Argentina’s Dictatorship Document Declassification Sparks Controversy as Echoes Persist

In a country still grappling with the aftermath of a dark chapter, Argentina’s newly elected government has triggered fierce debate. By unveiling plans to declassify military-era documents while casting doubt on the number of disappeared citizens, it challenges entrenched memories.

Milei’s Controversial Announcement

Argentine President Javier Milei’s administration announced it would declassify all military documents related to the country’s last dictatorship (1976–1983). The unexpected move was accompanied by an institutional video disputing the widely cited figure of 30,000 desaparecidos (disappeared persons), a number maintained for decades by human rights organizations. The government says that this number is too high. It calls the figure a made-up claim tied to efforts to gain help from other countries in the 1970s and 1980s. Many people see it as a change in the known facts.

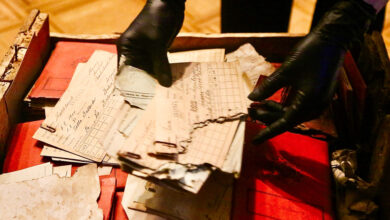

In a press conference at the Casa Rosada, the seat of the Argentine executive, presidential spokesperson Manuel Adorni confirmed that all files under the custody of various state intelligence agencies—including the powerful Secretaría de Inteligencia de Estado (SIDE)—would be transferred to the Archivo General de la Nación. This agency oversees the preservation of historically significant documents, making them available for public scrutiny. According to Adorni, the decision upholds an unfulfilled 2010 decree by former President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner that mandated the release of classified material from the dictatorship era. In theory, exposing the documents should help find facts and clarify what took place during one of Argentina’s most violent times.

Problems emerged right away because of the government’s view on the dictatorship’s death count. Milei’s group says the official figure of 30,000 missing remains unproven at best or a false adjustment meant to shape local as well as global views at worst.

These words cause conflicts in a society that still handles pain from the “Dirty War,” when many people were tortured, locked up, or killed without a proper trial. For survivors, victims, relatives, or campaigners, challenging these figures means rejecting the many human rights abuses of that period. Opponents called for full probes, clear treatment of released files, plus a promise to care for the memory of the lost.

The 1978 World Cup: Exciting Games Amid Turmoil

One of the era’s starkest ironies is that, at the height of the dictatorship, Argentina hosted the 1978 FIFA World Cup. The tournament gave the military government a global stage to display an image of national pride and unity. Spectators around the world saw exciting soccer games, especially when the host nation won the final. A few miles from the cheering fans, secret prison sites ran without supervision. This clear difference turned the 1978 World Cup into a strong sign of national joy plus state-sponsored fear.

Despite the win on the field, human rights groups said that soccer served as a tool for politicians to cover up a growing crisis. People who spoke out or defied the state’s plans were forced into silence. While fans celebrated Argentina’s strong show and the raising of the trophy, many citizens were arrested, tortured, or lost. Over the years, the hard truth behind those matches came to light. Many players themselves only discovered the true extent of the violence after retiring, expressing regret that their sporting glory was manipulated to legitimize the dictatorship.

Sports historians and human rights advocates stress the need to admit this contrast: praising Argentina’s soccer win while also recalling terrible acts that took place at the same time. The demand for clear government records gains extra weight with these World Cup memories since the dictatorship staged a large event to hide crimes done in secret. If the current government lifts restrictions on official records, it might offer a fuller account of how the regime used international events to boost its image while domestic repression grew more severe.

Human Rights and the Ongoing Fight for Truth

The debate about the declassification work goes beyond counting the missing. Activists fear the government’s edits may weaken old legal claims, reduce the trust in survivor statements, and take away the strength of those claims. After Argentina became democratic in 1983, many courts tried those responsible for human crimes; several ex-military commanders were convicted. Groups like the Mothers and Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo worked hard to win fairness, reunite families with taken children, and bring answers. Their decades-long struggle stands in stark contrast to the administration’s recent statements.

Meanwhile, high-profile figures like the right-wing writer Agustín Laje—head of the think tank created by Milei—use the newly released video to push narratives suggesting Argentina has fallen victim to what they call “the theory of a single demon.” According to Laje, the dictatorship’s violent crackdown emerged from the turbulent climate of the Cold War, a period in which various guerrilla groups also resorted to armed conflict. This viewpoint complicates the broader public discourse by implying that only one side of the story—centered on the brutality of the military—has been highlighted while minimizing state responsibility or shifting the focus to the violence of guerrilla factions.

After Milei took office on December 10, 2023, worry came over less money for national memory sites as well as the firing of key workers at human rights offices. These moves boost fear that the government plans to change history to fit a strict or revised view. Many people met on Argentina’s National Day of Memory for Truth and Justice to demand clear answers plus responsibility. They claim that the darkest chapters in history should not be hidden in archives but be reviewed fully to keep collective memory alive.

As the archives move under the purview of the Archivo General de la Nación, the integrity of their contents and the transparency of the process become critical. Will the release of these records contribute to healing, or will it fuel political agendas seeking to rewrite the past? For many Argentines, the answer to that question shapes not only how they interpret the dictatorship era but also the very essence of national identity. In a country where football victories can rally proud public and historical wounds remain raw, the Milei government’s bold act of declassification—and its simultaneous rejection of a longstanding estimate of disappeared citizens—triggers a nationwide reflection: Is Argentina ready to confront the full weight of its history, or will this turn into another chapter of political power plays and polarizing rhetoric?

Also Read: Venezuelan Families Confront US-Salvadoran Prison Transfer Silence

The fight over how to remember the missing versus telling different stories shows that Argentina’s road to peace stays full of problems. Even the joy of the World Cup cannot reduce the need to look at, know, or admit old wrongs. Only time—and the transparent handling of newly opened archives—will determine if this fresh declassification effort emerges as a step toward genuine truth and justice or simply a reshuffling of the historical record in favor of contemporary political aims.