Colombia’s Environmental Shift: A 38-Year Retrospective

Colombia confronts a stark environmental reality, losing over half its glaciers since 1985, alongside a 4.4 million-hectare decrease in forest cover.

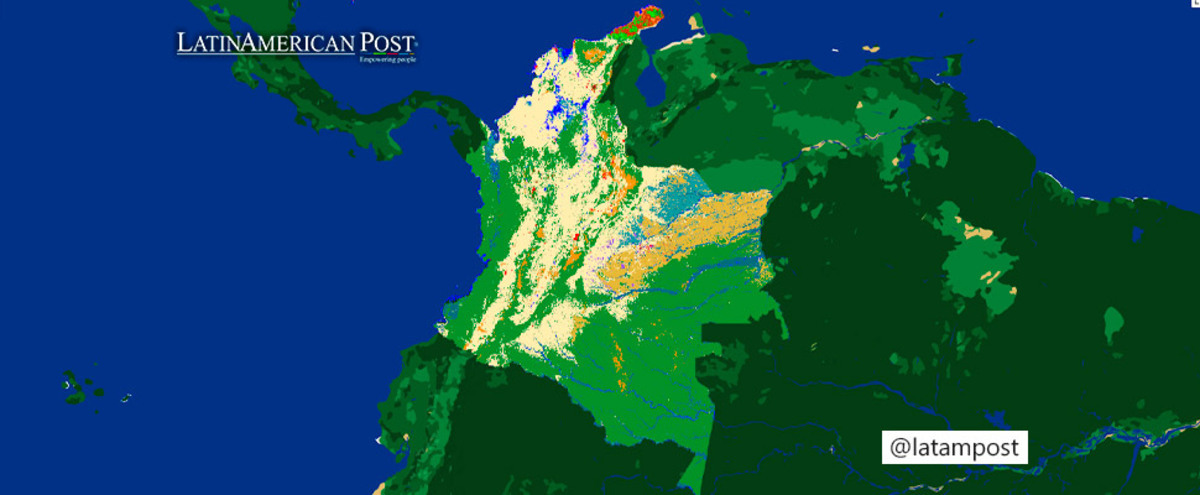

Photo: MapBiomas Colombia

The Latin American Post Staff

Escucha este artículo

Leer en español: El cambio ambiental de Colombia: una retrospectiva de 38 años

A 38-Year Environmental Odyssey

Colombia has witnessed a drastic transformation of its natural landscapes over the past 38 years, marked by significant environmental loss and change. This is the stark finding of MapBiomas Colombia, a groundbreaking tool unveiled in Bogotá that meticulously tracks the country's land cover and usage changes since 1985.

Developed by the Gaia Amazonas Foundation, a part of the RAISG and MapBiomas Network, this platform aims to revolutionize how data is gathered, stored, and analyzed, offering an unprecedented 38 annual maps of the nation's land use. Its creators anticipate that this extensive analysis will profoundly influence public policy, as the stark figures reveal significant reductions in natural covers and a rise in activities contributing to their decline.

MapBiomas Colombia distinguishes itself by leveraging artificial intelligence, which expedites the data processing to reveal four decades of land coverage in under a year. Adriana Rojas, the technical coordinator for MapBiomas Colombia-Gaia Foundation, highlights the platform's efficiency and comprehensive scope, which includes detailed thematic data and regional, municipal, and departmental analyses. It forms part of a South American network, facilitating cross-border environmental assessments.

The Grim Statistics: A Call to Action

The data presented by this tool paints a grim picture of climate change's impact: Colombia's natural vegetation has been reduced by 7.5%, and its forests have shrunk by 4.4 million hectares—an area more than twice the size of Bogotá. The statistics continue with a decline of 26.7 thousand hectares of floodable forests and a staggering 245.6% increase in mining activities. Palm oil cultivation has expanded by 349.4 thousand hectares, and aquaculture has seen an alarming rise of 1,857%, equivalent to 3,260 soccer fields.

These changes are not merely numbers but testimony to Colombia's shifting environmental tapestry. The glacier retreat is particularly telling, as glaciers are often called canaries in the coal mine for climate change. They reflect the broader global warming trends, with the withdrawal of these ice masses directly resulting from rising temperatures. The loss of forest cover has implications for biodiversity, water regulation, and carbon storage, raising concerns about the country's and the planet's health.

Deforestation's Global Impact: A Larger Narrative

Colombia's environmental alterations are part of a larger narrative of land-use change that has global consequences. Deforestation, in particular, contributes to greenhouse gas emissions and biodiversity loss. The causes of deforestation in Colombia are multifaceted, including illegal logging, agricultural expansion, and urbanization. These activities affect the land and the myriad of species that inhabit these ecosystems, including numerous endemic species that may not be found anywhere else on Earth.

The introduction of MapBiomas Colombia arrives at a critical juncture as the country seeks to balance economic development with environmental stewardship. The data underscores the urgency for sustainable practices and more vigorous enforcement of environmental protections. It also emphasizes the need for reforestation and conservation efforts that can help reverse some of the damage inflicted over the past few decades.

Colombia's joining Brazil, Bolivia, and Peru in the MapBioma initiative strengthens the regional commitment to environmental monitoring and protection. Venezuela and Ecuador are also poised to launch their versions by the year's end, signaling a collective move towards heightened environmental awareness and action in South America.

Also read: Regenerative Agriculture, Key to Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Empowering Decision-Makers: AI's Role in Environmental Conservation

The platform's scientific contribution must be balanced. Employing artificial intelligence offers a level of detail and speed that traditional methods cannot match, making it an invaluable asset for researchers, policymakers, and conservationists. With the ability to observe and analyze environmental trends over time, decision-makers are better equipped to create targeted policies that address various ecosystems' specific needs and challenges.

In sum, MapBiomas Colombia is more than a tool; it is a wake-up call and a guide for the future. It lays bare the environmental costs of unchecked development and presents a clear mandate for Colombia and its South American neighbors to forge a path of sustainable progress. The platform's insights invite us to act decisively, ensuring that the next 38 years tell a story of recovery and resilience for Colombia's precious natural heritage.