Bolivia’s Second Chances Are Made of Bread, Metal, and Thread

At three thousand nine hundred meters above sea level, just outside La Paz, a place designed for punishment smells, unexpectedly, like warm bread. In Qalauma, young Bolivians in trouble with the law shape metal, stitch cloth, and carve wood—practicing, quietly, the hard art of returning.

Where the Altiplano Teaches Patience

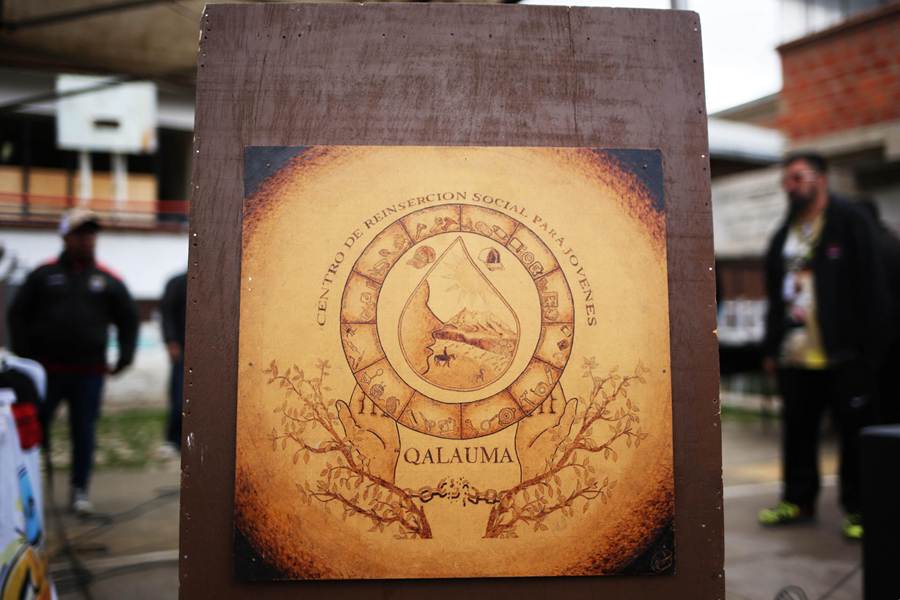

The name is a promise in itself. “Qalauma”, an Aymara phrase often rendered as “the drop that carves the stone,” sits in the Andean municipality of Viacha, roughly thirty kilometers from La Paz, on the high, thin air of the Altiplano. The center is run by Bolivia’s Dirección General de Régimen Penitenciario, and it houses young people “in conflict with the law” up to twenty-eight years old—a detail that matters, because it places adolescence, early adulthood, and all their unfinished identities inside a system that can either harden a person or help them re-form.

Inside, the official language of rehabilitation is practical. The workshops are less about inspirational slogans than about the slow, repetitive practice of skills that can become income. Young men learn metalwork, baking, screen printing, leatherwork, agriculture, sewing, and artisan crafts ranging from miniature carvings to furniture. The purpose is not abstract. In a country where job markets can be informal, where a last name or a rumor can bar you from opportunity, a trade is one of the few things you can carry out of a locked gate without anyone’s permission.

That is why the center’s daily rhythm includes production on a scale that surprises visitors who imagine incarceration as pure idleness. “Existe producción de esculturas, artesanías, carpintería, ropa, se hace repostería, se hace pan, unos tres mil panes todos los días, y se hace mucha producción en cuanto a muebles y también tenemos carpas en las cuales tenemos animalitos y hay vegetales también,” said Brayan López, the La Paz departmental director of the penitentiary regime and a police major, describing the mix of crafts, carpentry, clothing, pastries, bread, furniture, and small-scale farming, he told EFE.

It is a description that carries an argument: if the state wants fewer repeat offenses, it has to treat reintegration as a material problem, not a moral lecture. People return to what they know and what they can access. If what they know is only survival under pressure, society should not be surprised when they survive the same way outside.

Miniatures of the Future, Sold in Plain Sight

This week, the center’s patio became a small fairground, a public-facing pause in the daily grind. The young people displayed what they had made—objects that, on a table, can look playful and harmless, but in context become evidence of time spent differently. There were wooden boats, houses, and cars, leather wallets and accessories, and rows of clothing: jackets, coats, and knitted caps. There were metal ornaments, too—one of the most striking being an X-wing, a ship from Star Wars, remade in the language of bolts, cuts, and patient welding. Nearby, practical metalwork took shape in the form of wine-bottle holders and phone stands, a reminder that craftsmanship can be both expressive and utilitarian.

Across other tables, softness dominated: cloth roosters with comic pride, felt figures, keychains in bright familiar shapes. Jack Skellington, the thin-limbed protagonist of Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas, appeared as a small doll—proof that, even within institutional walls, global pop culture continues to seep in, offering people symbols to borrow and remake. So did the red and green mushrooms from Mario Bros, turned into trinkets. There were Spider-Man dolls, Snoopy, cats, mice—an entire miniature world stitched and crocheted in the style of Japanese amigurumi, those small-to-medium yarn figures that ask for steady hands and a willingness to start over when a loop goes wrong.

What makes these displays politically relevant is not the cuteness. It is the way the goods travel into the city’s cultural calendar through Alasita, the Bolivian heritage festival of abundance and miniature wishes that begins on January twenty-four. This is the season when people buy tiny representations of what they hope to gain—money, homes, jobs, passports—then ask for them to be blessed, as if faith can nudge the real world. When the penitentiary system inserts its production into Alasita, it is doing something delicate: asking the public to see incarcerated people not only as cautionary tales but also as workers and makers whose hands can contribute to the economy and culture.

During the event, López announced a broader “Feria de la Productividad” across the penitentiary system in La Paz, including Qalauma, timed to the Alasita season. The goal, he said, is to show how reinsertion is being pursued, while giving people the “tools” to adapt more easily once they are free. “…cuando se encuentren en libertad, puedan adaptarse con mucha más facilidad a la sociedad,” he explained to EFE.

In a region where security debates often reduce people to numbers—arrest counts, prison populations, crime rates—this kind of fairness forces a more complicated conversation. The public is asked to reckon with the idea that rehabilitation is not a soft indulgence but a safety policy: fewer people returning to crime means fewer victims, fewer police resources drained, fewer families broken in two directions at once.

Freestyle, Therapy, and the Meaning of a Name

The fair did not rely only on products. It also held a freestyle competition, giving space to the rhythms of urban art. That choice is not cosmetic. In places like Qalauma, expression can be as necessary as employment, because reintegration is not only economic—it is emotional and social. Young people who have learned to stay guarded, to react fast, to read danger in small gestures, may carry those habits home. Art, even imperfect and improvised, can soften the reflex to harden.

One of the most persuasive voices at the event was not an official’s. It was a young man named Ronald, incarcerated for three years at Qalauma, who spoke about learning pyrography—burning images into wood—and drawing. He described sharing that talent with others, not as a hobby but as a kind of internal medicine: an occupation that becomes therapy, a way to become calmer, less volatile, more capable of living among others without always bracing for impact. “…compartir este talento… para que puedan tener una ocupación para que les pueda servir como terapia y ser personas más tranquilas,” he said, according to EFE.

Then he did something even more ambitious: he invited outsiders to see the place differently. “…que puedan conocer este centro de ‘Qalauma’, que hay jóvenes que tienen mucho talento, que realmente quieren reinsertarse a la sociedad,” Ronald added, expressing his hope to continue pyrography once he regains freedom, he told EFE.

This is where the name “the drop that carves the stone” stops being metaphor and becomes method. A single workshop does not erase structural inequality. A fair does not undo stigma. But repetition matters: day after day, three thousand breads, one carved line at a time, one stitched seam, one verse improvised in a courtyard. That is how people practice becoming employable, yes—but also becoming legible to a society that often prefers simple villains to complex neighbors.

The productivity fairs, officials said, began at the Patacamaya facility in the Altiplano, continue at the Centro de Orientación Femenina de Miraflores in La Paz, and then move to the San Pedro prison in the historic center on January twenty-four, the opening day of Alasita. And in a detail that signals ambition beyond symbolism, López said authorities hope to secure space at El Alto International Airport soon. This gateway serves La Paz, to exhibit and sell products made by people deprived of liberty, he told EFE.

If that happens, it would place these goods—bread, leather, metal, stitched miniatures—where Bolivia meets the world. It would also put the country’s reintegration project under a brighter light: not hidden behind walls, but displayed in the everyday flow of departures and arrivals, like a nation admitting that justice is not only about what you take away, but what you help a person build before you let them go.

Also Read: Bolivia’s Freestyle Behind Bars Program Gives Incarcerated Youth a Second Chance