Mexican Math and Moonlight: How the Maya Coded the Eclipse Clock of the Dresden Codex

For centuries, the Dresden Codex has stared back at us from museum glass like an enigma—its bark-paper pages filled with gods, glyphs, and numbers too precise to be coincidence. Now, two researchers believe they’ve decoded one of its greatest secrets. According to a new analysis, by John Justeson and Justin Lowry titled “The design and reconstructible history of the Mayan eclipse table of the Dresden Codex”, the ancient Maya didn’t just record eclipses—they predicted them, using an intricate lunar-mathematical model that married skywatching with sacred time, precision with poetry.

A Bark-Paper Book and a Sky Full of Numbers

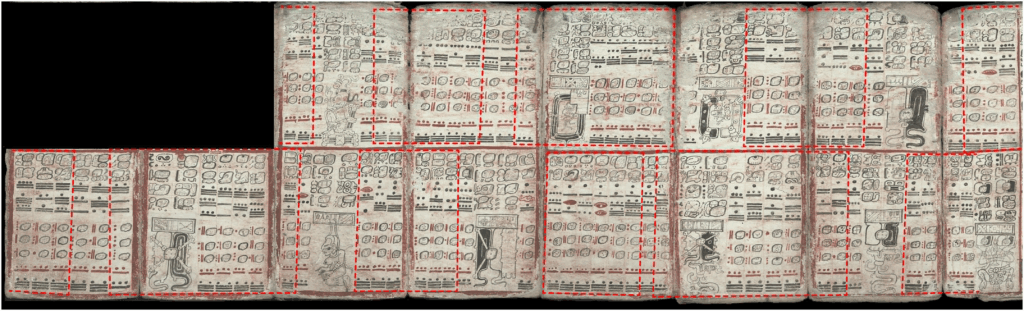

Before telescopes, before equations, there were eyes, rituals, and foldout books of bark. The Dresden Codex—painted more than seven centuries ago in Yucatán—is the most complete surviving Maya manuscript, 39 panels long, unfolding like a cosmic accordion. Within its pages, jaguar gods chase the Sun, serpents coil through glyphs, and rows of numerals pulse like heartbeat notations of the sky.

Hidden among those images, Justeson and Lowry found a 405-month cycle—a pattern of lunar intervals so carefully counted that it forms a predictive engine. Where earlier scholars saw records of past eclipses, the new study sees forecasts, methodically arranged to anticipate where and when the next shadow would fall.

“The Maya built a model,” the authors write—an algorithm in calendar form. It charts 69 new-moon dates spread across 405 synodic months, with corrections that keep the Moon’s rhythm aligned with its nodes—the invisible points where eclipses are born. The record shows how Ajq’ij, or daykeepers, moved through time step by step, counting from each new moon, watching patterns emerge until they could predict darkness itself.

From Lunar Calendar to Eclipse Engine

A solar or lunar eclipse does not occur with every new or full moon. The geometry must be exact—the Moon crossing Earth’s orbital plane at the right moment, at one of two nodal crossings. The Maya noticed this long before orbital mechanics gave it a name. In the Codex, they grouped new moons into eclipse seasons—clusters of six lunations where the alignments reappeared, separated by longer gaps of 11 or 17 months when the sky was clear.

Over 405 months, the Codex shows 55 possible eclipses—most in neat six-part series, one stretching to seven. The pattern repeats with the elegance of a celestial clock, the kind of pattern only visible after centuries of naked-eye observation.

But even the best clocks drift. The Moon’s nodes shift slowly westward, completing a regression every 18.6 years. Left unchecked, that drift would push eclipse seasons out of phase. The Maya didn’t patch the problem by trial and error—they built the correction into the table.

The Overlap Trick That Tamed Celestial Drift

Instead of restarting their 405-month table at the end of a cycle, the Maya overlapped it with the next, beginning a new sequence 223 or 358 months in. Those numbers are not random; they are the harmonic gears that synchronize lunar and nodal time.

The 223-month interval mirrors the modern Saros cycle, the cornerstone of eclipse prediction used today. By overlapping tables at those intervals, the Maya effectively reset the phase drift—snapping the shadow’s path back into alignment.

When the researchers compared the Codex’s projected eclipse seasons with NASA’s modern catalog, the match was uncanny. The manuscript pinpointed windows when eclipses would have been visible not only over Mesoamerica but around the globe. What this meant was extraordinary: without lenses, compasses, or metals, the Maya had produced a planetary model of lunar behavior, built only from arithmetic and faith in observation.

Their math didn’t just describe the heavens—it kept time with them.

Sacred Time, Scientific Timing

Why 405 months? The answer is as philosophical as it is mathematical. The count—11,960 days—corresponds almost precisely to 46 rounds of the 260-day Tzolk’in, the sacred cycle that ordered life and ritual. The Codex’s authors weren’t dividing the sky for curiosity’s sake; they were weaving celestial recurrence into the fabric of destiny.

Earlier scholars, like Floyd Lounsbury, suspected this: that the lunar tables were first a calendar tool, not a simple eclipse log. The new research extends that insight—showing how layers of cycles, overlapped and folded together, transformed a lunar diary into a predictive map. The arithmetic of the heavens became an act of devotion.

A solar eclipse, for the Maya, was not just an event—it was a being. In Nahuatl, it was Tonatiuh qualo, “the Sun is eaten”; in Maya, Pa’al K’in, “the Sun is broken.” It was a wound in time, foretold by the exact numbers that governed marriage days, planting seasons, and royal anniversaries. The daykeepers—astronomers and priests in one—stood at that intersection of science and faith, keeping a watch so steady it still instructs the modern world.

@science.org

When the Past Predicts the Present

Only four Maya codices survived the conquest and burning. Of them, the Dresden Codex remains the most complete and the most mathematical—a bridge between human patience and cosmic recurrence.

The new study by Justeson and Lowry restores the table’s genius. The 405-month cycle, its six-lunation eclipse seasons, and the precision overlaps at 223 or 358—together they form a mechanism of prediction, tested against modern data and found astonishingly accurate.

What’s most humbling is how this discovery reframes the idea of progress. In an age ruled by algorithms, the Maya built theirs from ritual rhythm and skywatching, painted on bark and carried across centuries.

Their eclipse code was not a machine; it was a collaboration between humans and the cosmos. It shows that mathematics can be sacred, that observation can become prophecy, and that even without modern instruments, a civilization could look up at the darkened Sun and say, with quiet certainty—we knew you were coming.

Also Read: Brazil Builds a School Where Influencers Learn Business Before Fame

Based on the study by John Justeson and Justin Lowry, “The design and reconstructible history of the Mayan eclipse table of the Dresden Codex.” Sci. Adv. 11, eadt9039 (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adt9039