Colombia’s Underwater Graveyard: Divers, Spirits, and the Relentless Search for the Disappeared

For two decades, Buenaventura’s San Antonio estuary has whispered rumors of hundreds of bodies being dumped into its murky waters. Now, a rare alliance of divers, priests, and shellfish gatherers is trying to find the bodies and unearth the truth—before it slips away forever.

A River That Still Holds the War

To most of the world, Buenaventura is Colombia’s busiest port, a hive of shipping cranes and humming containers that move seventy percent of the country’s maritime trade. But just behind that polished exterior lies a haunted silence. The San Antonio estuary, its slow current coiling through mangroves and mudflats, has long carried a reputation far darker than oil spills or discarded nets. To locals, it’s “the other city”—a submerged cemetery where paramilitary death squads once dumped their victims in oil drums, chains, or shallow graves, all swept under by tide and time.

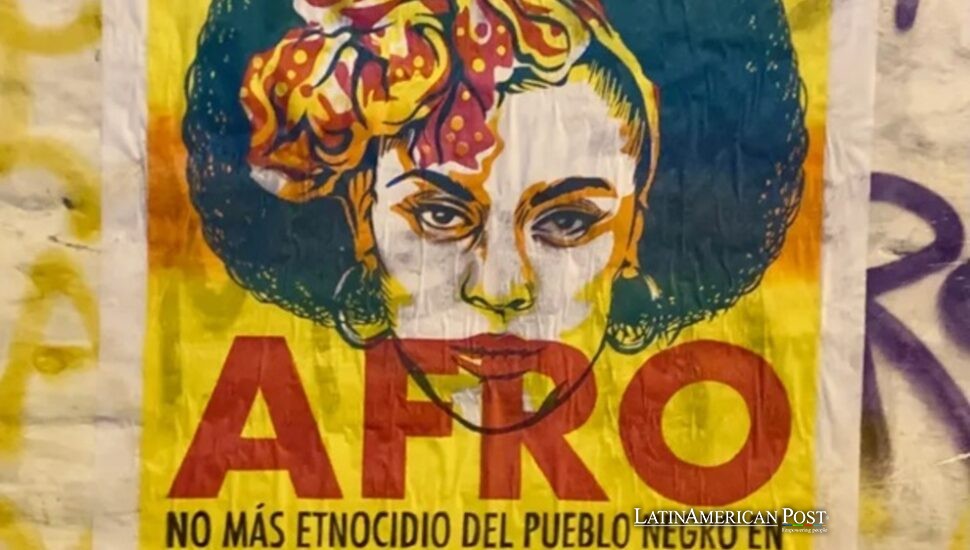

Between 1989 and 2016, these waterways were a war zone in disguise, ruled by armed groups locked in blood feuds and cocaine logistics. According to Colombia’s Search Unit for Persons Reported Missing (UBPD), at least 940 people disappeared in and around Buenaventura. Human rights groups place that figure above 1,300. For years, fear muzzled survivors. Families whispered names but filed no reports. They knew what happened. The river took them. The tide didn’t bring them back.

Only in late 2024 did the government attempt something extraordinary: a seventeen-day, state-backed dive into the estuary itself. “Silence became another tide,” said UBPD coordinator María Victoria Rodríguez, explaining why they chose to search now—knowing full well they might return with nothing.

Beneath the Mangroves, Science and Spirit Collide

Forensic diver Pedro Albarracín did not descend alone.

Before each dive, Yoruba priests traced sacred chalk symbols across his wetsuit, calling on Yemayá, goddess of the seas, and Oshun, goddess of rivers. Their blessing, he said, was “courage when light disappears.” And light did vanish fast. The estuary’s waters are so polluted that visibility often drops to less than a meter. Beneath the surface, Albarracín and a navy diver moved unthinkingly, their fingers combing the sediment near “Skull Island,” a mangrove outcropping long whispered to hide the dead.

Ten sonar-mapped “points of interest” guided the team, but it was the piangüeras—Afro-Colombian women who harvest shellfish barefoot—who truly led the search. Their deep knowledge of mudflat tides replaced the need for GPS. Their hands felt for clues where metal detectors failed. On shore, a second ceremony unfolded: shrines, photographs, candle flames flickering under ceiling fans. Elders listened for omens in the calls of birds and the wind. As anthropologist Adriel Ruiz put it, “Disappearance is not just physical—it breaks the spirit. Looking for bones begins the healing.”

Some divers wore string bracelets, gifts from the priests, said to guard them from the angry souls they might disturb. Albarracín kept his wrapped around his oxygen gauge.

A Search That Finds No Bodies but Awakens a City

In the end, the team surfaced empty-handed.

No skulls. No chains. No IDs or teeth. The estuary, poisoned by sewage, dredging, and industrial runoff, had become what one diver called a “liquid eraser.” Metal drums likely burst long ago. Bones, if they exist, have slipped into deep silt or chemical oblivion.

And yet, for Rodríguez, that wasn’t failure. “Each sweep maps what’s not there,” she said. “And every search shapes the next.”

The UBPD has recovered 2,490 bodies nationwide since 2018, with 1,239 found in 2024 alone. But none from Buenaventura—not yet. That void weighs heavily. Albarracín described climbing back onto the boat, exhausted, only to face mothers on the dock asking, “Did you find my son?” All he could do was shake his head.

Future dives depend on Colombia’s Special Jurisdiction for Peace, where ex-combatants may confess burial sites. New techniques, such as environmental DNA sampling—filtering water for genetic traces—are being tested. Until then, the search pauses, but the ripples remain. During the mission, over a dozen families filed their first-ever reports of disappearance. Local radio now airs live call-ins. Children who once feared speaking their names now write them in notebooks.

PBIColombia

When Memory Surfaces Without Bones

On school trips, children glimpse Skull Island from the road and hear stories of a city inside the water. Trauma bleeds into the everyday: Colombia’s highest rates of PTSD and domestic violence trace back here, to this estuary where the dead never come home.

Local leader Sergio Cubillos helped rebuild his village’s water system after pollutants contaminated the water source upstream. But before pipes, he says, comes justice. At a final Yoruba ceremony, elders asked the estuary to forgive the living for disturbing it—and to forgive itself for becoming a grave.

“We can’t talk about future tourism, investment, or anything else,” Cubillos said, “until we name those the river swallowed.”

Colombia’s 2016 peace accord promised truth, not just peace. But violence still simmers. Disappearances continue. Only reckoning deters repetition, UBPD officials argue. And perhaps this dive—unsuccessful on paper—did just that.

It showed perpetrators that the water is no longer silent. It taught children that ghosts cannot erase their names. It gave mothers, for the first time in twenty years, someone to ask where their sons had gone.

As Albarracín packs for a new mission—this time in Caquetá, where guerrillas supposedly sank cement-filled canoes—he tucks the Yoruba sash back into his bag. “The goddesses come with me,” he says, “because every Colombian river holds secrets. And courage travels better with blessing.”

Also Read: Ecuador’s ‘El León’ Lands in New York, but His Narco Empire Still Roars at Home

Credits: Based on original reporting by The Guardian, with interviews and field research by María Victoria Rodríguez, Pedro Albarracín, Adriel Ruiz, and local community leaders. Research supported by Colombia’s UBPD, the Special Jurisdiction for Peace, and partner organizations in Buenaventura.