How Arhuaco Youth Are Using VR to Protect Colombia’s Sacred Heart

High in Colombia’s Sierra Nevada, Arhuaco youth like Sey’arin Villafaña are using virtual reality and AI to reimagine ancestral stewardship—offering immersive journeys into Indigenous landscapes without trampling sacred ground, and inviting the world to listen without intruding.

Turning Sacred Territory Into a Digital Portal

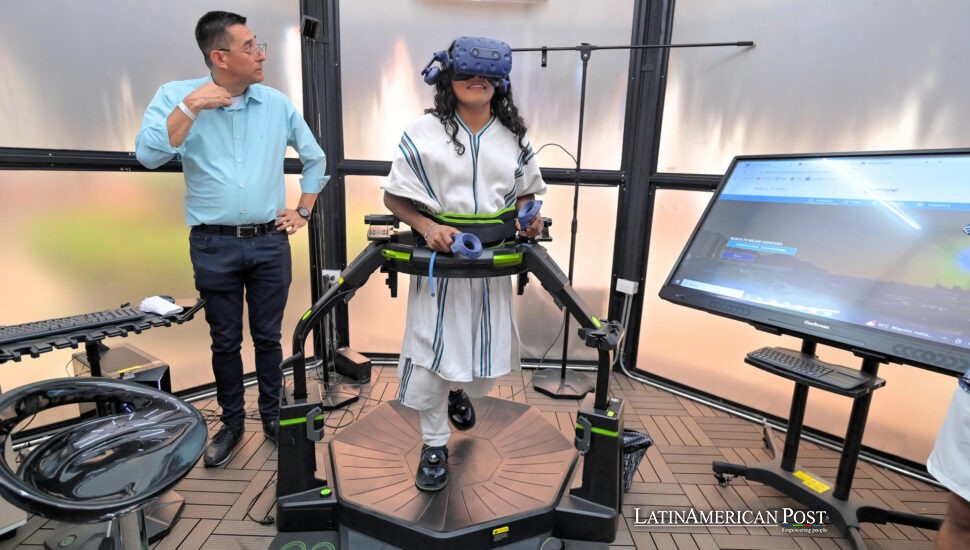

In a sleek new center near the Caribbean coast, visitors strap on headsets and find themselves transported—not to a theme park or space station, but to the cool, misty trails of Colombia’s Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. Through 360-degree visuals and spatial audio, they hear the voice of Sey’arin Villafaña, 22, an Arhuaco leader in traditional tunic and tutusoma hat, guiding them past hidden lagoons and ancient stone terraces.

“This is a way for people to connect with our territory,” Sey’arin told EFE. “But without stepping where they shouldn’t.”

The VR experience, housed inside Santa Marta’s Immersive Tourist Experience Centre, allows travelers to explore high-altitude páramos, ancestral trails, and the Arhuaco cosmovision without risking damage to fragile ecosystems or sacred sites.

The Arhuaco people, who consider the Sierra Nevada the “heart of the world,” have long guarded its peaks and waters from outside intrusion. Now, they’re using digital tools to extend that guardianship. “We can’t close the door to visitors,” Sey’arin says. “But we can invite them differently.”

Researchers at the Sorbonne’s Tourism Lab suggest that this approach may provide a model for UNESCO Biosphere Reserves worldwide: reducing foot traffic, preserving cultural authenticity, and fostering emotional connections from a respectful distance.

Avenhub: Tech and Ancestry Interwoven

The VR project is part of Avenhub, a national innovation program backed by Colombia’s Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation, in collaboration with the University of Magdalena and local governments.

Its mission: reimagine tourism by mixing neuroscience, AI, and Indigenous knowledge.

Project director Paula Villa told EFE that her team conducted fieldwork in over 3,000 households across 14 municipalities, ranging from the banana fields of Aracataca, where Gabriel García Márquez grew up, to the jungle-wrapped ruins of Ciudad Perdida.

Inside each Immersive Centre, visitors explore simulations of 42 different Colombian heritage sites. Sensors track brainwaves and heart rates to measure emotional engagement. “We use those signals,” Villa explains, “to fine-tune how people ‘feel’ the journey. The goal is to spark real-world curiosity.”

At the MIT Media Lab, researchers studying “affective immersion” have praised similar tools for expanding access and empathy in digital tourism, but also stress the need for clear data ethics and informed consent. Villa’s team says they’ve addressed this by keeping biometric data anonymous and optional.

Still, the real frontier may not be technical—it’s narrative. And that’s where Sey’arin and his peers are leading.

Access Without Erasure: Who Gets to Walk the Mountain

For many would-be travelers—especially the elderly, disabled, or low-income—the Sierra Nevada has long felt out of reach. A single hike to Cabo San Juan in Tayrona National Park can take two hours each way, often over steep and uneven terrain.

That’s why Ana Isabel Cucunubá, an Emberá-descended guide at the center, says virtual experiences aren’t just gimmicks. They’re invitations.

“Some of our visitors are in wheelchairs,” she told EFE. “They’ll never walk those trails. But here, they do.”

Inclusive-tourism researchers at the University of Barcelona say these simulations offer more than previews—they provide full experiences for people otherwise excluded. They also help travelers decide before they damage: if a visitor realizes that a remote lagoon is more moving in VR than in person, they may opt not to disturb it at all.

Cucunubá notes that some participants, after their headset tour, choose to support conservation or artisan cooperatives instead of trekking. “That’s still tourism,” she says. “Just with more care.”

For locals, too, this model offers employment, without turning guides into props or elders into background color. “We’re telling our own stories,” Sey’arin says. “On our terms.”

Where AI Meets the Sacred

The Sierra Nevada is no stranger to modern pressures. Deforestation, illegal mining, and climate change threaten its future as much as disrespectful tourism. But for Sey’arin, the real danger is cultural erasure—when outside interpretations drown out Indigenous voices.

So he’s pushing further.

His team is now testing biodiversity apps powered by AI, using Arhuaco knowledge to help visitors recognize plant species and their ecological roles. They’re also exploring lithium-powered e-mobility trails for future use around the base of the Sierra, designed to have a low environmental impact.

Anthropologist Lina Gutiérrez, of the National University of Colombia, sees this as a form of “digital diplomacy.” Instead of resisting modernity, the Arhuaco are shaping it. “They’re showing that tradition and innovation don’t clash—they reinforce each other,” she said.

This model could influence everything from climate adaptation to Indigenous data sovereignty. If the community controls both the content and the code, they can steer how outsiders learn, engage, and invest.

Sey’arin’s generation isn’t just translating the Sierra for visitors. They’re protecting it—with fiber optics and with ritual, with headsets and with wisdom.

Near the Immersive Centre, tourists sip juice from bamboo cups. They’ve just “walked” the stone stairs of Ciudad Perdida, heard bird calls echoing through the cloud forest, and listened to Sey’arin explain why some rivers must never be touched.

Back in the mountains, where real trails wind up toward sacred lagoons, the elders nod with cautious hope. For centuries, outsiders have tried to conquer the Sierra. Now, at last, some are learning to enter with humility—and to leave a lighter footprint.

Also Read: Bolivian Students Forge Lithium Dreams into a Home‑Built Electric Car

Credits: Reporting and interviews by EFE with Sey’arin Villafaña, Ana Isabel Cucunubá, Paula Villa, and Lina Gutiérrez; academic context from the Sorbonne Tourism Lab, MIT Media Lab, University of Barcelona, and Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Additional data from Colombia’s Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation and the University of Magdalena.