Argentina Unveils Fossil Discovery Evoking Ancient Underwater Worlds

Some 200,000 years ago, an eel-like fish swam in the prehistoric rivers of central Argentina. Now, paleontologists at San Pedro’s museum have unearthed a fossil vertebra from that rare species, shedding light on a vanished ecosystem of mysterious freshwater giants.

A Rare Glimpse into Ancient Waters

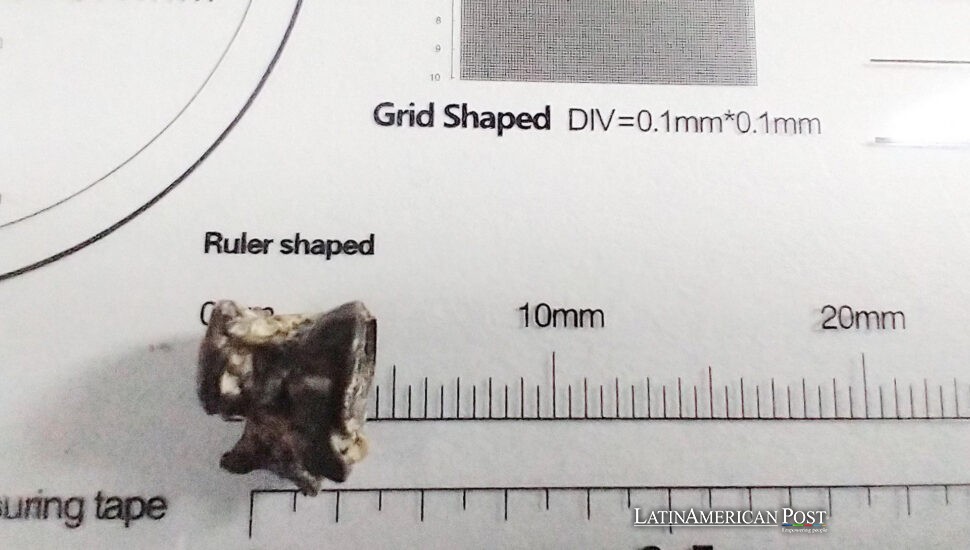

In a region known more for the bones of mammoths and giant sloths, the recent discovery of a tiny vertebra has reignited interest in Argentina’s paleontological treasures. According to researchers from the San Pedro Paleontological Museum, this mere fragment once belonged to a fish of the Synbranchus genus—relatives of modern swamp eels that lurk in murky waters today. In a statement to EFE, museum director José Luis Aguilar revealed, “When we spotted the small fossilized piece, we were excited because fish fossils in the Pampa region are extremely scarce. This new record enriches our understanding of the prehistoric environment.”

Excavations took place in a paleontological reserve called Campo Spósito, about eight kilometers from the city of San Pedro in Buenos Aires province. While the site has previously yielded remains of giant ground sloths, towering glyptodonts, and other megafauna, fish fossils remained elusive. Aguilar further noted that this newly discovered fish likely measured about 1.2 meters, a striking size for ancient eel-like species. “We’re slowly piecing together an entire tapestry of that habitat,” he added, “from huge mammals to now a substantial aquatic predator.”

Sergio Bogan, an ichthyology expert at the Bernardino Rivadavia Museum of Natural Sciences, assisted in classifying the bone. In the museum’s official statement, he deemed it “a truly intriguing find,” underscoring the possibility of future revelations. “Once a single fish genus is discovered,” Bogan told EFE, “there’s always a chance more aquatic fauna might surface.”

The World of Ancient Synbranchus

Though modest in size, Synbranchus fish can reveal powerful insights. Fossils from this genus have surfaced sporadically in Argentine rivers like the Quequén Salado, Luján, and Reconquista. Nonetheless, such evidence remains patchy, hinting at a largely uncharted prehistoric aquatic realm. The uncovered vertebra features a distinctive morphology reminiscent of modern swamp eels, which favor hidden habitats in freshwater streams and marshes. Bogan explained, “These fish are typically nocturnal, with slender bodies and specialized gills, perfect for turbid wetlands. Their fossils can shed light on how ancient climates shaped local waterways.”

Ancient rivers once crisscrossed what is now farmland in Buenos Aires province, supporting a dense web of aquatic life. With the region’s climate shifting over millennia, river courses changed or vanished, preserving pockets of skeletal remains beneath layers of silt. The new fossil’s 200,000-year timescale situates it in the mid-Pleistocene, a fascinating epoch marked by pulsating glaciations, large mammals roaming plains, and mild wetlands teeming with amphibians and fish. This interplay of flora and fauna gave rise to unique ecological niches, many of which left only faint imprints in geological strata.

For museum director Aguilar, the discovery fosters fresh interpretations of local biodiversity: “Synbranchus adds another missing piece. We usually talk about giant armadillos and mastodons, but rarely mention the watery predators or small creatures. Every new genus deepens our sense of the region’s past.” He hopes further digs at Campo Spósito can unearth additional species, clarifying relationships between fish populations, water levels, and shifts in surrounding vegetation.

Preserving Past for the Future

Beyond its scientific charm, the “eel fish” vertebra underscores the importance of preserving lesser-known paleontological sites in Argentina’s farmland. Geologists confirm that while the mammoth skeletons of Patagonia and the dinosaur footprints of the northwest hold broad appeal, smaller local reserves like Campo Spósito often provide crucial knowledge of different eras and habitats. “They’re the hidden gems,” Aguilar said. “We must protect them against the threats of urban sprawl or agricultural expansion that can destroy layers of history.”

Officials in San Pedro, a modest city near the Paraná River, hope the find elevates heritage tourism. Families already visit the local museum to marvel at giant ground sloth bones and glyptodont shells. Now, staff display the fish vertebra alongside diagrams illustrating prehistoric wetlands and the fish’s probable appearance. Some children find it hard to believe an eel thrived here before farmland or roads existed. For them, the battered vertebra exemplifies the mesmerizing puzzle of life long gone.

In tandem with a coalition of paleontologists and local authorities, the museum aims to expand excavation areas, betting that more aquatic fossils lurk unseen. Bogan remains optimistic: “When an environment is so rarely studied, each discovery paves the way for more. It sets a precedent that yes, fish remains can be found in Pampa.” The team encourages other amateur fossil hunters to immediately report suspicious fragments rather than keep them as curios—a step crucial for both legal compliance and scientific integrity.

Also Read: Chile Fights Looming Peril for Humboldt Penguins’ Future

In the grand scheme, this singular bone depicts a watery saga from 200,000 years ago, an era that shaped landscapes and species. Far from being a mere curiosity, it reminds modern Argentines that watery life teemed across their region, forming a dynamic ecosystem supporting creatures large and small. As the beep of excavation tools recedes into farmland quiet, the scientists carry forward a simple but profound mission: to reassemble chapters from Earth’s evolving story. And each subtle discovery—be it a chunk of jaw or a single vertebra—invites everyone, from local kids to globe-trotting researchers, to imagine a deep-time realm where an eel glided under star-lit wetlands, long before roads or farmland existed.