From Olympic Snowboard Dreams To Cartel Kingpin Between Mexico and Colombia

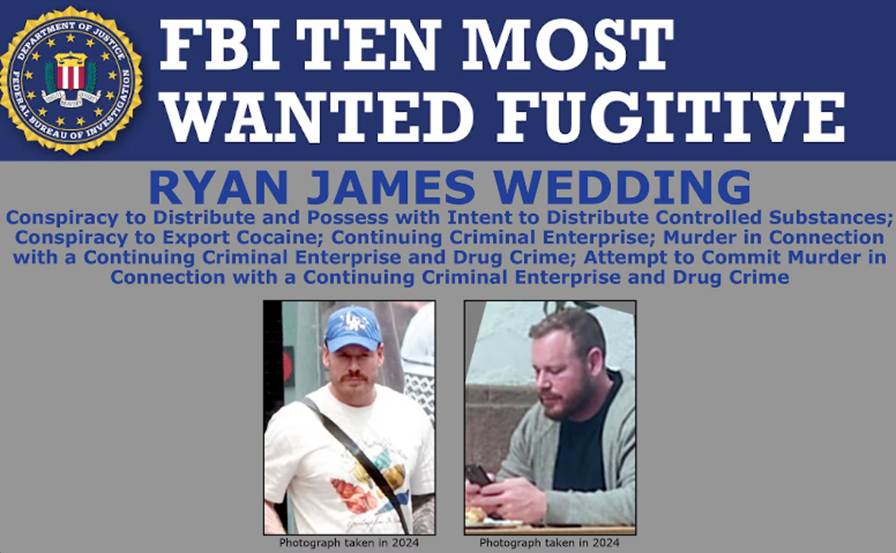

Investigators compare Ryan Wedding to notorious figures like Pablo Escobar and El Chapo, highlighting the scale and brutality of his operations to underscore the grave threat he poses.

An Olympic Dream That Crashed In Salt Lake City

There was a time when Ryan Wedding’s name belonged on the sports pages, not on the FBI’s “Ten Most Wanted” list. Born in 1981 in Thunder Bay, a tough, quiet city in northern Ontario, he grew up in a family built around snow and mountains. His grandparents ran a modest ski hill; his father, an engineer, had been a university skier. Athleticism came naturally, and Canada’s winter-sport machine quickly took notice.

By his early twenties, Wedding had turned to snowboarding, riding the wave of a sport that promised glamour and Olympic glory. He made the Canadian team for the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City, Utah, arriving as a young rider with everything in front of him. But on his first day of competition, a small mistake — the kind that decides medals in seconds — cost him dearly. He crashed out of contention and never recovered from the psychological blow. The dream that had structured his entire youth suddenly evaporated.

Back home in Vancouver, he enrolled at university and poured himself into the gym, chasing the adrenaline rush that competition once brought. He took work as a nightclub bouncer, guarding doors at venues frequented by members of organized crime. It was there, investigators later told EFE, that the line between failed Olympian and aspiring gangster began to blur.

From Cannabis Grower To Prison-Trained Trafficker

The first step was not cocaine but cannabis. In Vancouver’s fertile underground, Wedding set up a large-scale marijuana operation and built a profitable business supplying product to the United States. To move it across the border, he leaned on established outlaw groups, including the Hells Angels, who could offer protection and trucking networks.

By 2008, Wedding aimed to escalate his criminal career beyond marijuana, attempting to move twenty-four kilograms of cocaine from San Diego to Canada, marking a significant step in his rise within the narco hierarchy before a sting ended his plans and led to his arrest.

In 2010, a U.S. court sentenced him to forty-eight months in a Texas federal prison. Before trial, he had already spent seventeen months in a San Diego detention center, long enough to begin mapping out a new life in his head. What should have been a deterrent became something else entirely. An FBI agent later told Toronto Life, in comments relayed by EFE, that prison became a kind of graduate school for the Canadian. “We knew we were giving Wedding all the contacts he needed to go back to a criminal life,” agent Brett Kalina said. “But there was nothing we could do.”

By the time he was extradited to Canada in 2011, Wedding had a clear objective: to control the flow of cocaine and other drugs into his home country using the muscle and supply of Mexico’s Sinaloa cartel.

Mexico As a Safe Haven, Colombia As a Killing Ground

Wedding’s ambitions were as big as his frame — at six-foot-four, he stands out in any room. Authorities say he began organizing shipments of Sinaloa cocaine along Canada’s eastern seaboard, aiming to bring in tons of product each year. But before the first large load could arrive, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police disrupted the route.

Facing renewed charges, Wedding disappeared. Investigators say he fled to Mexico, where he allegedly deepened his ties with Sinaloa networks and began directing operations from relative safety. It was from there, according to law-enforcement sources quoted by EFE, that he is believed to have ordered the killing of an associate in Montreal in 2018, fearing the man had become a police informant.

From his Mexican hideout, ‘El jefe,’ ‘El toro,’ or ‘Public Enemy’ — as he is known — expanded his empire to move around sixty tons of cocaine annually into North America, relying on Canadian truckers capable of hauling up to 350 kilograms per trip across borders and provinces, illustrating the vast scale of his trafficking network.

One key figure in the logistics was Jonathan Acebedo García, a Colombian-Canadian whom Wedding had met years earlier in a Texas prison. Acebedo supervised trucking operations and helped keep the pipelines open between cartel stash houses in Mexico, distribution networks in the United States, and buyers in Canada. The map connecting Mexico and Colombia to North American highways, once drawn by men like Pablo Escobar and Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, now had a Canadian snowboarder at one of its intersections.

When the FBI dismantled part of Wedding’s operation in Los Angeles in the summer of 2024, Acebedo flipped. He turned informant and agreed to testify against his bosses, offering prosecutors a rare insider’s guide to a binational trafficking empire. But on January 31, 2025, just weeks before the trial was due to begin, Acebedo was shot dead in Medellín, Colombia. Investigators say he was murdered on the orders of “El jefe,” likely via Colombian hitmen, in a brutal reminder of how easily the narco war jumps borders.

A Modern Escobar Still Hiding In Mexico

Law enforcement agencies continue their efforts across borders, emphasizing the ongoing challenge to apprehend Wedding and the importance of international cooperation in fighting drug trafficking.

In Washington, senior law enforcement officials from the United States and Canada announced the arrest of several high-ranking members of Wedding’s organization, hailing the operation as a significant blow. But the man at the top remains at large. U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi did not mince words when she announced the charges: Wedding, she said, is a former Canadian Olympian who has become the leader of a transnational criminal empire.

FBI director Kash Patel went even further, telling reporters that no one should underestimate the scale of the threat. According to remarks cited by EFE, he called Wedding “the modern version of Pablo Escobar” and “the modern version of El Chapo Guzmán” — comparisons that investigators do not make lightly.

Now forty-four, the onetime Olympic hopeful is believed to be hiding somewhere in Mexico, under increasing pressure but still protected by the Sinaloa cartel. His rise — from Thunder Bay ski hills to a Mexican refuge, from Olympic halfpipes to cocaine superhighways running through Mexico and Colombia — reads like a Hollywood script. It is also a reminder that the drug trade’s newest protagonists do not always come from Medellín or Sinaloa. Sometimes they start on snow-covered slopes, chasing glory, before discovering that a different kind of adrenaline rush awaits in the shadows.

Also Read: Curaçao’s Caribbean World Cup Miracle Stuns Football’s Giants