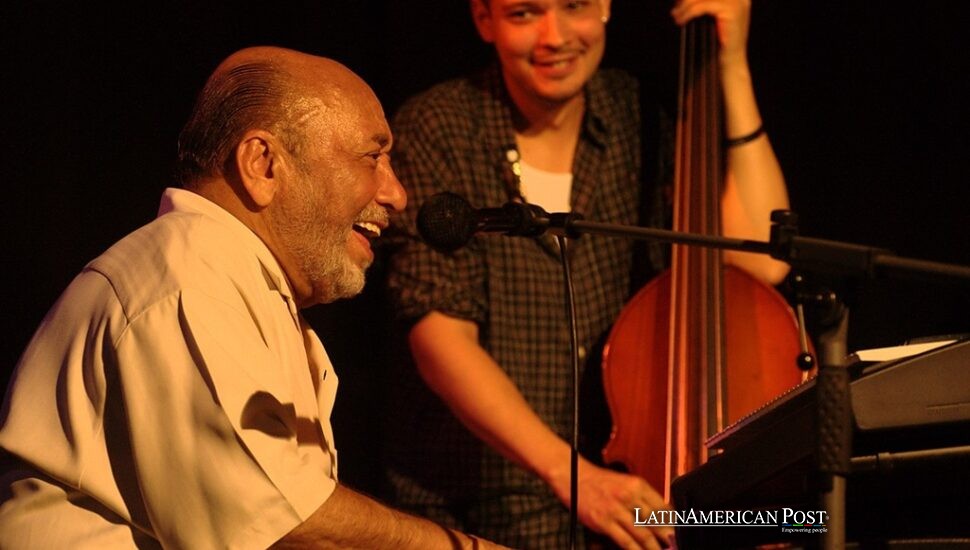

In the warm pulse of El Barrio, one day after Eddie Palmieri’s passing at 88, the air was thick with his piano’s voice—notes spilling into the streets that raised him, carrying both grief and gratitude in every chord.

A Morning Wrapped in Music and Memory

On the corner of 116th Street and Lexington Avenue, the unmistakable strains of Verdict on Judge Street floated from El Barrio Music Center, the last Latin music store still standing in Manhattan. Inside, owner Reynaldo Meléndez moved between the register and the turntable, helping customers who weren’t just buying records—they were confirming the loss of a man whose music had been the soundtrack to their lives.

“For hours, people have been coming in asking, ‘Is it true? Do you have his music?” Meléndez told EFE, his voice carrying the weight of both pride and mourning. For 35 years, his shop had endured the slow erasure of El Barrio’s musical landmarks, holding out against streaming platforms, real estate pressures, and the passing of the very artists whose records lined his shelves.

Palmieri, who won ten Grammys, had grown up only blocks away. Now, shoppers thumbed through his CDs or pulled t-shirts from a rack—each one emblazoned with his image, fingers frozen mid-flight above the keys. The photos showed him alongside giants: his brother Charlie, “El Gigante de las Negras y las Blancas,” and fellow Fania All Stars like Papo Lucca and Larry Harlow.

The Last Sun of Latin Music

“We’ve lost a legend, a pillar of our music—one of the last,” Meléndez said, spreading out Palmieri’s albums across the counter: the fierce brass of Justice, the elegant sway of Lindo Yambú. This jazz-infused salsa had made him impossible to pin down.

For Meléndez, the best tribute was the music itself. Palmieri’s compositions poured through the open doorway, rolling down the sidewalk into the hum of the neighborhood. His sound—equal parts clave rhythm and bebop daring—was born in the Puerto Rican migration wave of the 1950s, when El Barrio’s streets throbbed with a new hybrid of salsa, jazz, plena, and bomba.

Meléndez could not pick a single favorite. Still, he named Vámonos pa’l monte, Muñeca, and Puerto Rico as essential—each track a collaboration with voices now gone, like Ismael Quintana and Lalo Rodríguez. “They’re all gone now,” Meléndez said softly, “but when the needle drops, they’re still here.”

A Genius in the Neighborhood

One of those who stopped in was Enrique Carrillo, a longtime El Barrio resident. “He’d come by the neighborhood sometimes,” Carrillo told EFE, “and he was very accessible. He’d stop, talk, listen—no ego.”

Palmieri’s accessibility didn’t soften his edge as an artist. Writer and historian Aurora Flores called him “never predictable—controversial, but a co-creator and defender of Latin music.” He pulled folkloric rhythms like Puerto Rican plena and bomba into his arrangements, expanding Afro-Caribbean music without diluting its roots.

Flores remembered phoning producer Harvey Averne after hearing the news. Averne had produced El Sol de la Música Latina, Palmieri’s first Grammy winner, and written liner notes for Sentido. “The world has lost another creative artist, bandleader, composer, and the great artist of Latin music,” he told her. Averne had been the first to call Palmieri “the sun of Latin music,” a title that stuck because it fit—the way his music lit a room from the first chord.

Naming the Street, Keeping the Light

Now, a proposal is moving through the city to rename East 112th Street for both Eddie and Charlie Palmieri. Charlie’s name has already graced the block since 2014; soon, the brothers may be linked there forever, in the place where they first learned the craft that would change the sound of two continents.

But on this day, the tributes weren’t plaques or official proclamations. They were in the heads bobbing gently to a horn break, in the strangers trading memories over the counter at Meléndez’s shop, in the way a Palmieri montuno could momentarily dissolve the city’s edges until all that remained was rhythm.

El Barrio has weathered waves of migration, poverty, gentrification, and loss. Yet, for a few hours, Palmieri’s music held the neighborhood in something like the old unity—people laughing in two languages, swaying in place, carrying records home like treasures.

Also Read: Peruvian Titan Bids Farewell: Mario Vargas Llosa’s Influence

Eddie Palmieri may have left the stage, but in the neighborhood that shaped him, the sun still shines—its rays in every tumbao, its warmth in every piano run that drifts out of a record shop and onto a Harlem street.

Quotes and interviews courtesy of EFE.