Lasso Dissolves the Legislature: Is the Same Thing Happening in Ecuador as in Peru?

The dissolution of the Ecuadorian Assembly by the president, Guillermo Lasso, seems to indicate that the political crisis in Peru is repeated in Ecuador.

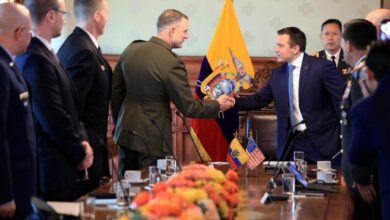

Photo: TW-LassoGuillermo

LatinAmerican Post | Santiago Gómez Hernández

Listen to this article

Leer en español: Lasso disuelve el legislativo: ¿Está pasando en Ecuador lo mismo que en Perú?

Anyone aware of the Latin American political reality will notice the loop of situations that occur in different countries. Less than six months ago, we faced a political crisis in Peru when President Pedro Castillo ordered the dissolution of Congress and, in response, the legislature removed the president. This left the Inca country at severe institutional risk and a social outbreak between followers of former President Castillo and the new government of Dina Boluarte.

Well, history repeats itself in Ecuador. The country located in the middle of the world faces a similar scenario. Several elements are repeated, and many others indicate a complex difference.

Constitutional Act

The Ecuadorian president, Guillermo Lasso, announced that he would activate the "cross death" contemplated in Article 148 of the Constitution. This measure has immediate and subsequent effects. For example, it is ordered to dissolve the National Assembly.

You can also read: The Colorado Party of Paraguay, the Hope of the Latin American Right

This article can only be carried out if the legislature "has assumed functions that do not correspond to it constitutionally, a prior favorable ruling of the Constitutional Court; or if it repeatedly and unjustifiably obstructs the execution of the National Development Plan, or due to serious political crisis and internal commotion."

This measure orders the call for general elections in advance. And while the National Assembly is being installed, the head of state may issue decree-laws (with the prior approval of the judicial body) and which may be repealed by the legislature.

In Peru, Pedro Castillo invoked Article 134 of the Magna Carta. This is only possible if Congress "has censured or denied confidence to two Councils of Ministers." Suppose it is true that the Peruvian president had to face several political trials of his cabinet. In that case, several legal analysts agree that the denial to the entire Council of Ministers was not fulfilled.

Cross Death and Dissolution

Another important difference between both cases, which many want to highlight to demonstrate that in Peru, there was an attempted coup d'état, and in Ecuador, its democratic regime continues, are the consequences of both measures. While Peru's Article 134 orders the dissolution of the Legislative, Ecuador's is for the Assembly and the Presidency. In theory, Lasso also leaves power; only he can remain in office while the Assembly members and the President are elected. However, for many, this difference is minimal since, in practice, both presidents will remain in office without a legislature to counterbalance them.

Motions of no Confidence

Both President Pedro Castillo and President Guillermo Lasso are undergoing an investigation process for alleged cases of corruption. The Ecuadorian president even had to appear on Tuesday to defend himself against the process initiated by the opposition parties that were the majority. For his part, Castillo does face investigations, not only within the legislature that sought his dismissal but also by the Prosecutor's Office, which conducted preliminary investigations.

Opposing Political Sides

One of the main differences between the two events is that both leaders represent opposite political camps. While Guillermo Lasso is a clearly right-wing politician, Castillo represents the values of the left. Neither can be described as moderate, and their positions made it difficult to reach agreements with other movements or parties.

Governing with Minorities in Congress

The most similar aspect in both cases is that the two presidents lack a legislative majority. Both the Peruvian and Ecuadorian Congresses were dominated by the opposition or fragmented between different parties, preventing the government from governing comfortably.

This is why both leaders also opted for the same measure. The legislative blockade did not allow them to develop their reforms comfortably, and this caused the friction between both branches of power to end up deepening the political and institutional crisis.

A Different Ending (For Now)

So far (Thursday, May 18), the fate of both leaders is different. On the one hand, Pedro Castillo is now in jail and branded as a coup plotter or dictator for trying to put an end to an organ of Peruvian democracy.

On the other hand, Lasso managed to dodge any attempt of retaliation and counts (apparently) with the support of the Military Forces. This could allow him to carry out his move, to govern during these months without a legislature, and then to run again in general elections where he will try to keep the presidency and, finally, control the majority of the legislature. The opposition also sees this move with some hope. Former president Rafael Correa said that the call for general elections opened the door for his movement to face Lasso again and, this time, to win the presidency.

Peru and a Crisis Continues

However, the most significant difference (so far) in both cases is the deep political and institutional crisis that Peru is experiencing. The case of Castillo being ousted and the attempted dissolution of Congress are not atypical in the nation. Something similar was shared with former President Martín Vizcarra; and his predecessor Pedro Pablo Kuczynski.

This shows that Peruvian institutions are already aware of this scenario and know how to act. For its part, this is the first time that Ecuador has experienced this case since the 2008 constitution came into force.