Argentina Publishes Nazi Files Prompting Stark Historical Reflections

Argentina’s government put declassified documents concerning Nazi activities on a public website. The papers reveal decades-old intelligence about people such as Adolf Eichmann plus Josef Mengele. The action caused a new examination of the country’s past during wartime and secret diplomatic agreements.

Opening the Files to the Public

In an announcement on Monday, the administration of President Javier Milei revealed that Argentina’s National Archives had uploaded nearly 1,850 records and 1,300 decrees—once top-secret—concerning the arrival and conduct of Nazi figures after World War II. According to an official statement seen by EFE, these materials, declassified in 1992 but previously accessible only by in-person request, now appear online for unrestricted viewing.

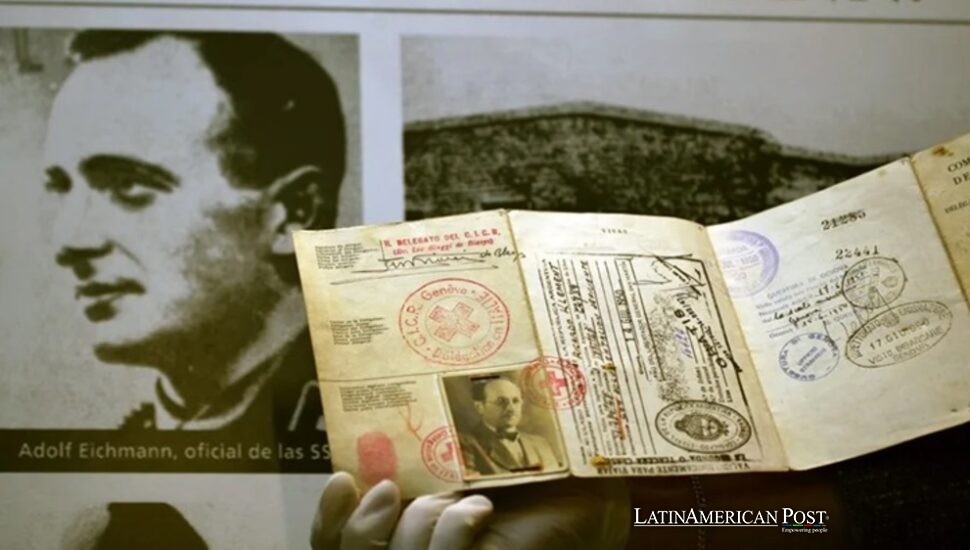

Among the highlights are references to notorious Nazi officials such as Adolf Eichmann and Josef Mengele. Researchers have long known that these men found sanctuary in Argentina during the mid-20th century, yet details of their daily whereabouts and the local networks that aided them remained fuzzy. The newly disclosed files include intelligence reports from the Federal Police’s Foreign Affairs unit, the State Intelligence Secretariat (SIDE), and the Gendarmerie—collected between the 1950s and 1980s.

Officials say the project reflects broader attempts to illuminate Argentina’s post-war entanglements, an era when the country quietly became a haven for fugitive Nazis. “We’re not rewriting history,” one Milei government insider explained to EFE. “But letting citizens see these documents fosters accountability and encourages deeper historical research.”

Revealing the Nazi Trail

For many years people discussed how important Nazis entered Argentina. Talk in the area mentioned hidden organizations. People from Argentina or Germany who lived in another country created paths across the Atlantic. Historians assert that President Juan Domingo Perón’s administration tolerated or even facilitated some arrivals, seeking strategic benefits or simply turning a blind eye amid post-war upheaval.

Researchers highlight the significance of these newly scanned intelligence dossiers: they detail police surveillance on Eichmann and other ex-officers, charting their relocation from European port cities to small Argentine towns. Some documents note coded telegrams from Berlin-based contacts, while others record local authorities’ confusion or complacency. Men like Eichmann reportedly lived under assumed identities, taking modest factory jobs and blending into unsuspecting neighborhoods. Though Eichmann was eventually captured in 1960 and spirited to Israel for trial, critics remain curious about the official knowledge that preceded his arrest.

Argentine historian Julieta Llerena, who has studied Jewish immigration in Buenos Aires, told EFE that these archival files could reshape understandings of the state’s role. “We’ve always suspected mid-level bureaucrats, if not top-level figures, condoned the presence of such criminals,” Llerena said. “Now we might have the missing links, confirming how far the lines of complicity reached, or whether bureaucratic inertia was partly to blame.”

Searching for Transparency

In addition to the Nazi-related material, the government disclosed a trove of about 1,300 once-classified presidential decrees. Dating from 1957 to 2005, they reveal clandestine foreign policy choices, internal security measures, and other delicate matters. Some were initially declassified in 2012 by then-president Cristina Fernández, but only now do they appear in digitized form for public viewing.

“This is more than rummaging through dusty files,” said a spokesperson from Argentina’s Vice Cabinet Office. “We see it as an act of institutional openness—pulling back curtains on a hidden chapter of national governance.” Observers say the release aligns with a broader trend: over the past decade, Argentina has embraced measures aimed at reckoning with its political past, including trials for dictatorial-era crimes and the partial unveiling of secret intelligence documents.

Still, the question arises: how will everyday Argentines respond? While some historians and genealogists greet the disclosure with excitement, ordinary citizens may feel unsettled or indifferent. The official told EFE that “any robust democracy demands confronting its skeletons,” yet others warn of a swirl of misinformation that can arise when raw intelligence notes appear online absent context. “We need historians guiding these revelations,” Llerena stressed, adding that “reading spy files can be murky.”

Nevertheless, organizations like the Simon Wiesenthal Center, which investigates Nazi-era atrocities, applaud the digitalization. They had received earlier versions of the data but noted that easy online access could spur cross-border investigations. “We can piece together more consistent timelines,” one center representative said. “Modern technology helps unify scattered fragments of knowledge.”

Behind these public disclosures lies a deeper mission: to ensure that historical accountability outlives political agendas. Many recall how Eichmann’s abduction from Buenos Aires in 1960 triggered diplomatic friction between Argentina and Israel. Now, six decades later, the newly revealed records may shed fresh light on how intelligence agents tracked or lost track of Eichmann’s presence. Additionally, some might clarify the rumored sightings of Mengele, the infamous camp physician.

As the country sifts through these bombshell documents, the conversation extends beyond any single figure. Critics wonder if more is forthcoming: might the government unseal further materials linked to the so-called “rat lines,” the clandestine routes used by Nazis to slip into South America, or detail the fate of smaller, less-famous collaborators? For the moment, the Milei administration’s stance indicates a willingness to open the vault fully.

Critics wonder if the action attempts to divert attention from money problems or troubles at home. Government workers deny this idea. They say the release belongs to a “strategy for transparency over time.” Historians promise to study each page. They expect detailed research. Archivists will separate believable information from conspiracy stories.

Also Read: Colombia Pioneers Safe Heroin Injection Transforming Latin American Reality

For the population of Argentina, digital publishing of records related to the Nazi time is important. It allows young citizens, perhaps unaware of Argentina’s complex ties following the war, to understand problems of neutrality, involvement, or tacit approval that shaped earlier incidents. Documents reveal a valuable insight: A community progresses with honesty despite the discomfort and transitions from secrecy to scrutiny.