Sports

-

SPORTS

Eduardo Nájera’s Homecoming: How a Viking’s Son Is Rewriting Mexico’s Basketball Future

The man who once elbowed his way through NBA paint now walks more slowly—two hip surgeries will do that—but his…

Read More » -

SPORTS

Sports Betting Surges As Latin America Captivates Wall Street's Attention

The sports betting market changes fast, and Wall Street now investigates Latin America's expanding betting sector. At home, the U.S.…

Read More » -

SPORTS

Efraín Juárez Triumphs with Colombia’s Atlético Nacional and Sets Bold Ambitions

In only four quick months, Efraín Juárez changed Colombian Atlético Nacional from a doubtful project into a two-time winner ‒…

Read More » -

SPORTS

South American Soccer Stars Who Dominated Global Stage in 2024

In 2024, soccer stars from South America dazzled with their skills ‒ taking over Europe's top leagues and big international…

Read More » -

SPORTS

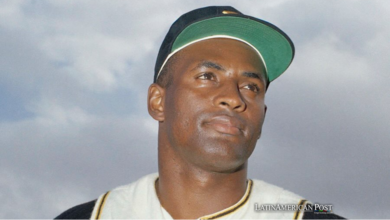

U.S. Honors Puerto Rican Roberto Clemente with Commemorative Coin

Roberto Clemente's legacy shows unmatched accomplishments, kindness, and a strong dedication to fairness. A new U.S. Treasury coin remembers his…

Read More » -

SPORTS

Mexico’s Israel Vázquez: A Fighter’s Legacy of Grit and Greatness

The boxing world mourns the loss of Israel "El Magnífico" Vázquez. Vázquez was a former world champion. Many remember him…

Read More » -

SPORTS

Corruption and the Decline of Colombia’s Olympic Dreams

Latin American sports inspire pride, but scandals also often occur in this region. Colombia's Olympic performance has sharply dropped since…

Read More » -

BUSINESS AND FINANCE

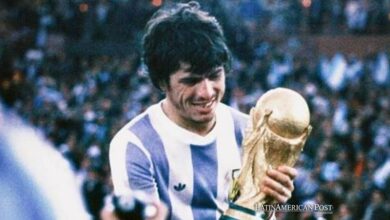

Argentina’s Soccer Controversy: Business Over Sport at Deportivo Riestra

Argentina's Deportivo Riestra stirred outrage by fielding YouTube star Ivan "Spreen" Buhajeruk as a striker in a top-league match against…

Read More » -

SPORTS

Brazil’s MMA Legacy: A Global Force in Combat Sports

Brazilian fighters have long been the backbone of mixed martial arts, bringing an unmatched skill set, toughness, and influence. From…

Read More »