Ecuador votes Sunday for a new president

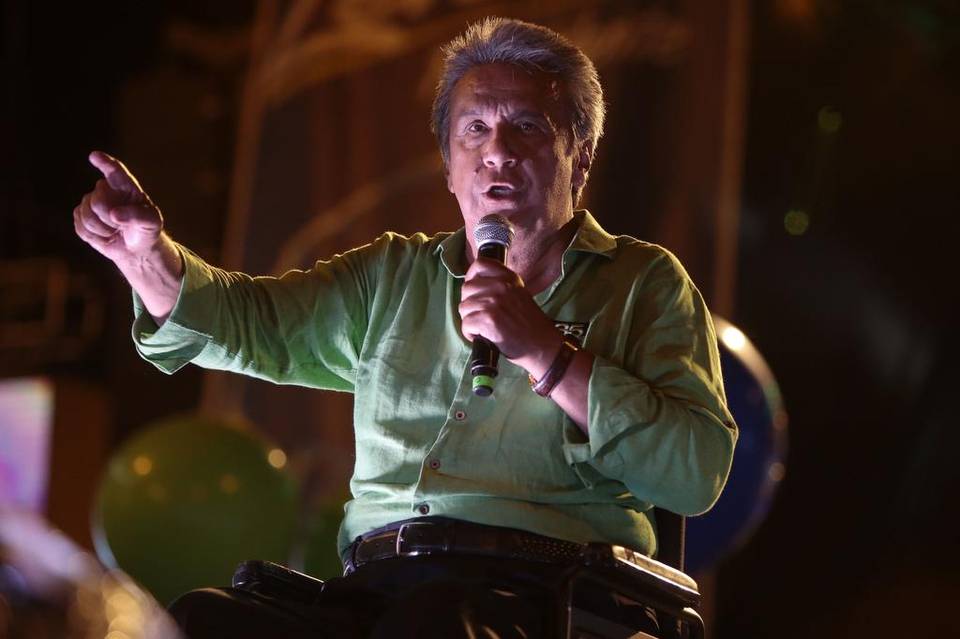

Lenín Moreno, the front-runner in Ecuador’s presidential race, was trying to get through his stump speech on Wednesday when he was repeatedly drowned out by the chant of “Just one round! Just one round!”

The roar from the crowds was both political boast and desperate plea: If Moreno, the ruling-party candidate, can win Sunday’s vote by a wide enough margin, he can avoid a runoff. If he doesn’t clinch it, he’ll have to face a unified opposition in an April 2 vote. And even his most ardent fans worry he’s not up for that fight.

“I look IGNORE INTO the sky every night and pray that he’ll win in the first round,” said Eugenia Flores, a 63-year-old retiree. “If he doesn’t win, they’re all going to gang up on him.”

Campaigning officially ends Thursday, and Moreno and his two closest rivals, former banker Guillermo Lasso and former Congresswoman Cynthia Viteri, are holding their closing rallies in the port city of Guayaquil.

The race in Ecuador is being watched throughout the region. At stake is the legacy of President Rafael Correa and his “Citizens Revolution” — a decade-long national shakeup that led to new roads, schools and hospitals, even as critics say it put the country deep in debt, trampled civil liberties and free speech, and spawned corruption.

Venezuela similarities?

Aside from Bolivia’s Evo Morales, Correa is arguably South America’s last charismatic leftist. And in a region not known for smooth transitions, the questions remains whether or not he can pass the reins to his one-time vice president, Moreno.

The scenario reminds some of Venezuela in 2013 — a comparison that pleases Moreno’s opponents. In their telling, Correa is like the late Hugo Chávez of Venezuela, a charismatic leader who handed off a bankrupt country to a hapless successor, Nicolás Maduro.

Moreno “is widely regarded here as Correa’s Nicolás Maduro,” Lasso told Teleamazonas television on Thursday. “He has no leadership and no personality of his own.”

And in recent weeks, Moreno and his Alianza País party seem to have been ripping more pages from the Venezuelan playbook: vowing to give away tens of thousands of free and subsidized homes, boost monthly social security payments and offer no-collateral small business loans.

How the cash-strapped government will pay for it all remains unknown.

But comparisons with Maduro don’t always hold up.

Moreno, 63, has political capital of his own. A onetime businessman who has been paraplegic since a botched robbery in 1998, Moreno was Correa’s vice president from 2007 to 2013, and he used the position to be an advocate for the disabled. Many in Ecuador credit him for helping make the country more inclusive and accepting.

“This is the time to create a more luminous future,” he told thousands of cheering and banner-waving supporters at a rally in Quito. “Because that’s what revolution is: moving forward and never retreating.”

But some worry about Moreno’s ability to lead the march. When he stepped down as vice president three years ago, he cited health reasons. And he’s often talked about being in chronic pain because of his injury. Those fears are casting the spotlight on his running mate Jorge Glas, who is Correa’s current vice president.

A lingering scandal at state-run Petroecuador oil company has implicated more than a half dozen officials, including one who has pointed the finger at Glas. In addition, representatives of the Brazilian construction firm Odebrecht pleaded guilty in U.S. courts to paying millions of dollars in bribes for contracts in almost a dozen countries, including $33.5 million in Ecuador. But officials here have yet to name any local suspects.

Glas and Correa have said the allegations are baseless and part of a smear campaign.

Questions of corruption

While corruption ranks high amid people’s worries here, it’s not clear how much the allegations might matter at the polls.

“The issue of corruption has exploded in the middle class, but it’s not an issue that has resonated among the lower classes,” said Luís Verdesoto, a Quito-based political analyst. “The government has been able to build a protective fence around that segment and that’s where they have their strongest supporters.”

Data released by the Quito-based firm Cedatos last week, ahead of a polling blackout, found Moreno had 32 percent of the vote versus Lasso’s 21 percent. Former Congresswoman Cynthia Viteri and former Quito Mayor Paco Moncayo had 14 percent and 8 percent, respectively.

But the poll results are also marred by uncertainty, as a full 40 percent said they didn’t know who they would vote for.

Moreno needs to win at least 40 percent of the vote and hold a 10-point lead over his nearest rival to avoid an April 2 runoff. Some analysts say they believe Moreno might be within striking distance of those margins.

On Thursday, the opposition CREO party, which Lasso leads, raised the specter of fraud. In a statement, the party said it had found “serious irregularities” in the voting process. Among the issues, they said they were not allowed audit the computer servers that will be collecting the voting information, and that they found faulty “security stickers” on boxes of ballots.

“This is additional proof that the [National Electoral Council] cannot guarantee the reliability of the electoral process,” the party said.

Even so, Lasso has found a receptive audience in the middle class with promises to reinvigorate the private sector, attract foreign investment and create more than 1 million jobs. He said he’ll pay for public works by eradicating cronyism and corruption. (Ecuador is ranked 120 out of 176 countries in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index.)

But Lasso is also carrying baggage. Many remember him in his role as a member of President Jamil Mahuad’s (1998-2000) economic cabinet. Mahuad was ousted after he dollarized the economy and, in the process, decimated many people’s life savings, even as bankers and the financial elite were perceived as prospering from the wreckage.

José Carrion, a 32-year-old cab driver, said he wasn’t inspired by Moreno but thought he might be the only one who could keep a lid on simmering discontent. From 1996 until Correa took power in 2007, the country burned through eight presidents, ousted by congress and angry mobs.

“I remember what it was like before, with strikes every other week and all sorts of problems,” he said. “I don’t want to go back to that chaos.”

By any yardstick, Correa will be a hard act to follow. Despite his recent troubles, he remains one of Latin America’s most popular leaders. But critics say his popularity was built on the back of deep debt, short-changing social security and selling off the country’s future.

Douglas Coronel, a 38-year-old lawyer, said whoever takes power will have to face the harsh reality of budget cuts and belt tightening.

“The oil bonanza that we had is never coming back,” he said. “We all have to get used to this new reality.”