Titanic’s Overlooked Stories of Latin American Tragedy

The Titanic disaster of 1912 is one of the most infamous maritime tragedies in history, yet the stories of Latino passengers who died or survived remain largely unacknowledged. The family heritage and bravery of Latino Titanic passengers emerge through their stories that became submerged in the Atlantic Ocean.

A Global Catastrophe with Hidden Dimensions

When the RMS Titanic struck an iceberg on April 15, 1912, the world reeled. Newspapers across continents heralded the tragedy of a vessel deemed “unsinkable,” echoing shock and sorrow for the more than 1,500 lives lost. It was a singular moment in modern history—so widespread in impact and publicity that many called it the first truly global tragedy. Yet amid the clamor of headlines, the untold stories of Latin American passengers faded from view.

The Titanic epitomized a world on the move: millionaires, immigrants, students, and working-class dreamers mingled in a temporary microcosm of society. Driven by education, business, or family ties, a handful of Latino passengers boarded the ship. Several passengers enjoyed first-class accommodation, whereas others managed to secure spots in second or third class with aspirations of creating better opportunities abroad. The personal histories of these travelers remain mostly undocumented because the stories of British, American, and European travelers overshadowed them. Over a century later, the fragments that remain—letters, recovered suitcases, or genealogical traces—offer insight into a dimension of Titanic history that is seldom explored.

Argentinian Hopes and Unfinished Journeys

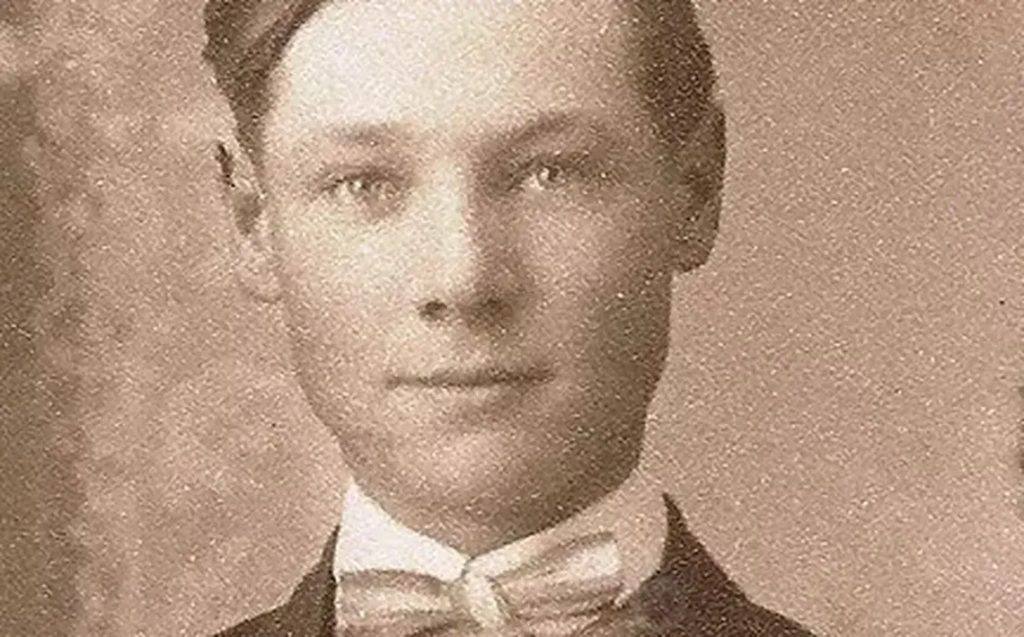

Among these overlooked stories is that of Edgar Andrew, a teenager from Río Cuarto, Córdoba, Argentina. At 16, Edgar moved to England to study, yet he never quite relinquished his love for farmland back home. When he received an invitation to his brother’s wedding in the United States, he planned to sail on a different ship, the Oceanic, but a coal strike forced him to switch tickets. Thus, he found himself aboard the Titanic.

Tragically, Edgar did not survive, and his body was never recovered. However, in a 2000 expedition to the Titanic’s wreck site, divers discovered his suitcase. Inside were letters, shoes, slippers, and an inkwell—intimate tokens of a young life interrupted. Back in Argentina, an online museum dedicated to preserving Edgar’s memory now ensures his story is not forgotten. This recovered item demonstrates how one piece can reveal the story of a person overshadowed by major historical events.

Violeta (Violet) Jessop lived a life that seemed written by fate itself. Violet Jessop moved to England from her birthplace in Bahía Blanca, Argentina, after her father passed away. She became a stewardess on the Titanic when she reached 24 years old. On that fateful night, as lifeboats filled in desperate haste, Violet was tasked with assisting non-English speakers on deck. She was handed a baby just before boarding a lifeboat; once rescued by the Carpathia, a frantic mother snatched the child from her arms and vanished. Remarkably, Violet went on to survive yet another maritime disaster: she served as a nurse aboard the Britannic (the Titanic’s sister ship) during World War I. The Britannic struck a mine and sank, but Violet outlived that ordeal too, ultimately passing away in 1971. Her memoir, published posthumously, provides a rare firsthand account of two historic sinkings—and the fleeting moments that define who gets to live and who does not.

Mexican and Uruguayan Legacies Left at Sea

One of the most poignant untold tales is that of Don Manuel Ramírez Uruchurtu. An influential lawyer from a wealthy Mexican family, Don Manuel had enjoyed significant stature under President Porfirio Díaz’s regime. In the aftermath of political upheaval, he traveled to France and then eventually boarded the Titanic in Cherbourg for his return journey. The story goes that Don Manuel forfeited his lifeboat seat to another passenger during the Titanic disaster on April 14, which led to the creation of the “The Titanic’s Gentleman” legend as his body remained lost at sea. Don Manuel’s story from Mexico demonstrates how folklore and historical memory blend together to create powerful yet invisible tributes to honorable sacrifice.

Uruguay’s own share of Titanic tragedies includes Ramón Artagaveytia, a 72-year-old first-class passenger who had previously endured another maritime mishap four decades earlier. This time, fortune did not favor him. Though his body was later recovered, it remains a mystery why he did not claim a lifeboat seat commonly afforded to first-class passengers. His story underscores how no amount of wealth or status could guarantee safety on a doomed ship.

Likewise, Francisco and José Pedro Carrau—uncle and nephew hailing from a prominent Uruguayan family—boarded in Southampton as first-class passengers. Francisco served on the board of directors at Carrau & Co., while 17-year-old José Pedro was just beginning to carve out his path in life. Neither survived, and their remains were never found. Their stories, almost forgotten in mainstream Titanic lore, nonetheless reflect heartbreak that resonates across Latin America, reminding us that transatlantic voyages were fraught with risks regardless of class or background.

A Wider Range of Latin American Tragedies

The Titanic’s catastrophic sinking, often hailed as the ultimate early-20th-century drama, has overshadowed countless personal journeys that converged aboard the ship. Wealthy financiers and Hollywood movies have kept the focus on first-class ballrooms and final waltzes on the top deck. The steerage residents, with their Irish folk music to Argentinian hopefuls starting new chapters, demonstrated the unique cultural essence each passenger possessed. The extensive Latin American narrative weaves together global stories that surpass complexity beyond what popular retellings typically depict.

Such forgotten tragedies are not unique to the Titanic. Throughout Latin America, stories of struggle, migration, and resilience abound, though many remain unchronicled on the world stage. Indeed, each retelling of the Titanic often highlights universal themes—social divisions, human hubris, and fleeting heroism—while eclipsing the smaller but equally significant narratives, like those of Edgar Andrew, Violet Jessop, or Don Manuel. It is possible to honor individual bravery plus the connections between large-scale disasters once silent stories become known. At sea or on land, it affects common memory. If we allow these stories to be heard, they can bring people together.

Museums and online archives along with certain historians work to document often forgotten elements of the Titanic disaster. The recovery of belongings from the sunken ship caused more interest in its less known passengers. It offers historians the opportunity to add complexity to a story of the past century. Each photograph, suitcase, or letter shows the reality of a varied and interconnected group. Latin American travelers faced the same mortal danger and the same sad final moments as fellow passengers.

Also Read: Peru’s Genius: Vargas Llosa’s Cinematic and Theatrical Legacy

The Titanic people often focus on its size, design, and disastrous end. Yet, within that epic scale lies the simpler human quest for belonging and opportunity, in a cherished letter or a second-hand ticket switched at the last moment. That quest led a handful of Latinos onto the decks of the most famous ship in the world, where their stories sank beneath the waves alongside the illusions of invincibility. Only by unearthing these lesser-known tales can we begin to see the Titanic not as a monolith but as a mosaic of hopes, dreams, and losses—Latin American voices included.