Mexico's 'Dragon' Dinosaur Discovery Shakes Up Paleontology World

High in Coahuila, Mexico, a newly uncovered dinosaur sporting unusually extended forelimbs has been declared a “Mexican dragon.” Scientists say this bizarre species, some 73 million years old, offers further proof of Mexican dinosaurs’ remarkable but under-appreciated diversity.

Surprising New Find In Mexico

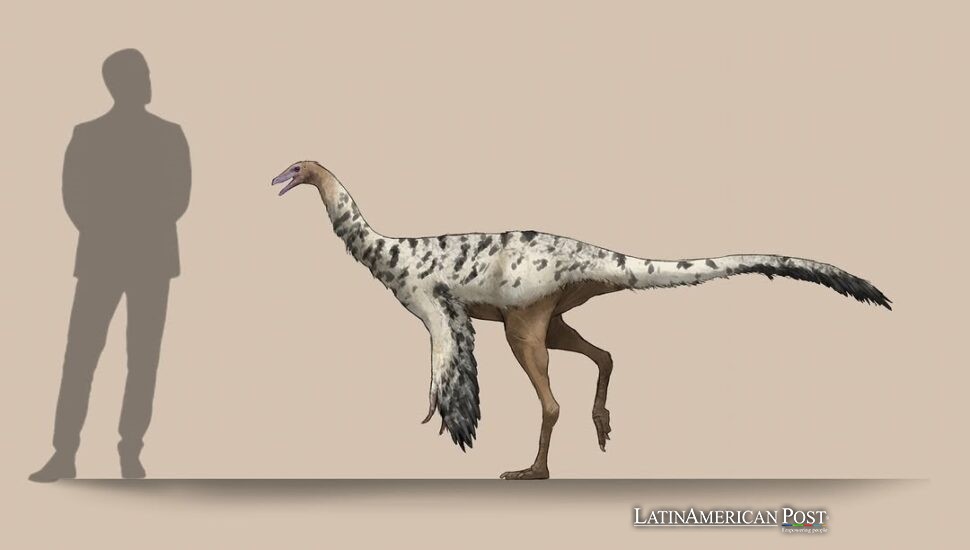

Mexico has emerged as a hotbed for unexpected dinosaur discoveries. The most recent addition to the roster is Mexidracon longimanus, dubbed by researchers as the “long-handed Mexican dragon.” It belongs to the ornithomimid or “ostrich-mimic” group, a clan of theropods famed for toothless beaks and slender, fast-running forms. The partial remains, consisting of limbs, vertebrae, and pelvis sections, have been unstudied since 2014 when they were first unearthed in the Campanian-aged sediment of Coahuila state.

The first clue that Mexidracon wasn’t just another ostrich mimic? It’s unbelievably elongated metacarpals. The dinosaur’s slim palm bones made its hands exceed the length of its upper arms, which points to unique ways it found food. The forelimbs resembled present-day tree sloths, leading scientists to think it used such extended arms to collect plants for eating. Alternatively, some propose that this dino’s multi-jointed grasp might have been perfect for fishing in muddy waters, a scenario that fits the sedimentary environment brimming with oysters and other marine fauna.

Paleo-enthusiasts know that most of Mexico’s dinosaur finds date only to the 21st century. Every new Coahuila fossil stuns the scientific community with clues about how these creatures thrived along ancient coastlines. The roster includes horned ceratopsians, duck-billed hadrosaurs, and imposing tyrannosaurs. Each new genus emphasizes that the region’s Late Cretaceous habitats produced specialized lineages distinct from their northern counterparts in the U.S. or Canada. Such differences could point to partial geographic isolation that led to separate evolutionary paths.

The surface details also support the idea that Coahuila had pockets of rich biodiversity, possibly including wetlands or estuary-like ecosystems. That might explain why Mexidracon bones come from strata associated with watery deposits. If it inhabited marshy edges, those long arms may have assisted in rummaging through reeds or capturing small aquatic prey. Fragments from the same site reveal an environment dense with shellfish—an indicator that these dinosaurs likely contended with brackish shallows and migrating fish.

Odd And Extinct: Ornithomimid Lore

Ornithomimids—literally “bird mimics”—constitute a family of lightly built, bipedal dinosaurs with ostrich-like proportions, minus the feathers. Fossil impressions from Canada confirm that many sported a feathery coat, though whether that extended to flamboyant plumage remains unclear. Typically, these creatures possessed toothless beaks and were reputedly omnivorous, feeding on everything from leaves to small invertebrates. Unlike T. rex or raptors, they would not have been top predators. Instead, they roamed the land for fruit, seeds, insects, or maybe smaller reptiles, employing agility and speed to elude carnivores.

But “Mexidracon longimanus” sets itself apart with its uncommonly proportioned arms. The name “longimanus,” meaning “long-handed,” is apt, given that the palm alone outmatches the entire upper arm in length. Similar but less exaggerated builds in other ornithomimids prompted evolutionary debates: Did they rummage in trees or drag branches down to munch leaves? Could they have had a partial wading lifestyle, snapping up small fish? Despite theories, paleontologists seldom find direct evidence of feeding from fossilized intestines or last meals. Claws can hold clues: If robust or hooked, they might have aided in gleaning fruits or hooking small creatures.

To complicate matters, some have compared these elongated limbs to the arms of modern-day sloths—an apt analogy if the dinosaur’s joints and claws were adapted for snagging overhead vegetation or water prey. This radical shape diverges from the simpler designs in older or more typical “ostrich mimics,” suggesting unique ecological roles in the watery environment. Paleontologists think specialized foraging might have made Mexidracon a partial outlier among its broader group.

Seventy-Three Million Years Ago: Coahuila’s Cretaceous Scene

Geologically, the strata that entombed Mexidracon date to around 73 million years old, firmly placing it in the Campanian stage of the Late Cretaceous. At that time, vast shallow seas covered North America, leaving silt and sandy deposits brimming with marine creatures. Coahuila’s fossil trove, primarily discovered in the last two decades, has yielded an impressive variety of dinosaurs. These finds might eventually rival those in U.S. or Canadian badlands, rewriting the typical narrative that big, showy dinosaur species only roamed further north.

The presence of big hadrosaurs in Coahuila, plus local tyrannosaurids, suggests robust ecosystems, complete with migratory herbivores and apex predators. That Mexidracon thrived in watery margins is unsurprising, given how many dinosaur bones in Mexico are in brackish or nearshore contexts. The environment also explains the shell accumulations, leading to speculation that Mexidracon scavenged from tidepools or devoured tiny marine organisms on the muddy banks.

Such adaptability speaks volumes about how these creatures lived. They weren’t solely farmland roamers or pure forest dwellers: They were opportunists, taking advantage of coastal edges to feed on aquatic or semi-aquatic resources. That’s a far cry from how we often imagine “ostrich mimic” dinosaurs as land-lubbers. If more skeletons of this species or similar forms come to light, paleontologists can refine theories about how they hunted or gathered food.

Future Of Mexican Dino Discoveries

Despite the limited remains documented—part of a forelimb, some vertebrae, limb bones, and pelvis fragments—Mexidracon provides a tantalizing puzzle piece for Mexico’s dino mosaic. Because so many newly revealed species have turned up in the same general window, experts expect a steady flow of additional fossils, each unveiling further local peculiarities or expansions of known lineages. Over time, Mexico’s record might match (or exceed) that of the southwestern U.S. or Canada’s famed fossil hotspots.

In parallel, morphological oddities like enormous metacarpals invite more profound evolutionary questions. Why are these elongated arms in a group typically known for quickness and minimal weaponry? Did the dinosaur face competition from other herbivores, prompting it to exploit resources in the treetops or shallow waters? Or was it a specialized fisher? Paleo-art and speculation are sure to flourish. Imaginative reconstructions already feature a small, lithe dinosaur wading in an estuary, arms extended like multi-pronged spears to snatch unsuspecting fish—be it romantic or purely hypothetical- underscores how morphological adaptation shapes survival strategies.

Beyond Mexidracon, the region’s trove includes some horned dinosaurs akin to Triceratops, crested hadrosaurs resembling the likes of Parasaurolophus, and fearsome predatory lineages, plus distinctly local forms that never ventured north. Each discovery cements the notion of a partial “Mexican province” in Late Cretaceous times, cut off enough from northern neighbors to evolve distinct species. That perspective redefines how we see North American dinosaur biogeography.

Looking ahead, paleontologists hope for more complete skeletons or, ideally, a well-preserved skull for Mexidracon. A more finished blueprint might confirm if its muzzle shape or crest variation (if any) influenced its feeding. Detailed forelimb analysis could confirm if slender digits ended in hook-like claws or more generalized “catch-all” ones. The impetus rests on local field teams: Each year, advanced mapping, high-resolution imaging, and improved excavation methods uncover once-hidden remains in the region’s chalky rock layers.

As Mexico’s scientific framework for dinosaur research expands, museums can better display local paleobiology, inspiring new generations of students. Once overshadowed by the southwestern U.S. dinosaur strongholds, Mexico is forging its identity as a cradle of improbable and specialized species. By bridging cultural heritage with academic inquiry, local communities near Coahuila may also embrace the potential of tourism. If the “Mexican dragon” stirs enough curiosity, it might become a local icon, spurring further hunts for the next big find.

While “Mexidracon” evokes dramatic imagery of a scaly beast, it’s grounded in credible scientific data. Those who imagine flamboyant sails or spines might be disappointed; the real appeal is the dinosaur’s improbable arms. Yet the richly varied environment it inhabited and the abiding puzzle of how it used those limbs keep the find in the public eye. Combined with Mexico’s rising star in paleontology, the “long-handed Mexican dragon” seems set to fascinate dinosaur enthusiasts and casual observers for years to come.

Also Read: Mexico Embraces Future with Ambitious Olinia Electric Minivehicle Production Plan

Ultimately, Mexidracon helps bridge a gap: modern knowledge about large, fast-living ostrich mimics in North America rarely touched on the possibility of watery habitats, specialized arms, or little-known southern lineages. By unveiling what might be a genuinely one-of-a-kind adaptation, Mexico reminds us that dinosaur evolution is more complex and varied than previous narratives suggested. At 73 million years old, the “long-handed Mexican dragon” reaffirms that entire corners of dinosaur history lie waiting in the rocky countryside—and that each surprising clue can broaden our horizons about life in Earth’s distant past.